On this day in history, 21st March 1556, the third of the Oxford Martyrs, Thomas Cranmer, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, leader of the English Reformation and ‘architect’ of the Book of Common Prayer, was burnt at the stake in Oxford.

On this day in history, 21st March 1556, the third of the Oxford Martyrs, Thomas Cranmer, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, leader of the English Reformation and ‘architect’ of the Book of Common Prayer, was burnt at the stake in Oxford.

Cranmer had been found guilty of heresy at a trial in September 1555 and in December 1555 Pope Paul IV had stripped him of his office of archbishop and given the secular authorities permission to sentence him. His good friends and fellow Oxford martyrs, Bishops Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley, had been burnt at the stake for heresy on 16th October 1555. The site of the burnings, which is in the middle of the road on Broad Street, just outside Balliol College, is marked with a cobblestone cross and there is a stone memorial, Martyrs’ Memorial, which can be seen at the south end of St Giles.

Martyrologist John Foxe wrote of Thomas Cranmer’s burning in his Book of Martyrs:

“With thoughts intent upon a far higher object than the empty threats of man, he reached the spot dyed with the blood of Ridley and Latimer. There he knelt for a short time in earnest devotion, and then arose, that he might undress and prepare for the fire. Two friars who had been parties in prevailing upon him to abjure, now endeavoured to draw him off again from the truth, but he was steadfast and immoveable in what he had just professed, and before publicly taught. A chain was provided to bind him to the stake, and after it had tightly encircled him, fire was put to the fuel, and the flames began soon to ascend. Then were the glorious sentiments of the martyr made manifest;—then it was, that stretching out his right hand, he held it unshrinkingly in the fire till it was burnt to a cinder, even before his body was injured, frequently exclaiming, “This unworthy right hand!” Apparently insensible of pain, with a countenance of venerable resignation, and eyes directed to Him for whose cause he suffered, he continued, like St. Stephen, to say, “Lord Jesus receive my spirit!” till the fury of the flames terminated his powers of utterance and existence. He closed a life of high sublunary elevation, of constant uneasiness, and of glorious martyrdom, on March 21, 1556.”

Trivia: Did you know that Thomas Boleyn acted as Thomas Cranmer’s patron from 1529 and that he lodged in Thomas Boleyn’s property, Durham Place, while he was working on the annulment of Henry VIII’s first marriage?

Click here to read more about Thomas Cranmer’s execution and what led to it, and you can read more about his life in Beth von Staats’s book Thomas Cranmer in a Nutshell and Diarmaid MacCulloch’s biography Thomas Cranmer: A Life.

Thomas Cranmer is a Tudor character that means a lot to me and you can read why in my article Me and Thomas Cranmer. I will be raising a glass to him today. RIP Thomas Cranmer.

You can also read more about Thomas Cranmer in the following articles:

- The Life of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

- Thomas Cranmer becomes Archbishop of Canterbury

- The Unlawful Execution of Thomas Cranmer

Notes and Sources

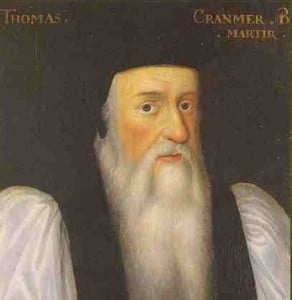

Pictures: Thomas Cranmer by an unknown artist; The Cross on Broad Street Oxford marking the place where Thomas Cranmer, Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley were burned at the stake. © Copyright Bill Nicholls and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence. Geograph.org.uk.; Martyrs’ Memorial, Oxford, 2005-03-17. Copyright © 2005 Kaihsu Tai, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, Wikipedia.

- Foxe, John, Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, Chapter on Archbishop Cranmer.

This was a terrible loss. Thomas Cranmer was a good honest man and one of the few of King Henry’s men who didn’t seem to be a toadie. I believe he always remained true to himself until the end. This of course got him condemned for heresy under Queen Mary. When he recanted (which I believe was the fear of an old man) he should have gotten a reprieve from the stake

I believe this was revenge by Mary for his presiding over the divorce of her parents.

I agree. This is so sad. I feel sorry for him.

clarification..from the stake but Mary did not grant him this and executed him anyway.

