Thank you so much to Lauren Mackay for sharing her thoughts on Eustace Chapuys, the Imperial ambassador, with us today as part of her book tour. I’ve been corresponding with Lauren for a number of years and I’m thrilled that she’s written a biography on Chapuys, a fascinating man and an invaluable primary source. Over to Lauren…

What made you want to write about Chapuys?

Eustace Chapuys has been on my mind for over a decade. He intrigued me from the very beginning: one of our most important sources, a vital narration of the Tudor period, and yet he was nothing more than a name at the bottom of a page. During my Master’s thesis on the Boleyn men, I found that Chapuys loomed large in my writing, and I felt it was time to tell the story of the Tudor court through his eyes.

Where did your research take you?

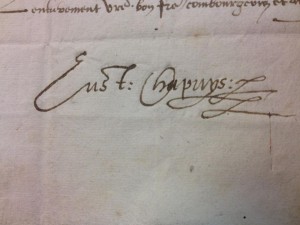

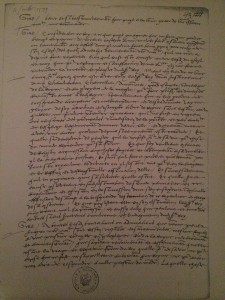

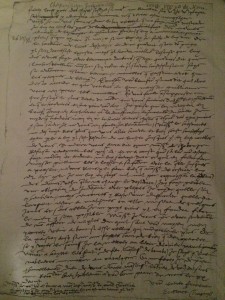

I travelled to Annecy, where he was born. Now part of France, Annecy was once a bustling market town, part of the independent state of Savoy. His portraits are hidden away in various galleries and schools in Annecy. I spent some time alone with them – I was transfixed. I also held his personal letters and despatches in Annecy and Vienna, travelled to Brussels to see the 18th century translations of some of the lost letters, as well as London, Lyon and Paris.

What were some of the most exciting letters you held?

The letters of January, April and May, 1536, as well as his last despatch from England. I remember rifling through 1535/1536, and coming to his letter following Katherine of Aragon’s death. His writing is erratic, he is agitated, distraught. There is an angularity to his form. Something shifted in him with Katherine’s death, and it is there on the page. Holding his letter of 17 May was a highlight. It’s partially in cipher, and Chapuys has scrawled in the margins, but it’s an incredible letter, allowing us a glimpse of his own thoughts of the coup against Anne, the condemned men, and Anne’s fears.

Why is Chapuys used so selectively as a source? A number of writers have described him as untrustworthy. Does this frustrate you as his biographer?

Any misuse of a source is frustrating, but it is the conscious effort to twist his words and belittle his principles which is most damaging. Attitudes towards Anne Boleyn have affected our perceptions, a simplistic analysis has been adopted: Anne is a victim, therefore Chapuys is the misogynistic, deceptive and insidious villain. Chapuys is one of Anne’s most important biographers, through his despatches she emerges as so much more than a mere victim, or ambitious harpy. His words allow for that nuance which is so often missing from her biographies. My research has demonstrated that Chapuys did not only refer to Anne as the Concubine. Even when he referred to her as the Lady, it is said that he “disgustedly” referred to her as such. But Chapuys referred to other women the same way, it does him a disservice to force such a hostile tone into his words. From 1529 to 1533, Anne was referred to as Anne Boleyn, The Lady, Mademoiselle Anne, Lady Anne etc. From 1533 to 1536, he refers to her as the Concubine once. The title crops up when he is under emotional stress. From 1536, after Katherine’s death and Henry’s reaction to it, something in him shifts, and he does become more hostile. It is also worth noting that Chapuys is careful to preface any rumours with his own opinion as to their credibility. Chapuys’ job was to provide Charles with accurate information, and he felt obliged to include every piece of information. If Chapuys did distort the truth or conjure up a story, Charles would have quickly found out from his other ambassadors and sources, and Chapuys’ reputation would be worth nothing. His observations could be harsh, but that does not make them untrue. He was often ahead of the game when it came to news, and there are numerous incidents in which he has discovered information before other embassies.

Did Chapuys believe the charges against Anne?

Not at all, and he was clear about that. Nor did he believe George had committed incest or was guilty of any crime. He admired George’s behaviour during his trial, and seemed shocked that he was convicted. Chapuys even notes that Henry’s decision to have George and the condemned men executed so close to Anne’s lodgings was a final, cruel gesture. Chapuys admired Anne and George in those last days, and their deaths continued to haunt him for weeks to come.

