Yes, that is the question that I find myself answering today. I’ve never actually had someone ask me that or even argue about it with me, but while I was researching Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn’s 1535 royal progress I came across an article that put forward the theory that Mark Smeaton fathered the baby that Anne Boleyn miscarried on 29th January 1536.

Yes, that is the question that I find myself answering today. I’ve never actually had someone ask me that or even argue about it with me, but while I was researching Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn’s 1535 royal progress I came across an article that put forward the theory that Mark Smeaton fathered the baby that Anne Boleyn miscarried on 29th January 1536.

You can read the article yourself online – click here – but I’ll outline the key points that its author, Dr Brian M. Collins, makes in it and then share with you why I disagree with his theory.

In his article, Dr Collins explains that he bases his theory on three “surviving facts”:

- That Anne Boleyn miscarried a male foetus of about 15 weeks on 29th January 1536 and so “would have conceived around the end of September 1535 and hence probably while she was in Winchester.”

- That Anne confessed to Sir William Kingston when she was imprisoned in the Tower of London in May 1536 “that Mark Smeaton had visited her in her chamber while she was in Winchester and her ‘lodgings were above the King’s’.”

- That Mark Smeaton was the only one of the men arrested in May 1536 that confessed to sleeping with the queen.

So, the theory boils down to the conception date, the fact that Smeaton visited her chamber around that date and the fact that Smeaton confessed. Hmmm…

Let me take each of these “facts” in turn:

The dating of Anne Boleyn’s 1536 pregnancy

We know that Queen Anne Boleyn suffered a miscarriage on 29th January 1536, the same day that Catherine of Aragon was buried at Peterborough Abbey. Eustace Chapuys, the imperial ambassador, recorded that Anne lost “a male child which she had not borne 3½ months” and chronicler Charles Wriothesley corroborated this, writing: “Queene Anne was brought a bedd and delivered of a man chield, as it was said, afore her tyme, for she said that she had reckoned herself at that tyme but fiftene weekes gonne with chield […]” So, the primary sources tell us that Anne miscarried a baby at the 14/15 week mark.

But what did this mean back then?

Today, we date pregnancies from the first day of the woman’s last period. If Anne was 15 weeks pregnant when she lost her baby then by today’s standards, her last period would have started on 16th October. If we go with Chapuys saying 3½ months (14 weeks) then her last period would have started around 23rd October. If a woman’s average menstrual cycle is around 28 days in length, then she would, on average, ovulate around day 14. The fertile window is said to be 6 days leading up to and including the day of ovulation, but according to yourfertility.org.au: “The three days leading up to and including ovulation are the most fertile” and it goes on to explain that “depending on your cycle length the most fertile days in the cycle varies: If you have 28 days between periods ovulation typically happens on day 14, and the most fertile days are days 12, 13, and 14.”

Let’s assume that Anne was an average woman with a 28-day cycle. Her most fertile days would have been 27th, 28th and 29th October if her last period had started on 16th October, or 3rd, 4th and 5th November if she’d started her last period on 23rd October. According to records of the 1535 royal progress, Anne and Henry arrived back at Windsor Castle on 25th October, having visited Winchester in mid-September. So, the royal couple were back from progress when Anne conceived.

However, that’s all based on how we date pregnancies today. Were things different in Tudor times?

I asked historians Toni Mount and Amy Licence about it. Toni told me that there was no real understanding of gestation at this time and that a measurement of pregnancy “would only be certain from the first movement of the baby (i.e. when noticed by the mother)” or by signs that the woman would recognise, like morning sickness, for example. Amy Licence noted that Anne “was watching every month in hope” at this point and so may have “been counting the days after when she was due” her period, whereas another woman would have calculated it from the quickening of the baby. Amy also suggested that Anne might have been counting retrospectively, in that she’d missed a period or two, and then would be “thinking back to when they slept together and assuming 1 week or 2 weeks already.” As Amy also explained, they thought women should know the moment of conception by various physical reactions, so if she had an org*sm she’d have chosen that occasion. If not, she’d pick the time that she thought she’d felt the seed!”

This makes the 3½ months/15 weeks dating of Anne Boleyn’s pregnancy very speculative. Did Anne count 15 weeks from the time that she thought she’d conceived? Did she date it from the first symptoms of pregnancy or even from feeling the baby move for the first time? It’s impossible to say.