I find the execution of Cranmer very sad and iv always thought Mary had it in for him a bit because he had annulled her parents marriage, by now she had come to loathe those she called heretics and was hell bent on restoring Catholicism to England, fear of the fire had made him recant and this action had caused him deep shame, thus he cast his right hand in the flames and declared it should be the first to burn, as the flames lapped round him and the deadly smoke grew higher the wind must have caused the eyes of the horrified onlookers to close as the hot ash swirled around the sad company, the dreadful sound of the crackling of the wood and the pitiable prayers the victim was uttering shows all too harshly the awful suffering man can inflict on his own kind, and symbolises the horror of religious intolerance in the 16th century world, Cranmer’s death was unjustified as he had recanted and had accepted the teachings of the Catholic faith, he did this several times over yet Mary quite possibly thought he was not genuine and was just intent on saving his own skin, this very act shows her in a not too good light and I have always been sympathetic towards Mary yet I do abhor her lack of leniency towards Cranmer, he had served her father well yet had been a supporter of the Boleyns, that hated family whose one member had caused her mother much sorrow, because of that I do feel there was something personal in her attitude towards Cranmer yet the monarch in her should have overcome prejudice and realised he had only been doing what her father commanded, Cranmer was an old man and should not have suffered so, I believe that Mary’s reputation already becoming blacker throughout her reign suffered more because of this frail old man’s death, just as her fathers Henry V111 was stained with the blood of his two wives so I think Mary made a dreadful choice of action when she decided Thomas Cranmer Archbishop of Canterbury must die, RIP Thomas Cranmer, martyr of the Protestant faith.

I’m not sure what I think about Thomas Cranmer. While he was Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas More, John Fisher and the Carthusian monks of the London Charterhouse were all executed during his watch as metropolitan of Canterbury…what did he do to intercede on their bahalf? I don’t see any evidence of him doing anyhting at all. As a rerformer I don’t think Cranmer had any regard for anyone who adhered to the ‘old religion’ He must have found it difficult to celebrate the mass (which he would have done as a priest and bishop) during the reign of Henry while not really believing in the true presence in the eucharist. So his celebration of the mass would have been a farce?

Thomas Cranmer can be called the equivalent of Thomas More in the Anglican Tradition. Like More he was a scholar and a loyal and long standing royal servant and he is revered as a martyr and a man of integrity. Like More he was also ironically involved in the fight for orthodox teaching over heresy, condemning John Lambert for his views on the Eucharist, views he later adopted and Anitbaptism under Edward Vi, including an Anabaptist woman called Joan Broacher and his life was intertwined with the former in the divorce of Katherine of Aragon and the evolution of new learning. There are many parallels between the two men, who although on opposite sides of the divide between Catholic and Evangelical Christians of the sixteenth century, are rightly regarded as victims of the Reformation and martyrs.

It could be argued that Thomas Cranmer may have been also executed for treason and ironically the idea of the monarch as head of the Church was to blame. Mary, of course, unlike her father, didn’t believe that she was literally the Head of the Church as Henry did in the place of the Pope, but the concept that the Monarch made the policy by which all obeyed them and followed their faith was well established in the way people thought of their King or Queen at this time. In other words, Mary as with other Monarchs had been placed in charge of the country by the Divine Will of an All Powerful Deity and her laws and person were sacred. Henry Viii knew this even before the Act of Supremacy was passed and even with the restoration of the Catholic Church as it had been in 1529, with the much welcomed return to obedience to Rome and Reconciliation, there still remained the idea that Mary as Queen had the right to decide the faith of her people and what was right faith and what was not. Her religious policies incorporated the essential elements of a Supremacy, even if the actual title was dispensed with and the old belief restored. This made the style of Catholic belief and practice actually unique. Her Church was also more Evangelizing as there was a huge emphasis on teaching and preaching as well as authority. It was also viberant and enthusiastic in ways that had not been seen for several decades, with even elements of genuine reform and renewal. It was against this background that Cranmer found himself desperately trying to prevent the reversal of his own revolution.