Did Anne Boleyn really “trick” Chapuys into acknowledging her?

So many historians have become fixated on this incident. There is no indication that Anne had engineered it at all. The original letter is very clear: Chapuys is aware that everyone is waiting to see how Anne and Chapuys will act when in the same room. He bows to the royal couple, which he has obviously done before, but this time Anne turns to acknowledge the bow. Chapuys seems surprised, and almost pleased by her behaviour, as though he’s worried she was about to insult him. He tells Charles that he finds her affable and courteous, and clearly states that he was making reverence to her. “She turned around to return the reverence I had made to her” There was no trick. Chapuys thinks no more of it, and goes off to dine with George Boleyn and the other councillors. Anne later asks why Henry did not allow Chapuys to dine with them. Considering France had cooled towards them, it is interesting that Anne seems to be considering the Imperial option.

Your PhD is on the Boleyn men, what is it like writing from perspectives of men who were on opposite sides of the board?

They barge in on each-other constantly in my writing, though Chapuys had a good relationship with George and Thomas. He found them both to be intelligent men, and admired Thomas’ skill in diplomacy. He found George a little aggressive when it came to religion, but he certainly never avoided them, and engaged in numerous conversations with them both. I think his reaction to George’s execution denotes his respect for them.

What else are you working on?

Apart from my PhD, I am also working on several journal articles, and my next book, which will be about Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk.

Giveaway

Lauren’s book, Inside the Tudor Court, was released in February 2014 and you can read my review of it on our Tudor Book Review site – click here. Amberley Publishing have kindly donated one copy of Inside the Tudor Court for a giveaway. All you have to do is comment below sharing why you want to know more about Chapuys by midnight on Friday 4th April (GMT) and one lucky winner will be picked at random. There will be further chances to win a book at the other stops on Lauren’s book tour:

- 1st April, Anne Boleyn: From Queen to History, author summary of the book

- 2nd April, Nerdalicious, author article about her research/travelling for the book

- 3rd April, On the Tudor Trail- Retracing the steps of Anne Boleyn, extract from Inside the Tudor Court

- 4th April, Tudor Book Blog, author interview

- 5th April, Tudorhistory.org, extract from Inside the Tudor Court

- 6th April, Le Temps Viendra: A Novel of Anne Boleyn, extract from Inside the Tudor Court, plus a brief guide to following in Chapuys’ footsteps in his home town of Annecy.

I want yo more about him because he seems to have been more than a mere ambassador, especially to Katherine in her extremity. That poor lady.

Hello, it’s very simple and a short explanation why I’d love the book, I am starting my journey into learning about Anne & the Tudor Court. I have read Chapuys name so many time but even following this article, have no real idea who he is and why he is relavent to the Tudor Court. Will Google hi right now, I’m intrigued!

You say that Chapuys only referred to Anne as “the Concubine” once between 1533 and 1536, but In one letter alone, in January 1536, in the English transcription Chapuys referred to Anne as “the Concubine” five times. Chapuys also used it in 1535 and when writing about the trial of the men in May 1536 he referred to Anne as “the said putain and Concubine”.

Is it all down to the English translators and transcribers of Chapuys’ letters mistranslating the words he uses? What is the original word he uses? Can you explain this a bit more? I know that Dr Ortiz and Charles V also used “the Concubine” in referring to Anne.

Thanks and thank you so much for taking the time to write this wonderful article, I do love Chapuys’ dispatches and I don’t agree with those who dismiss him as a source. A world without his despatches would be a difficult one for us Tudor researchers!

Hi Claire,

I was referring to occasions (letters), I wasn’t counting the individual references within each letter. He does use concubine and maîtresse. The Imperial embassies used the terms from 1529 onwards, but it took Chapuys years to feel so distraught that he needed to.

And yes, on occasion I have found words in the translations that are not in the original. Whether this is personal bias of the translators, or a just a mistake, we can’t be sure!

Thank you so much for clarifying that and that is the trouble when we are relying on translations. I can see why they would see Anne as a concubine, but “putain” is a much stronger word.

How fortunate to have the ability to read Chapuys original dispatches which undoubtedly will provide readers of your book with fresh insight into the characters and the unfolding drama of the era.

