Over to Gareth…

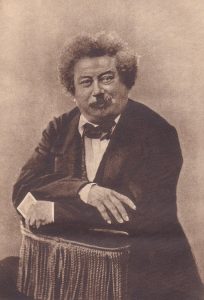

“You have heard of King Henry’s amours, always dissolute – sometimes fatal?” – Alexandre Dumas, Catherine Howard (1834)

After she was executed on February 13th, 1542, Catherine Howard, Queen of England and Queen of Ireland,1 passed not just from this life, but also into memory and its kinsman, fiction. Tolstoy’s remark that a king’s life becomes history’s slave is particularly apt in the case of Catherine Howard, who has given the world two spectres – one of sin, the other of sorrow. While she remained in living memory, interest in Catherine survived to produce spasms of remembrance for the rest of the sixteenth century. Almost immediately, there was an attempt to rewrite Catherine’s story as a grand love affair, a task undertaken by a Spanish merchant living in Tudor London. His tale, which included and possibly invented one of the most famous misquotes associated with Catherine Howard, proved enduringly influential.

The account, generally nicknamed “The Spanish Chronicle”, does not get off to a promising start with its Howard narrative when it misidentifies Catherine as Henry VIII’s fourth wife, rather than his fifth. The chronicler, whose identity is still a subject of debate, writes, “The King had no wife who made him spend so much money in dresses and jewels as she did, who every day had some fresh caprice. She was the handsomest of his wives, and also the most giddy. The devil, who is never idle, put it into this Queen’s heart to fall in love with a gentleman who, before the King’s marriage with her, was very much in love with her, and who was well beloved by him”. When this adulterous affair is discovered, the chronicle recounts how Queen Catherine was questioned by Thomas Cromwell, still alive in the merchant’s faulty but energetic memory. (Cromwell was executed over a year before Catherine’s downfall.) Queen Catherine and her lover are subsequently executed on the same day as one another (in fact, Culpepper perished on December 10th, 1541, two months before Catherine). On the scaffold, the chronicler’s Catherine addresses the crowd with the following words, “Brothers, [I swear] by the journey upon which I am bound I have not wronged the King, but it is true that long before the King took me I loved Culpepper, and I wish to God I had done as he wished me, for at the time the King wanted to take me he urged me to say that I was pledged to him. If I had done as he advised me I should not die this death, nor would he. I would rather have him for a husband than be mistress of the whole world, but sin blinded me and greed of grandeur, and since mine is the fault mine also is the suffering, and my great sorrow is that Culpepper should have to die through me.” The executioner kneels to ask her pardon, and Catherine then utters the unforgettable romantic vow, “I die a Queen, but I would rather die the wife of Culpepper. God have mercy on my soul. Good people I beg you pray for me.”2

The Spanish Chronicle’s story, and particularly Catherine’s third-to-last sentence, is without a scintilla of evidence. It is Catherine’s “let them eat cake” equivalent – a memorable piece of oft-repeated nonsense. The eyewitness accounts of the real execution are very clear that Catherine made a conventional speech – had she said anything like the words given to her in the Chronicle’s story, it would have been one of the most remarkable exits in Tudor history and one condemned, and remarked upon, by her contemporaries.3

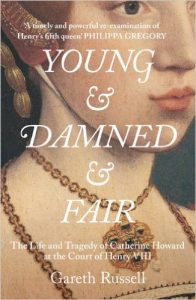

A more thoughtful and honest contemporary reflection on Catherine Howard’s downfall comes from George Cavendish, a talented writer who had once served as a gentleman-usher to Cardinal Wolsey. In retirement, Cavendish wrote a series of first-person monologues which he put into the mouths of the Henrician court’s most famous casualties. Cavendish’s depiction of Catherine and Culpepper is remarkable for the restrained but tangible sympathy he displayed for the dead queen. I discuss Cavendish’s depiction of Catherine, and other sixteenth-century attitudes towards her, in the final chapter of my book “Young and Damned and Fair”.4 Rather than repeat myself too much here, I will move on to later depictions, after everyone who had known the historical Catherine was long dead.