He wrote a pamphlet which condemned the introduction of Mass and criticism of the new Queen was clear from the outset, but he then tried to reverse his stance. As an Evangelical, Thomas Cranmer, naturally didn’t want to see his hard work undone. He wad now devoted to the new Prayer Book and to reform and the English Scriptures and services, which is why he supported Queen Jane and hoped Mary would not succeed. He was originally tried for treason, found guilty and spared by the Queen, who could have had him executed, had she wanted revenge. Her motivation may have a personal element to it because Mary may well have blamed him for her parents divorce and even her mother’s death. Mary worshipped her father to the extent that even when faced with the stark reality that she could only return to Court if she totally submitted to him and others had worked to have Henry execute her, she still deflected the blame elsewhere. Mary long blamed Anne Boleyn, who yes, had a hand in her ill treatment, but it was her father who allowed it and continued it after Anne was executed. Mary still found it hard to accept. We have absolutely no evidence that Mary sought revenge on Cranmer or blamed him, but it would be very odd if she didn’t at least blame him unconsciously. However, she didn’t need a motivation. In his original opposition he was sticking to his convictions and his declaration for those who had kept Mary from the throne was treason without any other motives to try him. His beliefs, however, now came under scrutiny under the new laws on heretical teachings.

This is where there are contradictory elements in Thomas Cranmer, but they are entirely within his cautious character. His reform beliefs had evolved over time and while King Henry was alive he only revealed them slowly and he mostly conformed to the late King’s own peculiar brand of English Catholicism. Now for five years he had overseen many changes but the majority of people remained Catholic. He tried to accept the faith as proscribed by law and made a confession and declared he accepted the Catholic faith under Mary. We call this a recanting of his old beliefs. He was housed and imprisoned in various places in and around Oxford and there is a theory that he made his four statements of submission to gain more visitors, extra comforts, a bigger room, and so on and was conditioned to please his wardens. However, he was kept as a prisoner for some time so it is not surprising he would do so and agree to conform. Who can say we would not do the same? However, he did recant and he made a submission and he should have been spared again. However, when it came to his public submissions he took back his words and it was decided he was not sincere. As an unrepentant ‘heretic’ he was now unfortunately condemned and the law said there was one terrible sentence, burning at the stake. This cruel death was a terrible end for a man who had such a distinguished career. He was brave at the end and like many others of many persuasions, he stood up and gave his life for the witness of faith and the truth as he saw it. It could be argued that he was seen as the main mover in the reforms which Mary saw as dangerous and one of the charges was leading others into error. It is difficult to find the real motivation because there are so many, but I don’t believe Mary was being intentionally cruel, nor that she had some mental hang up from her own treatment. Mary was a woman of her time and her motivation was a strong belief that what was called heresy was a dangerous disease which had to be driven out. It was a normal thing to believe and Cranmer believed the same thing, but obviously what he accepted as true and heresy was different. There was not one reformed faith in England, but many, which is why we cannot speak of a Protestant faith at this time. It is also why even those of the Evangelical persuasion even condemned each other. I may accept Cranmer and others as martyrs but I can’t accept Mary’s motivation as revenge, not in a conscious sense, but as part of the tragic reality and natural conditioning that came from the fervent beliefs she and everyone else grew up with.

RIP Thomas Cranmer, another victim of the Reformation.

I see Cranmer’s execution as Mary Tudor’s vengeance come at last. Mary suffered greatly at the hands of Henry VIII, but Cranmer’s death reminded her subjects that she was indeed her father’s daughter.

But where is the evidence? What actual contemporary sources say she executed Thomas Cranmer out of revenge and not because he was the main person behind the reforms that Mary had to untangle? I am not saying she didn’t feel that way, but what evidence is there really? It’s all very well believing that as an interpretation or speculation, but if there is no evidence, then surely as historians there should not be a case made based on speculation.

I don’t think Jenn was stating it as fact, more as her view, and I think this view can be backed up, although we will never know for sure. Thomas Cranmer recanted five times and so he should have been absolved. However, although his execution was postponed, it was only postponed temporarily and then Mary set a date for it. As I say in my article from 2011 “Thomas Cranmer’s execution should never have happened, it was unlawful. Thomas Cranmer had obeyed Mary I and had recanted and repented of his Protestant beliefs. He had accepted the authority of his monarch and the Pope. Whatever he felt inside, he had signed his recantations and submitted to the Queen and Church”. I then list the possible reasons for his execution still going ahead: revenge, Cranmer as an example to others, politics and theology. Perhaps it was more to do with punishing him for being the leader of the English Reformation, but it certainly was not a lawful execution.