I want to know more about Chapuys because most people just think of him as the man who hated Anne and called her the concubine. He was more than that and even though I know he was close to Mary and Katherine I want to know how close and why he thought he should be there for Mary and look out for her after Katherine’s death. I also want to know what he thought of the other wives Henry VIII had 🙂

I’m intrigued by who he was and how he developed from his original posts in Savoy to being Katherine of Aragon’s right-hand-man. I want to know more about Eustace the man, the person, the human being.

What a fantastic article!! I would love the opportunity to know more about chapuys because I think he has the right to have his story told, and judged for his own words and his own merits rather than as the antagonist in the defence of another historical personage. Too many people are unfairly slandered in modern times in defence of another and I think it is about time chapuys is treated and respected as an important commentator of his time.

I would like to learn more about Chapuys because his dispatches offer an insight to Anne and her trial and the trials of the men. He offers descriptions of Court life from a different point of view. I may not agree with all of his opinions, but he was there, and I believe I could learn so much from him. How he felt about Katherine and Anne, and Henry.

I am generally interested in 16th century diplomacy and I have often heard about Eustace Chapuis, naturally. I’d very much enjoy to read his version of the events at Henry VIII’s court!

I would like to know more about Eustace Chapuys, because he is such an interesting figure in the Tudor Court. He stood by Catherine and Mary and without him or knowledge about what was happening back then would be really limited!

Why would I like a copy of this book? It’s simple actually. I’m a greedy Tudor history fan who gobbles up every piece of literature I can find. So please, choose me, so I can gobble up this book too!

Thank you, I enjoyed that. Eustace Chapuys was one of my favorite characters in “The Tudors”

I would love to read more about Eustace Chapuys and his connection with Katherine. Chapuys may have been one of the only persons to understand the heart of the Queen, and her dedication to the Lord her God, and to Henry.

After reading his dispatches at length for my dissertation on the fall of Anne Boleyn, I think learning more about him as a person would be helpful in understanding the way he viewed and interpretation the politics of The Tudor court

Because of him we know more about Catherine and Henry’s divorce but I personally don’t know a lot about him so would love to learn more about the man who provides us with so much information

I have read a lot about King Henry and his queens but not about the people around them. I figure you can never read too much history and he sounds like an interesting subject.

I’d like to know more about Chapuys’s life … not only because of his dispatches concerning Anne, but also because he stayed in Henry’s court, recording events afterwards. He was a key eyewitness to so much …. and, as a lawyer, I know how valuable it is to know about the background of such a key witness!

I have always wanted to know more about Chapyus, because he seems to be on the edges of everything I’ve read about Henry VIII & his wives. I think he was an intelligent & compassionate man, and he always tried to create a friendly relationship with them (Anne Boleyn, being the exception, I would never call their relationship friendly), and continued to try to keep Mary I in Henry’s mind. While I tend to be Team Elizabeth over Team Mary, she was named 2nd to the throne, Elizabeth being 3rd, & so deserved her chance to rule. He remained ever faithful to Catherine of Aragon until her death, & remained the only link between the Queen & her daughter. There is so much about him that I would really like to know…

I would really love this book. I know about the imperial ambassador, however that information is very little. I want to know more about the man and who he was besides an ambassador. I would love to expand my knowledge with this book on Chapuys.

I would love to know more about chapyus as in most of the books I have read about the divorce, Henry viii, Anne Boleyn, Catherine of Aragon, etc chapyus features quite a bit… I want to know more about him, seeing him feature in many books, seeing him referenced many many times makes me want to try and understand the man more. Also he is the ambassador that most tudor enthusiasts can name without thinking twice, but can’t say much more about him other than he was Spanish and didn’t like Anne Boleyn, I want to expand my knowledge of this character who features prominantly in Henry Viii’s reign

I would love to know more about chapyus as in most of the books I have read about the divorce, Henry viii, Anne Boleyn, Catherine of Aragon, etc chapyus features quite a bit… I want to know more about him, seeing him feature in many books, seeing him referenced many many times makes me want to try and understand the man more. Also he is the ambassador that most tudor enthusiasts can name without thinking twice, but can’t say much more about him other than he was Spanish and didn’t like Anne Boleyn, I want to expand my knowledge of this character who features prominantly in Henry Viii’s reign who really should have had a book before now

Great article!