This makes the 3½ months/15 weeks dating of Anne Boleyn’s pregnancy very speculative. Did Anne count 15 weeks from the time that she thought she’d conceived? Did she date it from the first symptoms of pregnancy or even from feeling the baby move for the first time? It’s impossible to say.

If it was a case of Anne simply counting back to the moment she thought she’d conceived, that would take us back to around 16th-23rd October (14-15 weeks back from 29th January). Anne and Henry arrived at the Vyne in Hampshire on 15th October and then on 19th October moved on to Basing House, and on 21st to Bramshill and on 22nd to Easthampstead, before making their way back to Windsor Castle. They were not in Winchester at this time.

If Anne had counted from the quickening of her baby, which can happen as early as 13-16 weeks, then she would actually have been around 28 weeks pregnant when she miscarried, meaning that the baby was conceived at the end of July or beginning of August when the couple were in Gloucestershire. If Anne counted from a sign like morning sickness, which tends to start around the sixth week of pregnancy, then she would have been about 20/21 weeks pregnant when she miscarried, dating conception to around mid-September when the royal couple were in Winchester and Bishops Waltham.

Confused yet?

Does the fact that Chapuys and Wriothesley mention the baby being a boy give us any clue?

Well, no, not really. If Anne suffered an early miscarriage, say before 11 weeks, then the genital area would have looked very similar in both sexes, and a girl may well have been mistaken for a boy due to the genital “bud” at this stage.

Although Dr Collins writes “if we assume that medieval women counted their pregnancy to have started from the day they missed their menstruation, then to calculate the date of conception, two weeks should be added to the 15 weeks stated by Anne when she miscarried on 29 January 1536. Thus conception would have occurred in a two week period either side of 2 October 1535”, we cannot actually assume that at all. In her book Maids, Wives, Widows: Exploring Early Modern Woman’s Lives 1540-1714, Dr Sara Read quotes from 17th-century midwife Jane Sharp:

“Young women especially of their first child are so ignorant commonly that they cannot tell whether they have conceived or not, and not one of twenty almost keeps a just account, else they would be better provided against the time of their lying-in, and not so suddenly be surprised as many of them are.”

And Sharp was writing over a hundred years after Anne Boleyn’s lifetime. Sharp goes on to describe the “common rules” physicians have laid down “whereby to know when a woman has conceived with child”:

- “First, if when the seed is cast into the womb she feel the womb shut close and a shivering or trembling to run through every part of her body, that is by reason of the heat that draws inward to keep the conception and so leaves the outward parts cold and chill.”

- Secondly, the pleasure she takes at that time is extraordinary, and the man’s seed comes not forth again, for the womb closely embraces it and will shut as fast as possibly may be.

- Her belly becomes flatter because the “the womb sinks down to cherish the seed.

- She feels pain in her lower belly and around her navel.

- She suffers “with belchings”, goes off meat and feels weak in the stomach.

- Her periods stop unexpectedly.

- She has cravings for something that is not fit to eat or drink, “as some women with child have longed to bite off a piece of their husband’s buttocks.” (Anyone else had that happen?)

- Swollen, hard and tender breasts.

- Decrease in libido and sudden changes in emotions.

- Lack of interest in food and a tendency to vomit.

- Reddened nipples and enlarged veins in the breasts.

- The veins in her eyes become more obvious.

- Pain when having a bowel movement.

- Feeling weaker and a change in face colour.

And then a woman can also perform a 16th century pregnancy test to check, i.e. leave her urine to stand for three days before straining it through fine linen to see live worms in it (if she’s pregnant) or putting a needle in her urine for 24 hours to see if it goes black or dark coloured (not pregnant) or whether it has red spots (pregnant).

So, if Anne missed her period and had some of these signs, she might simply have counted back to the time she last had an org*sm with Henry VIII.

With all the uncertainty regarding how Anne would have dated her pregnancy, and even where Chapuys and Wriothesley got their information from, I do not believe that it is possible to give a date, or therefore a location, for the conception of Anne Boleyn’s baby.