She wanted to get the ‘top man’, that’s a good point really as she wanted others to see it as a warning, still very very sad she could not find it in her heart to let him live.

Sorry, yes, I think I meant to post below, didn’t mean it to appear I was questioning Jen or her views. Oops, very odd day yesterday, so sorry about that.

I was wondering though that there seems to be more of a mixture of reasons rather than the personal ones Mary may have had, particularly as he was the top man, as Christine says, but I would just like more evidence about how she really felt and it appears absent. I did read this article, but I am still not convinced it was personal, especially as a more personal thing would have been to allow him to be executed for treason. One thing with a charge of heresy is that as Queen Mary can step back as it’s not a state process, but a religious one and one that gives someone the chance to repent. With Cranmer there are five or six times he does recant and his execution normally wouldn’t go ahead. There was a John Cheke who I think, from memory made a public recantation and was forgiven. The only reason I can think of why his execution still went ahead was his turnaround in public when they expected him to recant again and that Mary didn’t believe him. This is the only indication that the decision is personal, and it may well have been, probably was in fact, but is there actually evidence that Mary wanted revenge? I think we have to be careful when speculating unless we can say that there is evidence. I used to feel the same way but I changed my mind about a year ago as I couldn’t find direct evidence to support that Mary acted out of revenge. I see it more that he was the one who took the whole country down the path of what Mary and most other people saw as ‘heretical ‘ teachings and, although Edward Vi was actually behind many ideas, as were a number of the Council, Thomas Cranmer had the top Church job and introduced the main liturgical changes and someone had to take the blame. We know the circumstances in which the Archbishop found himself and in fact the process he went through was a long one because of new laws and the Church took over that process because of his importance and status. We also know he accepted the above but he may have done so in difficult circumstances and because of a need to please his captors. Of course, it really doesn’t matter, he recanted as many others did and his life should have been saved. Mary made a decision to allow his execution to go ahead. The question is why? Revenge would be a normal reaction, but I think it was more to do with his importance as the Archbishop who brought about the Reforms as much about his earlier connection to Mary and her parents divorce. I just don’t believe there is enough evidence to say it was out of personal revenge, but it was one of two factors.

I love your comment and could not agree more.

This is in reply to Jenn. It was all about vengeance.

I really wish I could edit replies.

Thank you. I agree that this was a very sad loss, however, as he was an old and frail man and he was an intellectual man as well. So many great minds were lost by execution because the authorities had an idea that they were right and everyone else was wrong, some young, some old, some women, some infirm, it did not matter, because the authorities were supposed to be influenced by a higher power. This wasn’t new either, it spread from the Ancient world to the 1800s across numerous cultures for many different reasons. So many lost people, so very sad.

I admit there is no contemporary evidence, that’s why I preface my statement with ‘I believe’. I also look at the emotional damage done to her by her father and the fact that she was a human being.

How were the mounds of ash disposed of? It is likely that identifiable bones were left, and these might have been treated as relics.

That’s a good question, after Thomas Becket was murdured his bones were seen as holy relics and people travelled to pray at his shrine for miracles, after Marie Antoinette was executed an old woman rushed forward to catch her blood in her handkerchief, it was believed the blood was divine and could cure sickness, I believe it happened at Anne Boleyns execution also, a fire would not destroy the human body completely, today at cremations the heat is so intense so as to destroy all the body, bones and teeth but a normal fire would not do that, however the funeral pyres they lit in Cranmers day must have been significantly large so as to dispose of a lot of the body, but there must have been some teeth left and an odd bone or two, I should imagine before anyone could descend on the poor victims remains they were searched by some gaurds and then buried, as the queen knew they would be kept by the sympathisers as holy relics.

