Our ‘Real Wolf Hall’ series of articles continues today with a wonderful article by Teri Fitzgerald on Gregory Cromwell, son of Thomas Cromwell. Make sure you read Teri’s article on Cromwell’s family from last week too – click here.

Gregory Cromwell (played by Tom Holland in Wolf Hall), was born to Thomas Cromwell, a successful London merchant and lawyer, and his wife Elizabeth Wykys, either during the closing weeks of 1519 or early 1520.1 A miscalculation of the boy’s age and an inaccurate estimation of his birth year (1515/16) by J. S. Brewer,2 subsequently accepted by James Gairdner (Dictionary of National Biography) and R. B. Merriman (Life and Letters of Thomas Cromwell) has resulted in persistent myths, not only about Gregory’s character and abilities, but also his relationship with his father.3

Thomas Cromwell was devoted to his son Gregory and took great pains over his care and education.4 His early instruction was supervised by Margaret Vernon, prioress of Little Marlow in Buckinghamshire, a close friend of the boy’s father, whose correspondence with him provides insight into the boy’s early life and places his birth in around 1520.5 From around 1528 to 1533, Gregory and several other boys, including his cousin Christopher Wellyfed and Nicholas Sadler, were at Cambridge. His tutors included John Chekyng, Fellow of Pembroke Hall, and Henry Lockwood, Master of Christ’s College. Henry Dowes, the son of a wealthy Maldon merchant, would later oversee his instruction in History, French, Latin, music and other subjects under a number of carefully chosen tutors, at the homes of his father’s friends and colleagues.6 Dowes would maintain his connection to his pupil for the rest of his life. The young man, praised by the Duke of Norfolk in 1536 as “a wise quick piece” spoke Latin and French, played the lute and virginals, was accomplished in horsemanship, skilled with a longbow and must have been quite a catch.

An approach by Sir Thomas Neville of Mereworth, Kent for a marriage between Gregory and his daughter and heir, Margaret was unsuccessful in 1535,7 but following Henry VIII’s marriage to Jane Seymour, Thomas Cromwell arranged a match between his son and the Queen’s widowed sister Elizabeth, Lady Ughtred.

Elizabeth was the daughter of Sir John Seymour of Wolf Hall, Wiltshire and widow of Sir Anthony Ughtred, governor of Jersey who had died in 1534.8 Gregory married Elizabeth on 3 August 1537 at Mortlake,9 in the same month that his father was made a Knight of the Garter. A portrait miniature by Hans Holbein in the royal collection in The Hague (Fig. 3) is quite likely to represent Cromwell’s son, Gregory, and may have been painted around the time of his marriage along with a portrait miniature of his father wearing the Garter collar. (Fig. 4)

In November, he and his cousin Richard participated in the funeral procession of the Queen, each carried a banner.

Early in 1538 Gregory and his wife arrived with a large retinue at Lewes priory in Sussex that had recently been acquired by his father. At Lewes, he was appointed as a justice of the peace and in in May of the same year the couple’s first child Henry was born. A second son, Edward, followed in 1539 and a third, Thomas, in 1540 as well as two daughters: Katherine in around 1541 and Frances about 1544.

After the appointment of his father as constable of Leeds castle Gregory and his growing family took up residence there in 1539. He was elected as one of the knights of the shire for Kent to the Parliament which commenced on 28 April that year, his partner, the lord warden of the Cinque Ports, Sir Thomas Cheyne, no doubt ensuring his return at his father’s request.

On 8 May he represented his father in the great London muster when three divisions, each of five thousand men and their attendants marched through the city to the Palace of Westminster where the king stood in his gatehouse. In December he travelled to Calais in the retinue of the Lord Admiral to welcome Anne of Cleves, whose marriage to the King would prove to be the catalyst for his father’s fall from power. In May 1540, as Lord Cromwell, following his father’s elevation as Earl of Essex, he participated in the week-long jousts at Westminster, which was also the scene of his father’s sudden arrest on 10 June. Whether or not Gregory was present in the Parliament when his father was attainted in unknown. A desperate letter written by his father to the king suggests that the he feared his son would go down with him:

“Sir, upon [my kne]es I most humbly beseech your most gracious Majesty [to be goo]d and gracious lord to my poor son, the good and virtu[ous lady his] wife, and their poor children.”