Mark Smeaton visited Anne Boleyn’s chamber

Dr Collins quotes from Sir William Kingston’s letter to Thomas Cromwell “on Queen Anne’s behaviour in prison” which is damaged and undated. The ladies attending Anne in the Tower of London fed back everything the queen said to Kingston, who was the Constable of the Tower and whose job it was to report back to Cromwell. Here is the bit about Smeaton and Winchester, with the bracketed parts having been filled in by Samuel Weller Singer, the 19th-century editor of George Cavendish’s The Life of Wolsey, in whose appendices the letters appear. Singer explains that the parts he filled in are authentic as they are based on John Strype’s work and Strype saw the original letters before they were damaged in the fire of 1731:

“And then sayd [Mrs. Stoner, Marke] ys the worst cheryssht of heny m[an in the howse, for he] wayres yernes, she sayd that was [because he was no] gentleman. Bot he wase never in m[y chambr but at Winchestr, and] ther she sent for hym to ple[y on the virginals, for there my] logyng was [above the kings]….”

Anne appears to be saying that Smeaton had been to her chamber, which was above that of the king, at Winchester and that she had sent for him to play the virginals for her. Collins writes:

“Anne clearly wanted to acknowledge that Mark Smeaton had been in her chamber, though only to play music. However, why did she need to say that her lodgings were above the King’s? Was it to emphasise that she was living very close to the King and therefore could not have been ‘intimate’ with Mark Smeaton? Was it to counter the later confession of Mark Smeaton that he had been ‘intimate’ with Anne? Or, more likely, was it to counter any possible revelations at her trial by the ladies of her chamber who could have witnessed Mark Smeaton entering her chamber? Unless further evidence is forthcoming we shall never know for certain. Nevertheless, Anne does acknowledge that he was in her chamber and that fact has never before been linked with her pregnancy […]”

Isn’t it quite a leap to suggest that Smeaton being in Anne’s chamber at Winchester to play the virginals was a cover for Anne and Smeaton to sleep together? Yes, I believe so, particularly when we know that a queen never slept alone and that one of her ladies would have slept on a pallet in her room.

Even the indictments drawn up by the grand juries in May 1536 do not accuse Anne of sleeping with Mark in Winchester in September 1535. The dates and locations they give are 12th and 19th May 1534 at Greenwich and 26th April 1535 at Westminster.

Mark Smeaton was the only man to confess to sleeping with Anne

Dr Collins backs up his theory regarding Smeaton and Anne sleeping together at Winchester (at the Old Bishop’s Palace of Wolvesey Castle) with “confessions and allegations”. He points out that Smeaton was the only man to confess to sleeping with Queen Anne and this is true. Sir Edward Baynton, Anne Boleyn’s vice-chamberlain, wrote to Sir William Fitzwilliam, treasurer of the household, informing him that “noman will confesse any thynge agaynst her, but allonly Marke of any actuell thynge”. However, Anne Boleyn denied sleeping with the musician, she swore twice on the sacrament that she had been faithful to her husband, and the majority of historians believe her.

There are various theories regarding why Smeaton would make a false confession, including the claim that he was tortured or the idea that he was offered a more merciful death if he did. Anne Boleyn was shocked to hear that Smeaton had not taken the opportunity to retract his confession at his execution on 17th May 1536, saying: “Has he not then cleared me of the public infamy he has brought me to? Alas, I fear his soul suffers for it, and that he is now punished for his false accusations!” In his poem about the executions of the men, Thomas Wyatt, who knew Smeaton, described him as “A rotten twig upon so high a tree”, was this due to his false confession? It’s impossible to say.

The allegations Dr Collins writes about are accounts, such as letters from ambassadors at the court of Henry VIII, regarding news of Smeaton’s confession and the charges laid against the queen. None of these accounts, in my opinion, constitute evidence of an affair, they are simply reports of what was going on in May 1536, what was being said about Anne.

Dr Collins concludes his article with the following:

“It is left to the reader to decide as to whether Anne Boleyn and Mark Smeaton really did commit adultery in Winchester. The evidence is circumstantial but does fit the hypothesis; let us hope that more definitive contemporary accounts are hidden in an archive waiting to be discovered and able to prove or disprove it.”

I don’t agree that the evidence is even circumstantial. There’s no getting around the fact that Smeaton confessed to sleeping with Anne, but Anne denied it and nobody claimed in 1536 that Smeaton was the father of Anne’s dead baby or that he’d slept with the queen on the royal progress. Dating the conception of Anne’s baby is impossible and therefore it’s impossible to suggest a location. Isn’t it more likely that the father of Anne’s baby was the king seeing as the couple were desperate to have a son? So, no, the evidence doesn’t fit the hypothesis and there are too many ifs and buts for me to take this theory seriously.