That is actually a good question. Yes, bones of the executed, especially those of royal people or martyrs, were kept as relics. There is a collection of relics from several Catholic martyrs in Stoneycroft College in Lancashire for example and the last few people killed supporting Bonnie Prince Charlie and his father had pieces of hair collected by the Strickland family and kept at the Castle as relics. Thomas More had his head recovered and it is in the family vault behind a grill. Most people who were otherwise executed were buried in Saint Peter ad Vincular or All Hallows close to the Tower, but otherwise people claimed which parts they could and laid them to rest. I assume the bones that didn’t burn were claimed, but I really have no idea how the ash was removed or if the remaining bones could be claimed. That is a very interesting question. I wonder if they had a pit or if they disposed of the ashes. It’s horrible to think about. People being burned did have families the same as anyone so you might be right and any odd remains taken and buried with the ash before anyone could claim them. People at public beheadings would dip hankies into the blood, no matter who it was, because they saw a holy connection to the departed and people even combed the hair of heads, which is one of the reasons they put them up high on poles.

Hi BQ. I have a question regarding Thomas More’s head. Are you saying it is currently in the family vault? I knew that it was kept behind a grill but I thought I read somewhere that it disappeared sometime in the last 2-300 years.

Hi Michael it is generally known that Sir Thomas’s head was buried within the Roper family vault at St Dunstans church Cantebury, some say his daughter Margaret was buried with it and another source says that it was buried in Chelsea Old Church, Margaret outlived her father by nine years and I believe it was her dying wish to be buried with his head, it was at some time kept on vie behind a grille but I have no knowledge of the story that says it disappeared.

I think I may have a picture somewhere. It was placed originally in his daughter Margaret’s grave a couple of hundred years ago but was removed and placed in an alcove behind a grill. I last heard it was in Saint Dunstan still.

I think I may have a picture somewhere. It was placed originally in his daughter Margaret’s grave a couple of hundred years ago but was removed and placed in an alcove a grill. I last heard it was in Saint Dunstan still.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sir_Thomas_More_family%27s_vault_in_St_Dunstan%27s_Church_(Canterbury).jpg

My own image does not want to behave but there is a picture of the vault on Wikipedia and here is the link. I think the archaeology showed it was separated.

Imagine the gruesome sight yuk, all the flies buzzing round and the awful stench of decomposing flesh, the skin gradually rotting away till the skull becomes visible and the huge eye sockets like deep pits could be seen, I bet young lads on their way home from the taverns all fired up with ale would throw stones and old fruit at the heads, they probably had bets to see who could knock a head of the pole first.

http://www.roperld.com/RoperWilliam_MoreMargaret.htm

Here is a much better link to Saint Dunstan Canterbury about the vault, where the head and vault can be seen. The head was removed to the vault and it was sealed but there is a picture of the Roper vault and head and the chapel. It is only short but it gives the information.

The only two references of what happened to the ashes I can find are in Duffy who described the first burning of John Rodgers and states that some people who sympathetic to the victim gathered up the pieces of bone and ash in velvet clothes and kept them as relics. It was also noted that at this execution in London there was a demonstration. However, most were quiet and not all people were sympathetic either. There is not much information about what happened to the ashes but a recent account in the Guardian was talking about the DNA tests on ashes believed to be those of Joan of Arc burned by the English authority in 1415 in Rouen. The contemporary accounts say her remains were burned three times to reduce them to ashes as it was feared that she would be used as a symbol still for French rallying, which in fact her name was. Remains were found in a house that had been there known since 1858 and labelled as Joan but not much was known before this, but local legend said the family are descended from a pious French soldier who gathered her ashes and kept them. Some bone was found and a tooth. Now we can’t say of course it was Joan but the results of the DNA said the remaining human ash and bone is from the same female, a young adult female, possibly under twenty, but more than twelve years old and dated them to the early fifteenth century. If these few examples are anything to go on, it is quite possible that people present were allowed to collect the ashes before they were removed and buried by the authorities. It is not a question that appears to have a definitive answer, but burning was a punishment which was sadly part of many societies for many hundreds of years, originally being part of the way to prevent criminals having an after life in the Ancient world and for crimes of desecration or immoral acts. It was also seen as a cleansing fire which is one of the reasons it was used in the punishment of those in society who offended against the accepted divine order of the day, rather than another form of execution. It would seem incredibly cruel today and it was and we just cannot reconcile it with Christian or any other form of belief or even modern thinking, but it went on, not against heresy, but witchcraft in many cultures even into the nineteenth century. There must have been some proscribed manner of disposition of ashes and I suspect they were either gathered and placed in ground set aside or disposed of into the rivers because the condemned was excommunicated. One would hope the authorities allowed people to gather any remaining fragments and we probably are talking about fragments, first, out of compassion, but it was sadly, not always the case that local magistrates showed any compassion. It is a very difficult thing to talk about how humans behaved in such terrible ways towards their fellows and any reading on this subject, you really have to hold back the tears.