Gregory’s wife quickly reassured the malevolent monarch of their loyalty:

“Most humbly beseeching your majesty in the mean season mercifully to accept this my most obedient suit, and to extend your accustomed pity and gracious goodness towards my said poor husband and me, who never hath, nor, God willing, never shall offend your majesty, but continually pray for the prosperous estate of the same long time to remain and continue.”

Thomas Cromwell was beheaded on Tower Hill on 28 July, the day of the king’s marriage to fifth wife, Catherine Howard. The condemned minister’s estates did, indeed, revert to the crown but within a few months of his father’s death, on 18 December 1540, he was raised to the peerage as Baron Cromwell of Oakham. This was not a restoration of his father’s barony, but a new creation. The following February he received a royal grant of some of his father’s lands, including the site of the abbey of Launde, which would become his principal residence. Further royal grants followed during the reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI. He was made a Knight of the Bath at his nephew Edward VI’s coronation in February 1547.10

For reasons that remain unclear, Gregory did not hold a post at court and for the last ten years of his life he was involved in the management of his estates together with shire administration and was assiduous in attendance in the House of Lords. In 1542 and the following year he was present at about 80 per cent of the recorded sittings, and he made up for his absence in 1544 by attending on 25 out of 26 possible occasions in 1545, and in 1547 he was present at 166 out of a total of 174 sittings. He continued to accumulate property and by the time of his death in 1551, he was one of the wealthiest landowners in the Midlands. As brother-in-law to Henry VIII and Edward Seymour, and subsequently as uncle to Edward VI, Gregory used his influence to the benefit of his family and friends. He maintained close ties with his cousin Richard, Ralph Sadler and William Cecil, his “especial and singular good lord”. His grant of an exemption from serving in the French campaign of 1544 and absence from Parliament during that year suggests a serious illness or injury, however he appears to have fully recovered. His subsequent regular attendance of Parliament, the capable management of his estates and accumulation of wealth certainly dispel the myths about his health, character and ability.

The exquisite portrait of the unknown youth aged around sixteen painted in the mid-1530s (Fig. 3, 6) bears a striking resemblance to another unidentified Holbein portrait: that of a man aged 24, painted in 1543. (Fig. 5, 7) Both these portraits have long been associated with the merchants of the Steelyard in London, despite the fact that both sitters appear to have English features and are wearing English clothing. Most remarkably, their features also resemble those of Henry VIII’s right-hand man, Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex.11

There is little doubt that the two miniatures represent the same individual, the blue eyed youth depicted six years later having reached manhood. The portrait of the Man aged 24 was looted from the Danzig Museum (now the Gdansk National Museum) by the German occupation forces in 1943, then claimed by the Soviet Union’s Red Army as spoils of war in 1945. In 2013 it was listed as one of eighteen disputed works of art subject to restitution requests by the Polish government and located at the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow.12 13

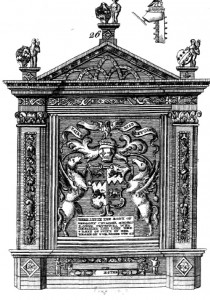

Gregory Cromwell died of sweating sickness at Launde Abbey on 4 July 1551 and on 7 July was buried in the chapel there.14 His magnificent tomb monument, which is to the left of the altar, has been described by Nikolaus Pevsner as “one of the purest monuments of the early Renaissance in England, very grand and restrained.”15 He was succeeded by his son Henry, a minor at his father’s death, who was first summoned to Parliament in 1563. Gregory’s widow married, in 1554, John Paulet, Lord St John, who succeeded his father as 2nd Marquess of Winchester in 1572. Elizabeth died 19 March 1568, and was buried 5 April16 in St. Mary’s Church, Basing, Hampshire.

The author wishes to thank Professor Diarmaid MacCulloch, whose astute observation appears to have unearthed Thomas Cromwell’s ‘treasure’. Diarmaid MacCulloch is Fellow of St. Cross College and Professor of the History of the Church, Oxford University. His next book is a biography of Thomas Cromwell.

Other ‘Real Wolf Hall’ articles:

- The Cromwell Family in Wolf Hall: Cromwell the Family Man

- The Real Wolf Hall – The Cromwell Family in Wolf Hall: Richard Cromwell

- Who was Walter Cromwell?

- Who was Thomas More?