I would, however, like to applaud Dr Collins on his research. Putting his claim about Smeaton and Anne Boleyn to one side, the rest of his article is excellent because he has pieced together the real itinerary of the 1535 progress – it changed from the proposed one outlined in Letters & Papers – and even gives details of the daily expenditure and how many miles the royal court travelled each day. Collins also list all his sources. The article is a wonderful resource on the progress, I just cannot agree with his hypothesis.

Please do have a read of Dr Collins’ article and then share your thoughts. Perhaps you disagree with me or you want to raise a point that I have missed, or perhaps you know more about pregnancy in the Tudor period. Please do share.

Notes and Sources

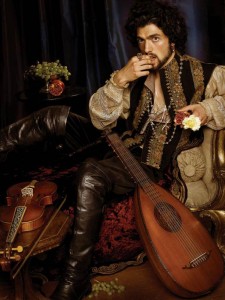

Pictures: Mark Smeaton, played by David Alplay, in “The Tudors” series, Showtime. Portrait of Anne Boleyn, unknown artist, National Portrait Gallery. Photo of Wolvesey Castle “Looking across the ruins of the East Hall, towards Wymond’s Tower” © Copyright Peter Trimming and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence, Geograph.org.

Sources:

- The Royal Progress and Anne Boleyn’s Visit to Winchester in 1535, Dr Brian M Collins, 09 November 2011, published at https://www.winchester-cathedral.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/The-Reformation-and-St-Swithuns-Priory-The-Royal-Progress-and-Anne-Boleyns-Visit-to-Winchester-in-1535.pdf

- Chapuys’ letter, Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 10, January-June 1536, 282.

- Wriothesley, Charles, A chronicle of England during the reigns of the Tudors, from A.D. 1485 to 1559, p33.

- “Women’s guide to getting the timing right”, published at http://yourfertility.org.au/for-women/timing-and-conception/

- Correspondence with historians Toni Mount and Amy Licence.

- Fetal Development, at http://www.baby2see.com/gender/external_genitals.html

- Miscarried at 13 weeks, photos of baby Nathan prove the humanity of the preborn at http://liveactionnews.org/finding-life-death-nathans-story/ – Do not visit unless you are ok with seeing images of a miscarried baby.

- Read, Dr Sara (2015) Maids, Wives, Widows: Exploring Early Modern Woman’s Lives 1540-1714, Pen and Sword.

- ed. Singer, Samuel Weller (1827) The Life of Cardinal Wolsey by George Cavendish, His Gentleman Usher, with Notes and Other Illustrations, Second Edition, p. 454-5.

- Sir Edward Bayntun’s letter, L&P x. 799.

- Anne Boleyn’s words about Smeaton and his execution, L&P x. 1036.

- Wyatt’s words on Smeaton are from his poem “In Mourning Wise Since Daily I Increase”.

- The indictments drawn up on 10th and 11th May 1536 by the Middlesex and Kent grand juries can be read in L&P x. 876.

- Sharp, Jane The midwives book, or, The whole art of midwifry discovered – parts of this are available online, e.g. at http://www.laphamsquarterly.org/flesh/what-expect-when-youre-expecting or you can read the reprinted Oxford Univeristy Press version of it edited by Elaine Hobby (1999).

Excellent piece of historical analysis.

Thank you, that’s so kind of you to say.

Fantastic analysis Claire! This is why I love this page: you share interesting things, analyse them and let us share our own opinions. Thanks!

Great article Claire. I think it’s an interesting theory put forward by Dr Collins, and we should always be open to new ideas about controversial personalities like Anne Boleyn. Whether or not Mark Smeaton was tortured, I do not believe he committed adultery with Anne and I have no doubt that the father of the miscarried foetus was Henry VIII.

It’s an interesting theory and the latter part of the article is excellent, but I just don’t think the “evidence” Dr Collins uses is actually evidence.

Claire, the idea that Anne would dare risk such an encounter is so unlikely. The fear of discovery, charge of treason & very possible execution would be a strong deterrent! They were at that time desperately trying for a male heir. Smeaton being tortured cannnot be dismissed. I would probably admit anything put before me in such a case. Why he did not retract in his last minutes of life I can’t answer. Perhaps a fear that the promise of a quick death might be withdrawn?

Anne was supposed to have said that she had never been unfaithful with her body which is an admission of some kind of affection toward someone at least..