For the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries’ debates over the importance of Protestantism and the power of monarchy, Catherine Howard’s story offered little to excite historians, polemicists, or playwrights, unlike that of her cousin and predecessor, Anne Boleyn, who began her long ghostly career as a favourite of scholars, novelists, and dramatists. With her typical panache for a grand debut, Anne’s first foray into fiction was courtesy of William Shakespeare – since then, for better or worse, Boleyn has never been out of the spotlight for very long. In contrast, it was not until the nineteenth century that Catherine once again became an object of sustained interest.

Dumas’s play begins with a romance between an eighteen-year-old Catherine, scion of an ancient noble house yet raised in genteel poverty, and a young man called Athelwold. Fearful that Catherine’s earlier hardships have made her greedy, Athelwold has hidden from her the fact that he is the Earl of Northumberland and that, when they are apart, he resides at court where Henry VIII is divorcing Anne of Cleves and looking for a new wife. In the King’s words, “this time my queen shall be chosen from amidst the people – she must be young that I may love her, beautiful that she may gratify my pride, and wise that I may fearlessly confide in her discretion.”5 Catherine Howard’s ancestry and beauty make her a perfect candidate. One courtier assures the King that Catherine even excels “the beauty of Anne Boleyn, the grace of Jane Seymour” and that she will thus make a wonderful queen consort. A horrified Athelwold tries to save Catherine from Henry’s advances by offering her a potion that will produce a temporary coma with the appearance of death, not too dissimilar to the one taken by Shakespeare’s Juliet. However, when she hears that the King desires her, Catherine’s ambitions persuade her to leave Athelwold, present herself as a single woman, and accept Henry’s proposal. Driven mad by despair, Athelwold fakes his own death and then proceeds to “haunt” Queen Catherine. One evening, Catherine and an unhinged Athelwold are caught in her bedroom by the King, who assumes the worst. Athelwold chivalrously forgives Catherine for her earlier mistreatment of him and chooses to accompany her in death, since “We have reposed in the same bed – we will mount the same scaffold – [we] will lie within the same tomb.”6

Like many of Dumas’s works, “Catherine Howard” owed much to earlier authors. In this case, the premise is highly similar to a successful play called “Virtue Betray’d”, first published in English in 1682, and inspired by the life of Anne Boleyn, who had been actually been romantically involved with the future Earl of Northumberland as a young woman. Unlike “Virtue Betray’d”, Dumas’s “Catherine Howard” was neither a financial nor critical success. Although the play was translated into English two decades later, it did not enjoy many subsequent revivals.

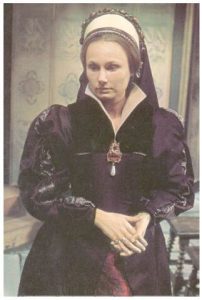

However, just over one hundred years later when the British motion picture “The Private Life of Henry VIII” premiered at the Radio City Music Hall in New York, Catherine’s story had become a financial goldmine.7 “The Private Life of Henry VIII”, which focuses most of its narrative on Catherine’s rise and fall, made nearly a 1000% profit on its initial run. Twenty years later, when it continued to be periodically re-released in British and American cinemas, it was still capable of bringing in about £10,000 a year.8 Like Dumas, the film’s director and co-writer Alexander Korda portrayed Catherine as a young, beautiful, charming but greedy woman, who pursued a path of deliberate self-aggrandisement until she is destroyed by falling in love. In many ways, they echoed the Catherine of “The Spanish Chronicle” when she spoke of her “greed of grandeur, and since mine is the fault mine also is the suffering, and my great sorrow is that Culpepper should have to die through me.” Catherine is both condemned and redeemed by love, having fallen into trouble through ambitions that are unnatural or unlikable in a woman.