I’ve always been fascinated by Chapuys. He seems like such an important character in the Tudor court and I’d like to learn more about some of the other things he did beyond what is widely publicised. I’d also like to learn more about his relationship with Princess Mary and how he councilled and supported her through the years.

Looking forward to this book!

Thanks

Ravin

I would like to know whether you came across any further reference as to who was actually doing the ‘much talk of a divorce’ as mentioned by Chapuys in a letter to the Queen of Hungary on 10th November 1541, as the news of Katherine Howard’s fall from grace began to leak out:

‘Wrote last Lent that this King, feigning indisposition, was 10 or 12 days without seeing his Queen, or allowing her to come in his room, during which time there was much talk of a divorce; but owing to some surmise that she was with child, or else because the means for a divorce were not arranged, the affair slept till the 5th inst.’ (Spanish Calendar, VI. i, No. 204.)

Thanks,

Marilyn

(Congratulations on the book, and the article in the BBC History Magazine.)

My love affair with Medieval and Renaissance era started in the 9th grade. I have my English and Social Studies teachers to thank for that. I was captivated by the rich history, shocked by the brutality , and interested in learning all that I could about this most complicated time.

As I grew older I began to focus on certain people. The Tudors and their era was of most interest. Back when I was younger, information was not at my fingertips as it is now. In order to find out information I relied on the library, which was limited in its history section. I began compiling a library of my own and now I not only have traditional book, but an e library as well. I am always looking to add to my collection and this book would be a wonderful addition.

Eustace Chapuys is someone whom I know very little about. This book appears to be an in depth biography about this man. It would be an adventurous read for me, discovering facts about someone whom I know virtually nothing of.

I’d like to have the book as I live in Oman and it’s difficult to get books here

Although I have mostly read and researched primarily Anne Boleyn, I have also really enjoyed learning about the Tudor court through other perspectives. I have recently read books on George Boleyn’s wife, Jane, as well as Thomas Cromwell. I would really love to experience this fascinating era in history through the eyes of Eustace Chapuys. I always admired his constant and unwavering loyalty to Catherine of Aragon and Mary Tudor and would be thrilled at the chance to learn more about him!

I think learning/reading more about Eustace Chauppy would be quite interesting. We hear so much about about him and his letters, yet know so little of the man’s life and chracter.

I would like to learn (and read more) about Eustace Chapuys due to the fascinating era of time he wrote about. I find what little I HAVE read about Eustace Chapuys so interesting and alway wish there was more information out there. I would love to read more!!!

Chapuys has always been a fascinating individual that held a unique position in that he could report what was going on at the Tudor court and not have to worry about getting the King’s favor like Henry’s English subjects. They had to do whatever it took to remain on good terms with Henry VIII or find themselves on the bad side of Henry’s temper and unpredictable mood swings (a place that no one wanted to be).

I believe that Chapuys was naturally on Katherine and Mary’s side in this situation in the beginning because he felt that both had been wronged and that the future of the Catholic Church in England was in peril. However, when events proved that Henry was determined to do as he pleased, throw off papal authority, dissolve the monasteries and marry whomever he chose to marry, it became apparent that no one was going to convince Henry to do anything he did not want to do once he had made up his mind and bent his conscience to that course of action.

I also believe that as he saw Anne’s position become increasingly insecure and the problem of having a living male child, the same as Katherine had, he may have started to pity her.

In addition, I think he was probably shocked, appalled and sickened when Anne was accused with the others of adultery and crimes against the King and was under threat of trial and execution. He probably figured, that the worse case scenario would be to have Elizabeth taken from the line of succession and a divorce/annulment from Anne.

For someone to go from a state of total devotion, moving heaven and earth for six years to make that individual your wife and Queen, only to execute her three years later, makes one wonder if Chapuys thought Henry had taken leave of his senses to resort to such measures.

If I could ask Chapuys one question that he would be able to answer honestly and frankly, without any fear of repercussions, would be his honest and true opinion of King Henry VIII after he had been through his six marriages. I would be most interested in his reply.

As a life long history fanatic I have read much about Chapuys however it has always been in connection to Henry, Anne, Mary and Catherine. I would like to know more about Chapuys the man and not the ambassador. He went above and beyond the role of ambassador to both Catherine and Mary and was a true friend and that in an age where money or fear could make one change alliances Chapuys remained loyal. Given this man’s integrity he would have laid down his life for the two women he admired and loved in its purest form.