That’s very much twisting Anne’s words. She was accused of offending him with her body, i.e. committing adultery, so her words in her confession on the Eucharist were answering that charge: “I solemnly swear on the damnation of my soul that I have never been unfaithful to my lord and husband nor ever offended with my body against him”. It’s a huge leap to say that because she didn’t mention her heart/mind that she had feelings for another man. Anne knew her Bible and would have known that it was considered adultery for her to covet another man, so when she says “I have never been unfaithful”, she would mean in any way whatsoever.

It is an interesting theory although personally I do doubt that it’s true.I have always wondered what made Mary I say that Elizabeth I had the look of Mark Smeaton about her.Did she have some private info regarding Elizabeth’s conception or was it simply fear and or something else?

I believe that Mary was having a dig at her stepmother, as she blamed Anne for her own maltreatment and the treatment of her mother. She later grew fond of Elizabeth, but she did refer to her as illegitimate from time to time as she saw Anne as her father’s mistress. She only found out that Henry was also behind her maltreatment after Anne died and it continued.

I think the chances of Mary knowing Mark Smeaton were incredibly low given how little time she spent at court during her teens.

I doubt he would be known to her by name. There most probably would be a “oh yes..that guy with the X” if she knew his name.

Unless of course, she had at one time had a crush on him.

HI. While I love interesting theories, one part of the thesis is not supportive. You cannot place any weight on a confession rung from torture. While I find it amazing that people can maintain the truth despite torture, pain changes your brain. Smeaton, not being noble, was certainly tortured, or at least told that his life was over, sign and be beheaded or get drawn and quartered. None of the nobles accused with Anne faced the worst punishment. I don’t even put much stock in the confessions given by Catherine Howard’s assumed paramours, besides the obvious, that Dereham knew Catherine before the marriage. One man, not even connected, but simply a friend had all his teeth pulled out. Dereham did not confess to adultery after marriage and was drawn and quartered. Confession and nobility are the key factors that got people a quick death. Being in a woman’s room does not mean that you had sex, and the fact that Anne let people see that he went in would imply no intent to commit adultery. Mary’s comment about Elizabeth was simply a low insult.

Firstly Claire, congratulations, this is a meticulous and impressive piece of research. Dr Collins makes an impressive and well thought out argument, his paper is praiseworthy, but as with Professor Bernard before him, he cannot prove his theory.

For one thing as your analysis points out the exact date of conception of Anne’s pregnancy cannot be accurately pin pointed for several reasons. We don’t know when Anne counted from, there was a lack of understanding, especially of early conception; there was no way to know how far along the unborn child was, the estimates of age are merely guesswork, not pinpoint accuracy, nor can the description of about three and a half months be entirely accurate. Anne, from your own analysis could have been anything from three to seven months pregnant and 15 weeks don’t place her at Winchester when she conceived.

Unlike Duchess Cecilly Neville of York, Henry was downstairs, not 100 miles away when a questionable pregnancy took place. Henry was within earshot of Anne and not to be too delicate, but had she been coupling away in a large wooden bed on creaking floor boards, with several lovers, or one lover on several occasions, as you would want to ensure conception, someone would have heard, that someone would even be the King. Anne was attended by a large flock of gossips, so why take the chance?

Anne and Henry spent many days hawking and hunting together and seem to have been on good terms, so why not just sleep with your husband?

Anne did say that Mark Smeaton was mooning after her, but she rebuked him as a low person, who should not speak to her. Playing music for the Queen on her command was a far cry from sleeping with her. Royalty and nobles had apartments provided the equivalent to a presidential suit, with several rooms so her chamber does not indicate her bedroom, which she shared with her trusted chaperones. She was making sure everyone knew that she would not dare do such a thing with her husband close by. Anne was protecting herself from the spies in her room in the Tower.

As Anne was never alone, her ladies were never implicated in bringing a lover to her room. Remember, Katharine Howard had to actively employ the aid of Jane Rochford and other ladies to be alone with Culpeper. I agree, such a dangerous sexual encounter would soon have started tongues wagging.

As for poor Mark Smeaton confessing, he may have been tortured, he may have had a fantasy, he may have been tricked by the promise of his life, he may have wanted revenge as Anne barely noticed him. There is room for speculation, but it does not prove he was the father of Anne’s lost son. Henry Norris, George Boleyn and even Thomas Wyatt have all been candidates for being the father of Anne’s babies according to popular fiction writers. Although the paper by Dr Collins is interesting and a wonderful piece of work. well worth studying, it is not compelling, nor does it prove this question.