In the century between Dumas’ and Korda’s versions of her, there had been an explosion of interest in Catherine Howard and the Tudor clan. As mentioned, Anne Boleyn had, like Mary, Queen of Scots and Elizabeth I, been an object of fascination for centuries, but it was only in the Victorian era that Catherine and other less significant members of the family became the focus of sustained academic and popular attention. Far more so than anything left by her contemporaries, the ways in which Victorian scholars approached Catherine Howard shaped how she was, and is, viewed. Victorian historians performed their craft with unrepentant solecism. The growth of Victoria’s empire, the increasing prosperity throughout her kingdom, and corresponding faith in the superiority of Britain’s political system had nurtured a widespread belief in the manifest destiny of Britannia. To this worldview, Britain’s history was one in which she had moved with inexorable, glorious momentum through Magna Carta, the Reformation, the Elizabethan age, and the Glorious Revolution to rid herself by a process of cultural evolution of despotism, superstition, and foreign interference. For his role in the Break with Rome, “the hinge on which all [our] modern history turned”, Henry VIII was often presented as one of the founding fathers of the British Empire by his Victorian and Edwardian admirers, who argued that his actions “averted greater evils than those they provoked”.10

The less I say about this scandalous matter, the purer my pages will be… Catherine Howard blackened the blue blood of the Howards, but fortunately she left no descendant to bear the stain; and whatever doubt there may be about Anne [Boleyn]’s guilt, there is none about Catherine’s.12

Yet, the nineteenth century was also an era of purple-prosed romanticism and its preoccupations with the perils of temptation against feminine frailty. Jane Austen excoriated Henry VIII, while praising the martyr-like virtues of Anne Boleyn; Charles Dickens thought Henry VIII had been “a disgrace to human nature, and a blot of blood and grease upon the History of England”, and the historian and Conservative MP Sir Charles Oman was repulsed by “Henry’s unbounded selfishness, of his ingratitude to those who had served him best, of his ruthless cruelty to all who stood in his way … [the] story of his reign develops each of these traits in its own particular blackness.”

Perhaps the most influential defence of Catherine came from the pen of Agnes Strickland, a strikingly beautiful and equally confident author whose works of history were so successful that they arguably birthed the genre of popular history.13 Agnes’s multi-volume “Lives of the Queens of England”, co-written with her more publicity-averse sister Elizabeth, presented Catherine as the victim of an abusive upbringing. Victorian publications were often heavily didactic and, while Strickland accepted that Catherine Howard as a “fallen woman” could not be presented as inspirational, she insisted that she could be pitied as well as held up as a warning: –

The career of Katharine Howard affords a grand moral lesson, a lesson better calculated to illustrate the fatal consequences of the first heedless steps into guilt, than all the warning essays that have ever been written on those subjects. No female writer can venture to become an apologist of this unhappy queen, yet charity must be permitted to whisper, ere the dark pages of her few and evil days is unrolled.14

The Victorians and Edwardians thus distilled two competing versions of Catherine as either vixen or victim, a dichotomy that was repeated with slight variations in most twentieth-century interpretations of her. Some continued in the vein of Strickland, portraying Catherine as a figure “surely more worthy of pity than condemnation”, a girl let down on all sides by those who knew her, manipulated as “a mere puppet in the hands of Norfolk and [Bishop Stephen] Gardiner”, who then abandoned her when she needed them most.15 In the early twenty-first century, Strickland’s version of a brutalised, betrayed pawn has been revitalised through claims by some of her biographers that Catherine Howard was a “vulnerable and abused child”.16 Elsewhere, the more critical school of thought espoused by Henry’s imperialist defenders has survived, albeit stripped of the florid patriotism that birthed it. A bestselling biography of Henry VIII, published in 1929, concluded that Catherine had been “a juvenile delinquent”, a phrase reused verbatim in Lacey Baldwin Smith’s acclaimed biography “A Tudor Tragedy: The Life and Times of Catherine Howard”.17 And, while Tudor enthusiasts often despair at the alleged inaccuracies of silver screen versions of Henry VIII’s family, the impact of non-fiction biographies reaches far beyond libraries and onto film sets. If they cannot always replicate every historical detail, it is still from the pens of academics that dramatists seek information when they research their scripts, thereby producing Catherines in popular culture that often closely reflect the interpretation of Catherine’s personality given by recent scholars.