I was at a theoretical re-enactment of a real Victorian murder case last week and it was heart wrenching as it was in the actual courts and cells that the young man on trial was held. We the audience had to be the jury and decide his fate. Now, the young man was no saint and he and his gang were thugs, but we had to condemn an eighteen year old, unemployed Irishman to death if he was guilty. It was one of those incidents were a fight had taken place, in the poorest part of the city, a foreign sailor was killed and it was not certain which of the five men had killed him. The man in the dock had been singled out as the leader. Three others had been cleared, but they actually had blood on their clothes and this man didn’t. It later emerged that one of the others had confessed and he got away with it. The police also hid evidence that the sailor had a knife and was also no saint either. This sounded more like a fight than wilful murder. It also sounded more like our young man was innocent and was being made a scapegoat as there was a lot of crime and gangs and people in society were demanding an example and an end. The trial had some very political overtones. We found him not guilty because there was not enough evidence and we are obviously thinking about reasonable doubt. In reality he was hung and the hangman was drunk and it took eight minutes for him to die. The man who most likely committed the murder was on a ship to America the next day after he confessed to his cellmate but was then acquitted. Why? Because he had people who said his character was better, McLean had nobody. Political hunger and scapegoat fever, not justice won then and that has been the terrible truth of the centuries.

There may even have been a bit of that in the way Christian and earlier societies of various persuasions prosecuted those who had a different point of view, whom they saw as heretics, traitors, deviants, dangerous, a threat and not right. The clergy who were the main Church leaders under Edward were sought out first, probably as those responsible, those who were the least repentant and as those you could blame but they were also the ones who did stand their ground. Teaching and persuasive preaching and education were the first weapons to bring people back voluntarily and this to some extent was successful. Why the state was not persuaded to allow the recanted Cranmer to live is baffling, but I suspect his prominence had much to do with it. I just feel as many do that a way could have been found and Pole was normally persuasive in such cases, but this time he wasn’t. I think this is were Mary’s decision can appear personal, but I think there was more to it. Either way it is a very difficult thing to read and decide about and all of these men and women and young people are to be remembered with compassion and honour for their suffering. It was a cruel and terrible time and I don’t think we can ever understand it.

Hello BQ. Thank you for the interesting piece on Joan of Arc. I had read many years ago that her ashes were swept into the river to avoid them becoming relics. However, to put that into context I also read that Richard III’s remains were thrown into the River Soar, and that proved not to be the case.

Thank you BQ and Christine for that info on Thomas More’s head. I am glad it is in a safe place. I don’t think it would have been too gross. I’ve read that the heads of condemned traitors were parboiled before being displayed to preserve them. Still a nasty and distressing thought.

Sorry, only just saw this thread.

BQ is correct and here is another link with information about More’s head and what happened to it – http://www.lynsted-society.co.uk/Library/Books/Margaret_Roper_and_head_of_Sir_Thomas_More.html.

In 1978 the Roper family vault at St Dunstan’s was opened and the head was there. An article on this can be found at https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquaries-journal/article/roper-chantry-in-st-dunstans-church-canterbury/E0CC3EBC5C4E3CA73616BAB11EA6823A

His other remains were first buried at All Hallows and then moved to St Peter ad Vincula. I was able to visit the crypt at St Peter ad Vincula a few years ago and there is a memorial to him in there, although the exact location of his bones is not known.

Very interesting. I had previously read somewhere the account of Margaret Roper obtaining the head of her father from London Bridge but all of the other info is new to me. Thank you very much.

The last act of a devoted daughter may they rest in peace both of them.

