Thank you to historical novelist Judith Arnopp for stopping by The Anne Boleyn Files to share news of her latest book release and to tell us more about her writing. I loved Judith’s The Winchester Goose, so I’m looking forward to reading this one. Over to Judith…

Thank you to historical novelist Judith Arnopp for stopping by The Anne Boleyn Files to share news of her latest book release and to tell us more about her writing. I loved Judith’s The Winchester Goose, so I’m looking forward to reading this one. Over to Judith…

I’ve read about the Tudors since I was a teenager – a long time ago. I started off with Jean Plaidy, then consumed anything else I could get my hands on. When I first began to write professionally I set my books in the medieval/ Anglo Saxon period which is another era that I enjoy. The books did reasonably well but readers kept asking if I’d written any Tudor books, so in the end I obliged. That is when my readership began to expand. I owe my career to the Tudors.

Although there are a huge amount of books set in the period, and many different types: romance, fiction, literary fiction, readers never seem to tire of them. There is always a new generation who are unfamiliar with the Tudors. Most of us, at some point in our lives, go through a stage of fascination with Henry and his wives.

There is just something about the Tudors, whether it is the costumes, the politics, or the romance, they are never boring. There are so many avenues to follow, and new perspectives to take up. I am not mad-keen on revisionist history which is in danger of making everyone out to be a saint but I am keen on looking on events from a new perspective. Instead of the victim, become the abuser. It is a brilliant way of burrowing into their mind.

You have only to look at the success of Wolf Hall and Mantel’s unique presentation of Cromwell to see how this works. Usually he is depicted as a grim self-serving monster, reaping, without compunction, the victims that come between him and his all-consuming ambition. Mantel’s genius is to show the Tudor world through his eyes.

There are no thoroughly evil people, even the hardest criminals among us justify our actions. Cromwell was doing a job, a dirty job that few others could have done. In the end he was consumed by his own ruthlessness, destroyed by his own laws. In the last screen of the BBC production of Wolf Hall, when he is embraced by the increasingly manic king Henry VIII, the realisation of his own eventual end is written clearly in Cromwell’s eyes. And, for the first time (possibly) in history, and in literature, we have sympathy for him. That is the beauty of perspective, the joy of approaching a well-known subject in a fresh manner. It opens our eyes.

Tudor history, well, all history I suppose, is full of people yet to be treated in this way. Historical fiction is replete with stock figures, cardboard ‘monsters’ and plastic ‘saints.’ My hope is that Mantel will help writers of historical fiction to see the benefits of viewing these thigns afresh. I don’t mean whitewashing, I mean trying to understand and perhaps empathise.

It is something I always try to do in my own writing. There are negative characters, we need those for the sake of the plot, but I always try to provide a reason for their behaviour. No one is born ‘bad’; life experiences form our characters, and we never see ourselves as monstrous. When you study a character in depth, you will, in most instances, find possible motives buried away somewhere; an event that has altered their path and reshaped their opinions.

There are few characters in my novel A Song of Sixpence who are traditionally treated negatively. Margaret Beaufort, for one, is usually an ageing, overly pious, sometimes neurotic termagant but there is nothing to suggest this in the record. She was very religious, most people were, but there is no suggestion that she was unhinged. Devoted to her son Henry, she worked tirelessly and determinedly to put him on the throne. There is nothing wrong with that, she should be praised for it. I am sure we’d all fight tooth and nail for our children. I have some suspicion she may have been an interfering mother-in-law, we’ve all experienced those, but why do we always suppose her intentions were negative. Maybe her motives were born of affection and concern. The historical record suggests that she and Elizabeth of York were close so, in my novel, it is a slow burner; they start off at odds but end up as friends.

And then there is Henry VII. Traditionally we see him as a miser, the thief of another man’s throne, but he couldn’t have been all bad. He lived in harsh times. He saw the throne as his right – we all fight for what we see as our rights, don’t we? Once he was king he did a good job – when he died the coffers were comfortably full; he put down all the pretenders to his crown, and made numerous advantageous alliances. He also left an heir, Henry VIII. There is very little more required of a ‘good’ king.