Thanks for this excellent research and links. Enjoyed.

Bandit Queen makes an excellent point and I think this is something that some historians forget. No woman was charged with Queen Anne for aiding and abetting her illicit meetings with the king’s attendants. When Katherine Howard was accused of not being a virgin in the autumn of 1541, her attendant Lady Rochford was implicated with her and was said to have arranged Katherine’s meetings with Thomas Culpeper. Katherine informed her interrogators that Lady Rochford had acted in the role of chaperone. As is well known, both the queen and Lady Rochford were executed.

The argument that Anne was guilty as charged, even with just one of the five men who died with her, falls down on this simple fact. Why were none of her ladies accused of arranging her adulterous liaisons? Someone had to watch the door, make sure the other women were kept busy and did not suspect what was going on. Someone had to arrange the meeting places and make sure the king did not come upon them unawares. Anne’s ladies may have provided evidence against her – Warnicke thinks they testified about the nature of her miscarriage in 1536 – but they were not charged with anything.

Smeaton may have been tortured, equally his humble origins may have meant he was in a more vulnerable position than the other four men, one of whom was a viscount. In our modern times, we perhaps do not always appreciate the very real fear these individuals faced at the prospect of a horrifying death. Maybe Smeaton was promised a more merciful sentence, maybe he was tortured, maybe he said anything in his fear. But I look at Anne’s action of swearing her innocence upon the holy sacrament as significant. Even her enemies were not convinced she was guilty of the crimes she was charged with, although certainly many believed the execution was justice for her marriage to Henry VIII.

Thanks Conor, you are quite right, her ladies would have needed to be covering for her and the moment that Anne swore on the Holy Sacrament was moving and serious as it was believed that to lie under such a sacred oath was to put her immortal soul in grave danger. Anne had Kingston witness this and Cranmer tell everyone what she had said. Eustace Chapyus was no friend to Anne but even he did not believe the false charges. At least if I have to do any analysis on Anne in the future, there is a different point of view to refer to and the paper by Dr Collins is very well presented. Modern historians forget that it would have been very difficult for a Queen to sleep around, yet alone dangerous to put an illegitimate child on the throne.

We must also never forget Anne’s denial of the charges against her, shortly before her death, on pain of damnation, and swearing upon the Host. These days, we are so used to political figures fudging or outright lying (I’ll try not to digress with relevant examples), that it is hard for us to understand the 16th-century mindset, which saw eternal damnation as a true and ever-present danger. Anne would never have risked her soul by denying any charge that was true.

Let us also remember that Anne’s anecdote about Mark was told from the perspective of a member of the nobility commenting on the inferiority of a person of Smeaton’s rank. While this is not an attractive feature of 16th-century ideology, it is, again, hard to fathom why Anne would even consider (were it logistically possible, which it wouldn’t have been anyway) conceiving an heir to the throne with a person so far beneath her in birth. The fact that the anti-Protestant, anti-Boleyn forces came up with salacious tales of Smeaton being Anne’s personal equivalent of a marmalade jar should make us extremely wary of believing such propagandistic myths–myths like the Nicholas Sanders one about Anne’s supposed deformities.

I am left wondering whether English queens were ever in the habit of summoning musicians (male) to play for them in their bed-chamber? Is it possible that such a demand, bring the lad Smeaton to my chamber, would be considered, by her maids, as perfectly within socially acceptable norms, not worthy of remark or remembering? Can we ever imagine KofA, or Eliz.W, or any other queen, doing this? Because if it is at all unusual, or new, or not what one ought to do according to custom, then certainly some question arises, and I do not know personally what form this question takes, why ever anyone would do it. Given such a question, we have a pause. and that is all that is needed here. A pause.

I’m not sure that bedchamber was what Anne was referring to. When she mentions her encounter with Smeaton in her apartments in 1536, when he was mooning around, she spoke of her presence chamber and that was the room where a king or queen saw visitors. I expect that this would have been that chamber too. I’m sure it would have caused outrage and gossip if she’d called him to her bedchamber. A king and queen would always have been given a suite of rooms, and this was the Bishop’s Palace so there would have been room to do this.