As they grapple between the two, authors of modern fiction based on her life have reworked Catherine Howard’s friends, beaux, enemies and relatives many times. Her alleged lover Thomas Culpepper has been romantically involved with Catherine’s confidante Lady Rochford; Catherine has been innocent of adultery, guilty, or almost guilty; her confidante Lady Rochford has been mad, vicious, a saboteur or a bribe-taking sociopath. She has loved Catherine, hated Catherine, and remained coldly indifferent to her. Catherine has been a chaste and devout Catholic; she has been a seductress; she has harboured lesbian thoughts for Anne of Cleves. The Victorian dichotomy remains potently influential, yet it inevitably was also altered by interactions with feminism and changing attitudes towards gender.

Jessica Smith’s 1969 novel “Henry Betrayed” fixed on Catherine through the eyes of a fictitious childhood companion, Clarissa Daily, who befriends Catherine when she arrives at the Dowager Duchess’s mansion “without a trunk or any possessions whatsoever”.21 The Dowager, depicted as deliciously self-absorbed, barely notices that Catherine has arrived in penury and instead “drew the child in a kindly embrace, said she felt sure such a pretty little girl was as good as she looked, advised her to do as she was told, and put her in the charge of a Mistress Isabel, who was more preoccupied in her own forthcoming wedding than in the care of a poor relation”.22 “Henry Betrayed” is unusual in Catherine Howard-inspired novels, in depicting her as guilty of adultery with both Dereham and Culpepper. Lady Rochford accepts gifts from both men in return for arranging secret meetings with the Queen. The historical Dereham’s involvement with piracy when he was in Ireland was maximised and the novel writes of Catherine’s “delicious thrill in the masterful possessiveness of the bold buccaneer”.sup>23 Shortly before she is ruined, Catherine and Dereham are in bed together when they hear the King’s entourage approaching, so Dereham “escaped through the Queen’s window, this time stark naked, and Katharine hastily threw his clothes after him, taking great care that nothing was left behind, and then she opened the door to the waiting King”.24 The novel ends with Clarissa the narrator visiting Dereham, by then “just a heap of twisted humanity, groaning and crying out most pitifully”, shortly before his execution. The novel’s epilogue has the narrator kneeling in grief “beside the grave of the once-happy, thoughtless, kind-hearted girl who had been Queen of England”.25

“Henry Betrayed” is also noteworthy in its depiction of Catherine as both sympathetic and willingly sexually-active, a break from previous depictions that generally assumed she could not be the former if she had been the latter. Admittedly, in the same year as “Henry Betrayed” was published, a non-fiction study of the Tudor dynasty, written by a female historian, judged Catherine to have been “a poor, silly little trollop”, but as the impact of feminism and new views on sexuality grew such views became less prevalent.26 In 1995, the American writer Karen Lindsey praised Catherine as “a woman who enjoyed both sex itself and the admiration she got … from the perspective of a presumably more enlightened age, we should be able to recognize a kind of courage in her reckless affair with Culpep[p]er. Kathryn Howard was a woman who listened to her body’s yearnings, and in spite of all she had been taught, understood that she had a right to answer those longings. She was willing to risk whatever it took to be true to herself.”27 David Starkey, in his 2003 study of Henry VIII’s marriages, summarised the impact of the last half of the twentieth century on Catherine’s reputation when he wrote, “As a child of the sixties, I can describe Catherine’s promiscuity without disapproval … The long, withdrawing roar of Victorian morality inhibited generations of historians from treating this with anything other than disapproval and distaste. But we are past that now. We can confront sex as a fact, not as a sin. We can even, if pushed, see a sort of virtue in promiscuity.”28

Gareth Russell is the author of Young and Damned and Fair, a new biography of Queen Catherine Howard, published in 2017. He is also the author of several history books and the Popular series of novels.

Gareth will be back with another article, “Haunted Galleries: Visiting the sites of Catherine Howard’s life”, and a giveaway tomorrow.

Book blurb:

In the five centuries since her death, Catherine Howard has been dismissed as ‘a wanton’, ‘inconsequential’ or a naïve victim of her ambitious family, but the story of her rise and fall offers not only a terrifying and compelling story of an attractive, vivacious young woman thrown onto the shores of history thanks to a king’s infatuation, but an intense portrait of Tudor monarchy in microcosm: how royal favour was won, granted, exercised, displayed, celebrated and, at last, betrayed and lost. The story of Catherine Howard is both a very dark fairy tale and a gripping political scandal.