And then there is Henry VII. Traditionally we see him as a miser, the thief of another man’s throne, but he couldn’t have been all bad. He lived in harsh times. He saw the throne as his right – we all fight for what we see as our rights, don’t we? Once he was king he did a good job – when he died the coffers were comfortably full; he put down all the pretenders to his crown, and made numerous advantageous alliances. He also left an heir, Henry VIII. There is very little more required of a ‘good’ king.

In my novel Henry is at first insecure, unsure of Elizabeth, and distrusting of his courtiers but in all likelihood, given what he’d witnessed of Richard III’s reign, he had good cause. He is quiet, calculating and wise. I’ve mixed negatives with a dollop of good intentions and, I hope, produced a more complex character to previous versions of Henry.

As for Elizabeth of York whose fictional representation is often rather meek, and sometimes cowed, I have tried to explore her character in even more depth. History presents her as a good queen, obedient and supportive of Henry VII. She took no part in the politics of Henry’s reign, but her charitable work is well recorded. She kept close to and cared for her sisters, and also had a direct hand in the upbringing and education of her younger children, keeping them close to her and teaching them their letters.

Prior to their marriage Henry and Elizabeth had fought on opposing teams. It is more than likely that there were some initial misgivings on both parts. A Song of Sixpence, written in the first person, provides insight into Elizabeth’s inner mind. She is determined to be a good queen, has ambition for her children, love for her country and fights to break down the barriers between her and Henry.

When Perkin Warbeck appears on the scene, claiming to be her brother, the younger of the two princes who disappeared from the Tower in 1483, her emotions are conflicted. She does not know if Warbeck’s claim is true. If he is indeed her brother, what will she do once Henry gets his hands on him? How will she stand by and watch her husband execute her brother? Yet, if he is her brother and he is victorious, she may have to witness him destroy her husband and steal the future of her sons. A complex situation with an unenviable mix of emotions.

When Perkin Warbeck appears on the scene, claiming to be her brother, the younger of the two princes who disappeared from the Tower in 1483, her emotions are conflicted. She does not know if Warbeck’s claim is true. If he is indeed her brother, what will she do once Henry gets his hands on him? How will she stand by and watch her husband execute her brother? Yet, if he is her brother and he is victorious, she may have to witness him destroy her husband and steal the future of her sons. A complex situation with an unenviable mix of emotions.

A Song of Sixpence is my fourth Tudor novel but there are plenty more to come. For my next project I am contemplating a trilogy of Margaret Beaufort’s long and eventful life. Then there is Margaret Pole, Katherine of Aragon, Jane Seymour and ultimately … when I pluck up sufficient courage … there is Henry VIII himself. The scope is endless, the prospect exciting, and my time in Tudor England far from over. I hope you will join me there.

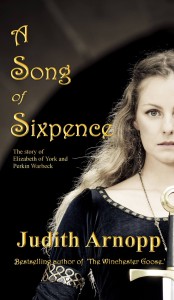

A Song of Sixpence is available now on Kindle and the paperback will follow shortly.

Book Details

In the years after Bosworth, a small boy is ripped from his rightful place as future king of England. Years later when he reappears to take back his throne, his sister Elizabeth, now Queen to the invading King, Henry Tudor, is torn between family loyalty and duty.

As the final struggle between the houses of York and Lancaster is played out, Elizabeth is torn by conflicting loyalty, terror and unexpected love.

Will Elizabeth support the man claiming to be her brother, or will she choose the king?

Set at the court of Henry VII A Song of Sixpence offers a new perspective on the early years of Tudor rule. Elizabeth of York, often viewed as a meek and uninspiring queen, emerges as a resilient woman whose strengths lay in endurance rather than resistance.

File Size: 2868 KB

Print Length: 348 pages

Sold by: Amazon Digital Services, Inc.

Language: English

ASIN: B00TUA5PTM

Available on Kindle from Amazon com – http://amzn.to/1AUOQQz, Amazon UK – http://amzn.to/1B50FSS and the other Amazon international sites.

For more information on Judith’s novels please visit:

Her webpage: www.juditharnopp.com

Her blog: http://juditharnoppnovelist.blogspot.co.uk/

Her facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Historical-fiction-by-Judith-Arnopp-/124828370880823?fref=ts

Her Amazon page: http://author.to/JudithArnoppbooks