I did a talk on Henry Grey’s head for the Tudor Society a few weeks ago because there is a legend that Frances Grey saved her husband’s head from the pike. The head was allegedly kept at the Church of the Holy Trinity, Minories, the church where the Greys worshipped. A head was indeed found there but it is not known whether it was indeed Grey’s.

That info on Henry Grey’s head actually came up on my Google feed a couple of weeks ago. There was also a photo purported to be his head.

Hello BQ. Thank you for the interesting piece on the ashes of Joan of Arc. I had read that they were swept into the river so that they could not be saved as relics, but then I also read that the remains of Richard III were thrown into the River Soar, and that proved not to be the case.

Hello Sheila and thanks for your comment, yes, it is very interesting to read the full story. The river seems an obvious place for ashes, although maybe they had some regulation about what went in there. The reason that people were burnt was considered merciful, as it was a foretaste of hell and they were given a chance to repent. Having said that it was also more practical as in the early days and in some other countries, drowning was used by both pre Christian society and some Christian societies but ceased as bodies in the river were found and later buried. As someone condemned was not reconciled to the Church, they would normally not be allowed burial in holy ground, so this was later stopped. This is the difference in our mindset and that of hundreds of years ago. It was a terrible way to die, but the main concern at the point of death was the salvation of the soul. It must have been a terrible sight and yet it was accepted and I don’t think we can ever really understand why. Where people just so used to such things or conditioned to see this as normal that few objected? Some resistance did occur, especially in London and especially when high profile people were burnt, but it was very sparsely spread and most executions had little more than a silent group of people, some sympathy was shown, but mostly silence. I find it horrible that anyone can watch an execution and not feel abhorrent at what they are witnessing. I hope some people felt it was wrong, but it was certainly not the case that it was unacceptable in the way we would be appalled today. It was a dangerous and terrible time and thank goodness it is not like that today. If we went back in time, it would be like going to Mars, totally alien and a struggle to survive.

I think you are right about not wanting people to save relics, but they saved some, it seems, especially if the heads of those beheaded is any indication or the bones from priests hung drawn and quartered. Yes, the stories about Richard iii certainly should tell us everything is not as it seems when it comes to tales of missing remains. The gentleman who wrote that to be fair went to the wrong place and the locals spun a good yarn. Graves in vaults were very rarely disturbed in the Dissolution, but tombs often did face some destruction, mostly from the period of the English Civil War. The fact that the Soar had actually silted up should have been a clue, but he apparently didn’t look. Fortunately the building covered the spot and we found him. There are many relics from those sad times, but it would be nice to think someone took care of the ashes. However, I think we have a better way to remember Thomas Cranmer and he gave it to us, himself, the Book of Common Prayer in the original form. I know it went through a few changes but it still retained much of what Cranmer intended. It is still one of the most beautiful of the English prayer books and is one of my favourites. Many of his works were preserved, so we have a legacy that is greater than any relic or tomb, his words.

Thank you also Christine and Michael for your comments and interest in the remains of Saint Thomas More. I hope the second link worked as the Wiki one was going wrong. Claire, thanks for the additional information and links. I have spent most of the day reading the update Thomas Cranmer. A Life by MacCulloch which of course is marvellous and brilliantly detailed and a scholars dream, but also very accessible for the popular reader, especially the last two chapters which chronicles his actions in the last few months of Edward Vi and his few months of freedom at the start of Mary’s reign and his long years of imprisonment, house arrest, living as a ‘guest’ but prisoner at the college and his back and forth state of mind to his final days. There are many books who bring out the humanity and the sometimes ferocity of Cranmer, especially when he did stand on his principles, such as his almost fiery contest with John Knox, but MacCulloch really does bring him alive and is highly recommended. I was sad to read on one of your many articles that some people see Cranmer as a coward because he gave in for so long, but he actually only gave in for a short time and was quite defiant when he was stripped of his office and priesthood and he was doing nothing different than many who conformed and who were reconciled to the Catholic Church. I see him as a human being, a frail human maybe due to his age and fear of the fires, but a normal human who at the end of the day, did what he believed was right and changed back to his own truth and I admire him for that. It was again a very sad and terrible end to a man of humanity and learning.

The link worked perfectly. Thank you.

You are welcome.

Your welcome Bq.