I’m interested in nearly all things “Tudor” and am often asked who from that time period would I dine with if possible. Friends are amazed that I always say Eustace Chapuys, because he saw both sides of the coin and faithfully recorded it. I fear we would have less knowledge about the times without his both scholarly and gossipy writings..

I’m anxious to read this book! Thank you for writing it.

I’d like to read more about Chapuys because he always seems to be on the sidelines commenting on events in the Tudor court, and not as an individual in his own right. I had no idea, for example, that he respected Thomas and George Boleyn.

This is very exciting! I’ve actually been to Annecy and found it to be a charming little town – we ate breakfast in the shadow of that building whose photo is in your interview article…we were told that it had been a prison at some point in its history. I did not know when I was there that it was the Chapuys birthplace, although I’ve had a fascination with the Tudor era for decades and any mention of Chapuys has always made whatever I was reading that much more interesting.

I will absolutely have to read your book. For some time I have been very interested in contemporary accounts from the eras on which I’ve focused my reading for so long. As one of the main chroniclers of the events at the Tudor court, and of that exciting time of transition in Europe, your book is a must read and has now shot to the top of my list!

I admire him because, based on my reading, he seemed to have Katherine and Mary’s best interests at heart, more so than they did, most likely. I think he’d be a fascinating segue into other insights of Henry’s Court.

Ever since I began educating myself on Tudor history, Chapuys name appears in every thing I read. How interesting that he was right there on the sidelines of this tumultuous period. I would love to keep reading and earning about him.

I have become so much more interested in Chapuys; I have learned so much more about the man. He was a man of great mind, putting everything in perspective and not judgmental; handling situations must have been very stressful, and I admire that.

Elizabeth

At last – a book about Eustace Chapuys. He is always portrayed as such a sinister character. It will be interesting to learn more about him.

I would love to win a copy of author Lauren Mackay’s book on Eustace Chapuys. I always thought Eustace Chapuys to be fascinating person and I admired of how he’d stood up for Queen Catherine and Princess Mary.

I would like to learn more about the man behind the name… There is always reasons for things done and I would love to try and figure out if there was a motive behind any of his actions.

I want this book because I hope it will let me see a contemporary’s view point rather than a historian’s after the fact when perceptions have changed.

I want to know more about Chapuys because he had a front row seat to everything happening in the Tudor court. He might have been biased towards Katherine of Aragon, but I want to know how he viewed everyone else as well. It’s important to me to view both sides and draw my own logical conclusion.

Chapuys chronicled so many events during his years in the Tudor court and in such a detailed manner that I know this book about him would greatly increase the reader’s knowledge about those times, and that is what interests me (as well as reading his personal observations about Anne Boleyn).

My first experience with thel Tudors came in 1972 when my father gave me a book for my birthday. It was called “A Crown for Elizabeth”, written by Mary M. Luke. I was 12 and hooked! Dad was a history teacher and he was more than happy to supply me with as many books as I wanted on the subject. 44 years later, I’m still hooked! I would love to have a copy of Lauren’s book. Chapuys has long intrigued me…he was a shadowy figure in a lot of books a blurb here and there about his devotion to Katherine and his animosity towards Anne, but very little about the man himself.

I have been intrigued by him since I read his fair he was about Anne’s trial, not

Letting his personal feelings cloud his judgement. He never married so I

Wonder if he had ever taken orders? He was an expert in canon law, apparently,

I look forward to this book and the one on George boleyn!

I’ve always been intrigued with the Tudors, and especially with Henry VIII and his court, but it’s only been the last couple of years that I’ve become curious about Chapuys. I’m really looking forward to reading this new book!

Chapuys played a vital role at court. With his many reports, we can gain a better understanding of the real court vs what we have seen on tv or assumed in what we read. Another part of the puzzle, another great way to spend the afternoon

I want to know more about Chapuys because he seems like a compassionate fellow in all the movies, but cunning and sometimes manipulative in books. I’d like to see him from another angle.

I have been fascinated with the Tudors since I was 5 and my Dad bought back a library book about all the kings and queens of England. I have never even hear of Chapuys – why, I don’t know – but I have a great desire to find out all about him!

I am just starting to learn about the Tudors and I would love a copy of this book to help me understand more about them especially Anne Boleyn.