- Wolf Hall: A Guide to Characters and Events

- Wolf Hall: The Real Cast

References

- M. C. Erler, Reading and writing during the Dissolution, Cambridge, 2013, pp. 94.; H. Ellis, Original letters, illustrative of English history, third series, 1846, vol. I, p. 338. ; T. Fitzgerald and D. MacCulloch. (2016) ‘Gregory Cromwell: Two Portrait Miniatures by Hans Holbein the Younger’, The Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 67(3), pp. 587–601. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022046915003322

- W. F. Hook, Lives of the Archbishops of Canterbury, vol. VI, London, 1868, p. 122.

- R. B. Merriman, Life and letters of Thomas Cromwell, vol. I, Oxford, 1902, pp. 53-4. ; D. Loades, Thomas Cromwell: Servant to Henry VIII, Stroud, 2013, pp. 17, 34–35, 82–83.

- Erler, pp. 88-106, app. 4, pp. 157-168.; Ellis, pp. 338-340, 341-5.

- Erler, p. 94.

- A. D. K. Hawkyard, “Cromwell, Gregory (by 1516-51), of Lewes, Suss.; Leeds Castle, Kent and Launde, Leics.,” The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509-1558, 1982.; Ellis, pp. 341-345.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Letters and papers, foreign and domestic, Henry VII, vol. xiv pt 2, 782.

- Hawkyard.

- T. Fitzgerald and D. MacCulloch.

- AFP, “Poland’s culture minister Bogdan Zdrojewski seeks return of art seized by Soviet Russia in 1945,” artdaily.org, 16 May 2013.

- BAT (PAP), “Polska chce od Rosji zwrotu 18 dzieł sztuki, Poland wants Russia to return 18 works of art,” Nowy Dziennik, Polish Daily News, 17 May 2013.

- Hawkyard.

- N. Pevsner, E. Williamson and G. K. Brandwood, The buildings of England: Leicestershire and Rutland, 2nd ed., 2003, p. 198.

- College of Arms, “Catalogue of the Arundel Manuscripts in the Library of the College of Arms,” p. 63, 1829.

He was a different man than his father. And I think that his father wanted it that way. The book “Wolf Hall ” is good fiction, because it makes us want to know more. And we get a different point of view. But characters personalities were sometimes seen through modern sensibilities. And history put aside for drama. Just didn’t get into it…

Hi Marie,

I loved the book because it took all the same evidence that anyone could look up, and then filled in the gaps between. She left some things out that definitely messed with the scales of fairness, but she did not put aside history for drama at all. Good lord, drama leaps off the page of even the dullest history book on the Tudors. it is baked in!!

IMO, Gregory Cromwell joins John More as grossly undervalued, simply because they failed to follow in the footsteps of their extraordinary fathers. I see them in the same “support group” as Thomas Winter (Wolsey’s illegitimate son); Edward VI is not included because his untimely death means we don’t know how he would have turned out.

I am always amazed at the level of detail in Hans Holbein’s portraits. Thanks to him, we are able to gaze on the faces of the Tudor court. The unknown youth and the man aged 24 definitely look very much alike!

Theflowerlady@btinternet.com

Just reading Hilary Mantel’s book featuring Thomas Cromwell and family , intrigued and interested to find out about Gregory and his life.Thank you.

Through Gregory, Thonas Cromwell is an ancestor of the Queen through her mother.

What would Henry say to that?

I am very excited to read Teri’s article. I wrote an article about Gregory Cromwell, as well, a year ago. I am very pleased that Teri agrees with me about his age. What my articles lacks, however, is the theory around the beautiful Holbeins that Teri believes to be Gregory. I knew there just had to be at least one out there, but which “unidentified” portraits. I have never seen these, and Teri’s evidence is quite compelling to say the least.

The Diarmaid MacCulloch Cromwell biography can’t come out fast enough for me! Great job Teri!

I have had Professor Diarmaid MacCulloch’s book “stripping the alters” on my fightable for a year now, for shame on me! I must start it immediately. As he has made some acute observations of Mr Cromwell. I truly look forward to reading his next book.

Great article. Thank you.

