As part of Anne Boleyn Day 2017, our commemoration of Anne Boleyn’s execution on this day in 1536, art historian and author Roland Hui is sharing an excerpt from his book The Turbulent Crown: The Story of the Tudor Queens about Anne’s execution.

As part of Anne Boleyn Day 2017, our commemoration of Anne Boleyn’s execution on this day in 1536, art historian and author Roland Hui is sharing an excerpt from his book The Turbulent Crown: The Story of the Tudor Queens about Anne’s execution.

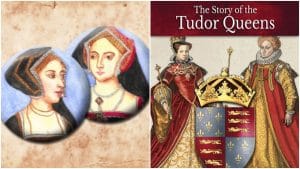

Roland’s publisher, MadeGlobal Publishing, is doing a special giveaway of two hand-painted portrait miniatures, painted by Roland – details at the bottom of this post. Over to Roland…

By tradition, executions normally took place in the morning with the Constable giving notice to his victims some hours before. But by daybreak no summons came. Eventually, the Queen was told that her death was to be postponed until after midday. “I hear I shall not die afore noon”, she said anxiously, “I am very sorry therefore, for I thought to be dead by this time and past my pain”.

It was not that Anne feared death; it was the waiting that unnerved her. The only comfort Kingston could offer was that when the time did come, Anne would feel nothing. The French executioner was exceptionally skilled and the blow would be ‘subtle’. But the Constable’s words of reassurance were dampened by further delay. The Frenchman had still not yet arrived, and Anne was to be given another day’s reprieve. To fortify herself, Anne returned to her devotions.

It was a sleepless night, but not only for the Queen. Alexander Alesius, a Scottish reformer living in London, was awoken by a nightmare in the early hours of 19 May. He had a horrific vision of Anne Boleyn lying on the scaffold with her head off. Disturbed and unable to return to sleep, Alesius paid a visit to his friend Thomas Cranmer at dawn. At Lambeth Palace, he came upon the Archbishop, not abed either, but pacing nervously in his garden. The Scotsman inquired as to his restlessness. Cranmer answered, “Do not you know what is to happen today?” Alesius shook his head. “She who has been the Queen of England upon earth”, the Archbishop said tearfully, “will today become a queen in Heaven”. Having heard her last confession in the Tower, he paid tribute to her innocence.

Later that morning, the official witnesses to Anne’s death – including Cromwell, Suffolk, Richmond, and the Lord Mayor – positioned themselves on a newly made scaffold. The headsman from Calais was also there, brandishing his double-handed sword. The platform had been built low so that only those closest could view the final ceremonial and hear the victim’s last words. Nonetheless, Anne’s execution was to be no private affair, but done with ‘open gates’, accessible to the common people. The ‘reasonable number’ Kingston expected had swelled to over a thousand Londoners, all drawn to an incredible and unprecedented event – the execution of the Queen of England. There was worry about the mood of the crowd. People had ‘spoken strangely’ of Anne’s condemnation. It was imperative that as soon as she was dead, any favourable account of her last moments must be suppressed. The rest of Europe must know her as ‘a cursed and venomous wh*re’ – as in the King’s own words – who was justly punished for her crimes. To make sure the official spin made its way overseas via England’s own ambassadors, all foreigners were ejected from the Tower.

The crowd waiting impatiently for the gory spectacle was not disappointed. At about 8 o’clock, the Queen came forward at last. For her final public appearance, Anne dressed carefully in a gown of grey damask edged with fur. A gabled hood, under which her long hair was tucked, framed her face. Determined to ‘die boldly’, Anne stepped onto the scaffold and addressed the crowd with a ‘smiling countenance’. The officials drew in their breath. Would the Queen ‘declare herself a good woman’ in her last moments and make mockery of the King’s justice?

To their relief, there were no surprises. Wanting to make a good end, and perhaps to protect her family from any royal reprisals, Anne made no accusation or criticism. But she admitted no guilt either. Following her brother’s example, Anne merely submitted herself to the law and prayed for the King, asking the crowd to do likewise for her. Anne’s only defence of her reputation was a reiteration of William Brereton’s enigmatic plea. “If any person will meddle of my cause”, she told the onlookers, “I require them to judge the best”.

With nothing more to say, Anne removed her headdress, knelt upon the straw, and received the blindfold. The executioner advanced and raised his sword. With a single deft swing, it was done. Death was quick and painless as had been promised her.

You can find out more about Roland’s book at http://getbook.at/turbulentcrown.

MadeGlobal Publishing is doing an amazing giveaway – two hand-painted portrait miniatures of Anne Boleyn and Mary Boleyn. These delightful miniatures, done in watercolour on cardstock and measuring 55mm each, were done by MadeGlobal’s own Roland Hui. Besides, being an author, Roland has a love for ‘limning’ or miniature painting. You can enter the giveaway at https://www.madeglobal.com/giveaways/hand-painted-miniatures/

but be quick, it ends at 1am BST on 21st May 2017.