I am thrilled to find a biography of Chapuys! My cousin and I have been interested in the Tudor Period for many years and a definitive biography is a God send for us. I am currently reading a new biography of Anne, by Susan Bordo “The Creation of Anne Boleyn”. I haven’t studied her bibliography yet to see who she is citing, but I would think your book would be too new to have been a source, such a pity. Chapuys plays such a major role in our knowledge of Anne.

I cannot wait to finish this to read yours!

Best of luck with your tour, we in the colonies will be reading it!

Judy Cobb

Auburn, AL

I’m enjoying all these posts. You can also purchase the book here:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/aw/d/1445609576?pc_redir=1395855101&robot_redir=1

http://www.bookdepository.co.uk/Inside-Tudor-Court-Lauren-Mackay/9781445609577

I have always wanted to know more about Chapuys the man. He is this great source of information but it always seemed like there was so little information about him. I’d like a better picture of him to set against my knowledge of the rest of the players at the Tudor court.

I would love this book! Why? because I’m soooo addicted to anything Tudor. I’ve seen Chapuys name many times while researching and reading and would love to know more about him.

Very grateful for both this research as well as the book. Thank you for sharing your enthusiasm and expertise with the rest of us!

Looking forward to this book and a first-hand account of the Tudor court. I have read many books on Henry VIII , his wives and court several years ago but recently retired and have more time to spend on my hobby. This book is going right to the top of my wish list. I am looking forward to reading it. I am particularly interested in Anne and how fast her downfall was as well as the other queens, What were the thoughts of undying love and then the executioner’s block three years later, what were the thoughts of the court at that time? Anxious and excited to get a copy.

I can’t wait to get this book–Chapuys has been SO instrumental in helping form opinions about people in the Tudor court, I am very anxious to learn more about him. Great interview!

Chapuys had always been simply a name below information about the Tudor period. That is, until I watched “The Tudors”, he became a more “real” person to me and I was so moved by the portrayal of him. I would love to dive in a little deeper to learn about who he was, as I believe he’s probably very intelligent & so adept at surviving Henry’s Court and managed to serve very long while still maintaining his head! He had to really be good, to come out of that in one piece, while maintaining his religion & his loyalties to Katherine & Mary. Simply brilliant! Thanks for the info! 😉

No one can read about the Tudors and not come across Chapuys, but knowing of him rather that about him are two different things, this is why I will find this book intriguing and a must read..a new insight into a main ‘player’ at Henry’s court.

I’d like to win the book as i find the man endlessly fascinating. I’m a huge Tudor history fan and i’ve read so much about this man over the years it would be great to learn more about him.

I have wanted to read a biography about Chapyrus for many years and have been very surprised that there was never one before now. There are of course his reports and letters and there is an early work very rare work that brings the diplomatic correspondance together but is not accessible to the public and we could not own this. In this work by Lauren Markey the Ambassador and Chapyrus the man are brought to life and Anne, Mary, Henry, Katherine etc through his wrting and emotions. The emotional side of Eustace is clear, especially his fears and concerns that Mary’s life may be in danger and it is here that he speaks more angrily of Anne. He is under great stress and pressure at times like this and this may colour his views a little. I was keen to read a book that takes Chapyrus seriously as a source and does not dismiss him. He in many cases is the best or even only intimate source for Anne and behind the scenes at the Tudor court.

I am very excited at this book and hope Lauren good luck and very good success in her doctors degree and her future success. She is a very talented young woman and has a natural talent for history, for writing and for bringing to life real human beings who seem veiled, even when we have their writing, by getting to the man and the soul behind those letters and diplomatic statements.

I know virtually nothing about Chapuys, except that he is always shown in a bad light. From your interview there is obviously more to this interesting man than Anne’s enemy. I would like to read more about his observations on Anne and Henry’s other wives and the royal court. The author has done phenomenal research.

I always found it interesting that Chapuys obviously had more interest in Katherine due to her relationship to Charles, yet had respect to some degree for Anne. He did love Katherine in all the courtly ways expected of him, but believed Anne was NOT guilty of all she was accused of. He seemed to be a good example of what was expected in court life. Do your duty happily, and rarely show your true feelings. If you want to be there a while anyway.

And the winner is……

Charlie Fenton!

Congratulations, Charlie, I have emailed you for your address.