As a descendant of Gregory Cromwell through my grandmother (via the families of Drake of Buckland, Crymes and Trewelha) I am very interested in the question of the date of Gregory’s birth. Since we know that he was at Cambridge University in 1528, an age of 14 rather than 8 then would surely fit much better. 14 was the usual age for university education in Tudor England, which followed the completion of a period of private tuition. Also whilst some of her letters are actually dated, I see that the particular letter from Margaret Vernon to Thomas Cromwell which mentions Gregory’s education with her is undated and if it were dateable to 1528 why would she say Gregory was under her governance until the age of 12 when he had left her and as we know from John Chekys’ dated letter was at Cambridge that year? Margaret Vernon was Prioress of Little Marlow from at least 1521 and so the letter could have been written much earlier. Furthermore, the age of majority in the 16th century was 21, not 18, and if Gregory were born c 1520 he would still have been a minor when he was appointed both a JP and an MP. I am particularly interested in how these discrepancies might be overcome as there is possible alternative portraiture of Gregory to be identified if he was born at the earlier date of c 1514 rather than the revised date of c 1520. So comments on all of this are very welcome!

Kevin,

The Letters of Margaret Vernon and John Chekyng provide strong evidence that Gregory Cromwell was a young boy in 1528.

Margaret Vernon to Cromwell in 1528:

“Your son is in good health, and is a very good scholar, and can construe his paternoster and creed. When you next come to me I doubt not that you shall like him very well.”

Learning to translate the Paternoster and the Creed from Latin was an elementary exercise for young children.

In a later letter, Vernon was objecting to the fact that Gregory, who was still under the age of 12, had been removed from her care and sent to Cambridge:

“You promised that I should have the governance of the child till he was 12 years old. By that time he shall speak for himself if any wrong be offered him, for as yet he cannot, except by my maintenance…”

Vernon’s letter is one of a series that date to just before and after Wolsey’s fall.

Letters to Thomas Cromwell from Gregory’s Cambridge tutor, John Chekyng, describe a ‘little’ boy who ‘plays’ and who is learning to read and write:

July 1528/9:

“Gregory is not now at Cambridge, but in the country, where he works and plays alternately… He is now studying the things most conducive to the reading of authors, and spends the rest of the day in forming letters.”

and November 1528/9:

Little Gregory is becoming great in letters. (The editors of Letters and Papers dated these letters to 1528, but 1529 is more likely.)

Unbiased observers could come to only one conclusion, that the letters refer to a young boy, and not a teenager. Henry Ellis and Mary C. Erler have done so.

It was certainly not unheard of for minors to be elected to Parliament in the sixteenth century!

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=KpBxBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA224&lpg=PA224#v=onepage&q&f=false

https://archive.org/stream/electoratelegisl00walp#page/68/mode/2up

As I have mentioned in an exchange of messages online with Teri elsewhere, I think it highly unlikely that the portraits of the boy are of Gregory Cromwell. There is a problem with these portraits as regards both the ring the boy is wearing and the provenance. Here is my brother Andrew’s recent research regarding this. (Andrew is the head of the Old Master’s Picture department at Bonhams the London auction house):

“The first bust length tondo of the boy is in the collection of the Queen of the Netherlands (or is there a king now?) Provenance: Queen Sophie (1818-77), first wife of William II of Orange-Nassau and thence by descent. It doesn’t make any other comments.

The 1/2 length miniature is given as “a Member of the Steelyard Family (probably from the von Schwardzwaldt Family).” Provenance: Formerly Danzig Stadtmuseum, now missing after being looted in 1943. The identification is based on the fact that it was left in 1705 as part of the legacy of the patrician Danzig family, von Schwarzwaldt with a library and a coin collection to the Lutheran church of St Peter, Danzig. Rowlands says he is dressed in the English fashion. The ring he is wearing has the mark of the Danzig merchants, so he must have been a fully fledged member of the guild.”

I think the engraving of a portrait by George Perfect Harding which has been described as that of Gregory’s son Thomas the parliamentary diarist fits as a far, far better candidate for a lost portrait of Gregory since it clearly shows a man aged around 20 and (because of the fashion) has to date from c 1540, not c 1560 (thus cannot be Gregory’s son Thomas). This engraving (which subject to further research on this is no doubt that of a now lost portrait which in the early c19th hung at a seat of a descendant of the Cromwell family – and thus was identified as Thomas) would fit perfectly as Gregory – whether he was born c 1514 or c 1520. I intend to go to the Heinz Archive to make further checks regarding it.