Meticulous work on Doctor Collins’ part gathering the information, and excellent analysis Claire’s part. On the question of medieval calculation of pregnancy I wondered: can we get any clues from Elizabeth’s birth about how Anne would have counted 15 weeks of pregnancy? If we knew how Elizabeth’s due date was calculated it might tell us how far along “15 weeks” really was.

Thank you!

What’s interesting about Elizabeth’s birth is that Anne only took to her chamber on 26th August, less than two weeks before Elizabeth was born, rather than taking to her chamber 4-6 weeks before the birth. Was Elizabeth early? Did Anne enter confinement late, on purpose, to make it look like Elizabeth had been conceived legitimately? Did Anne just get her dates wrong? Lots of questions about that pregnancy too! So, unfortunately, it doesn’t help.

Great article. As always with Anne, we have a lot of information but not quite enough for a definitive answer. Tantalising and frustrating as ever. Desperate for a child? Possibly. Enough to sleep with a commoner if the chance arose. Why not? But we all know even then Anne inspired strong polarised opinions and emotions in others as she still does today but there seemed to be no contemporary rumours of affairs before the trial, unlike Catherine Howard where gossip was rife. Anne’s enemies were legion and even the sniff of impropriety with someone as lowly as Mark would have been enough ammunition to attack her outright. As everyone points out when and how could she be alone with him without someone knowing?

Most of the women who escaped Henry went on to conceive quite quickly. Even Catherine Parr at an age considered old at the time fell pregnant soon after marriage. For me the problem of infertility lay as much with Henry as his wives. As many think Anne suspected. Desperate enough to secure her faltering hold on power to try anything? I could believe it.

But don’t. Simply too difficult to hide. Fantastic stuff! Which is why we all love Anne and can’t get enough!

I’ve never heard that Catherine Parr became pregnant!

As a student of the medical variety, I’ve absolutely loved the attention to detail on pregnancy dating, budding etc, and it’s certainly made for one of my more interesting blog alerts!

I absolutely love anything there is to do with Anne Boleyn and her story. I find it fascinating and almost addictive. I do have to say that I agree with you Claire when it comes to this hypothesis of Mark Smeaton fathering Anne’s unborn child. I have always wondered what Smeaton’s agenda was in confessing to something that was certain death, but came to my own assumption that the torture just became too much to bear and he said what they were wanting to hear

I have always believed that the allegations that were brought against Anne were false, and only created so that King Henry VIII could void his marriage to Anne without having to have yet ANOTHER divorce. This would have been quite a scandal for him, considering the fact he put so much time and effort into divorcing Katherine and bringing Anne to the throne.

Execellent post about a subject thatmight have even brought up during Henry’s time. I understand Elizabeth’s half sister, Queen Mary Tudor, even once made the remark that Anne used to keep Smeaton in a cupboard in her chamber or chambers and call for “Sweetmeats” when she wanted his sexual services. I personally think that Henry was of course Elizabeth’s father. I understand why Mary would make the remark I posted above, since both Henry and Anne put both her and her mother, Catherine of Aragon through hell.

I think Smeaton was tortured to some extent, how much I don’t know.But in confessing to sleeping with the Queen, he hoped that they wouldn’t execute him, maybe just through him in prision for a number of years.

Thanks Claire for giving us such a thorough and thought provoking analysis.

Tina

This is a wonderful article and in fact iv often wondered if Anne did sleep with her musician not because she was driven by lust but just to get pregnant, she allegedly said the King couldn’t perform and there was the tragic history of his offsprings deaths with Katherine, she surely would have suspected if the fault could have lain with him and not his first wife, only one child had survived the princess Mary and she was not robust, Katherine came from a fertile family and although the 16 th century was known for its high mortality rate amongst the high born and lower classes to Anne could well have felt a genuine real fear that if Henry couldn’t father healthy children, she may never get pregnant and her position as queen would be decidedly shaky, it is not unfair of us to just assume maybe she did sleep with Smeaton just out of a fear to keep that position, Smeaton was young and robust, he could be silent on pain of death if they were discovered but was Anne reckless enough to do such a thing and she would have had to have the complete trust of any servant who was in her employ, if we can put ourselves in her shoes and try to imagine the scenario of Henry’s court 500 years ago, there was this great hot tempered King who was displeased with his wife, he was not enchanted with her as he had been and she had failed to give him a son, everywhere she looked there were enemies waiting to bring her down and there was the smug faced Jane Seymour who happened to be her husbands mistress, if she had a son she would have his undivided attention and he would never sought to replace her, if she had a son no matter whose it was, she would be safe, it was an awful situation to be in as there was a very high risk of danger as her tragic successor Catherine Howard, found to her cost yet did Anne actually do it, did she sleep with another man? There was her public oath on the sacrament that she had never deceived the King yet was that just a lie, I find it hard to believe she was lying as she was very religious, yet Norah Lofts says in her biography she could well have practised the dark arts and by lying on the sacrament, ensured her place with Satans handmaidens, and as usual with Satan she had been given everything and had it taken away, this oath she swore led to many historians believing she was innocent of the crime of adultery all except Bernard Shaw who thinks she could have slept with Norris as well, yet Norris was known to be a very decent man and a close friend of the King, one theory about Anne is she could well have been rhesus negative wich would explain her subsequent miscarriages after Elizabeth, she was possibly blaming Henry for the deaths of her babies and he was blaming her yet with any other man, had she that condition, she could never have carried another baby full term, as what happened with the death of her final infant.

Until reading this I was always under the impression that it was a fact that the unfortunate Mark was tortured. Also it seems likely that he was promised a less painful death for the confession and who could blame this poor soul. I have read that he was in love with Anne, also that he was probably gay,so torture and the threat of awful deaths seem the most likely reason for his confession. Also, Katherine suffered so many miscarriages and had one healthy birth is it not possible that the fault and reason for miscarriage and still birth lay with Henry? If so, if it is medically a sound supposition then it would seem much more likely the child was Henry’s.

I don’t believe Anne was guilty, but I do wonder who the lady staying in her chamber was?

Lady Rochford helped Katherine Howard sneak a lover into her rooms and it would have gone unnoticed if Katherine’s past hadn’t come back to haunt her opening an investigation into her behavior. Just a thought. Also Anne spoke to her brother and to Lady Rochford about the kings impotence and possibly the fear of not being able to produce an heir would have prompted Lady Rochford to assist in a lover visiting her chambers. If Anne did commit adultery, which I don’t believe she did, it would have been out of fear for her position and her life.

Why would she commit adultery out of fear for her life? That makes no sense at all. She would be jeopardizing everything by committing adultery and also if Henry was impotent, for which besides Anne’s moaning, we have no evidence, it would be more evident that he wasn’t the child’s father. It would be an incredibly stupid thing to do, there is no evidence for it and nobody was charged with helping her.

A different lady slept in the Queens bed chamber regularly on a rotation basis and why is poor Lady Rochford the fall guy here, yet again? She was the chief Lady in Katherine Howard’s household and as a senior, experienced woman, the most likely explanation is that Kathryn confided her loneliness and need for help to her and commanded her to assist her to see Thomas Culpeper. There is no way Anne committed adultery, although Dr Collins adds to the analysis.

why does james vi look so different from his parents. was david Rizzio his father?

Ann was by then in need of a child if Mark Smeaton did visit her would she in her royal hopes have had sex with her lute playing pop star. Maybe be she did. We shall never know. Was she a traitor no .She died because that evil monster had had enough of her.Not another reason can be pointed clearly at her on what was in that trail she was sentenced unjustly. So what of her bastard husband the Welsh son of a man who had stolen the throne as so much garbage. Henry V111 died and in Wndsor layng over night in the warehouse his body leaked fluids through the wood coffin floor and the dogs did come to lick it all up .This was the bibles story of the fate of that worse King to be born shalt be eaten of by dogs . Ann in death will never see him ever again, poor girl as he will be in another darker place

Utter rubbish .Anne swore before God she had never had sex outside marriage to Henry the odious toad . I cannot see a woman facing death lying just to save her reputation. This the work of another evil human called Cromwell who made it all fit in for death for Anne. My own blooded ancestor had it that Anne was framed and as he was there at time As Baron Kendal I expect he knew what he was talking about. Many try to make a bob or two knowing history but if as degree holder historian and lawyer Id say no record to say she was Marks lover exits in a court noted for gossip only at her trail was question raised and Henry even saw it a not right. Vain he was and danger even to himself I cant see him disagreeing with his man in front of belted Earls and all appointed if he believed Anne was Seaton lover. Why would a Queen stoop that far just for sex when she could have the lot if that way inclined. No evidence exists for trail on this subject so stop making waves