In the five centuries since her death, Catherine Howard has been dismissed as ‘a wanton’, ‘inconsequential’ or a naïve victim of her ambitious family, but the story of her rise and fall offers not only a terrifying and compelling story of an attractive, vivacious young woman thrown onto the shores of history thanks to a king’s infatuation, but an intense portrait of Tudor monarchy in microcosm: how royal favour was won, granted, exercised, displayed, celebrated and, at last, betrayed and lost. The story of Catherine Howard is both a very dark fairy tale and a gripping political scandal.

Born into the nobility and married into the royal family, during her short life Catherine was almost never alone. Attended every waking hour by servants or companions, secrets were impossible to keep. With his research focus on Catherine’s household, Gareth Russell has written a narrative that unfurls as if in real-time to explain how the queen’s career ended with one of the great scandals of Henry VIII’s reign.

More than a traditional biography, this is a very human tale of some terrible decisions made by a young woman, and of complex individuals attempting to survive in a dangerous hothouse where the odds were stacked against nearly all of them. By illuminating Catherine’s entwined upstairs/downstairs worlds, and bringing the reader into her daily milieu, the author re-tells her story in an exciting and engaging way that has surprisingly modern resonances and offers a fresh perspective on Henry’s fifth wife.

Young and Damned and Fair is a riveting account of Catherine Howard’s tragic marriage to one of history’s most powerful rulers. It is a grand tale of the Henrician court in its twilight, a glittering but pernicious sunset during which the king’s unstable behaviour and his courtiers’ labyrinthine deceptions proved fatal to many, not just to Catherine Howard.

The book is available from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk and other bookshops.

Notes and Sources

- For the proclamation regarding Catherine’s Hibernian title, see LP, XVI, 974.

- Martin A. S. Hume (ed.), Chronicle of King Henry VIII of England, being a contemporary record of some of the principal events of the reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI, written in Spanish by an unknown hand (London: George Bell and Sons, 1889), pp. 77-86.

- For the author’s discussion of contemporary accounts of Catherine’s execution, see Gareth Russell, Young and Damned and Fair: The Life of Catherine Howard, Fifth Wife of King Henry VIII (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2017), pp. 320-321.

- Russell, Young and Damned and Fair, pp. 331-33.

- Alexandre Dumas; W. D. Sutter (trans.), Catherine Howard: A Romantic Drama in Three Acts (London: Samuel French, 1855), Act I, scene i.

- Dumas, Catherine Howard, Act III, scene i.

- The Private Life of Henry VIII (London Film Productions, 1933), written by Lajos Biró and Arthur Wimperis; directed by Alexander Korda, with Binnie Barnes (Catherine Howard), Charles Laughton (Henry VIII), Elsa Lanchester (Anne of Cleves) and Robert Donat (Thomas Culpepper).

- Paul Tabori, Alexander Korda (London: Oldbourne, 1959), pp. 129-30.

- Tabori, Alexander Korda, pp. 126-7.

- A. F. Pollard, Henry VIII (Aberdeen: Longmans, Green and Co., 1951), p. 352. This edition is a reprint; Pollard’s biography was first published in 1905.

- James Anthony Froude, History of England from the Fall of Wolsey to the Death of Elizabeth (London: John Parker and Son, 1858), IV, ii, pp. 129, 131.

- F. Stoney Sadleir, A Memoir of the Life and Times of the Right Honourable Sir Ralph Saldeir (London: Longmans, Green, & Co., 1877), p. 70.

- For a good discussion of the impact of the Stricklands’ work, see Antonia Fraser Agnes Strickland’s Lives of the Queens of England (London: Continuum, 2011)

- Agnes Strickland, Lives of the Queens of England from the Norman Conquest (Bath: Cedric Chivers, 1972), III, p. 98.

- Martin Hume, The Wives of Henry the Eighth and the Parts They Played in History (London: Eveleigh Nash, 1905), p. 396; Michael Glenne, Catherine Howard: The Story of Henry VIII’s Fifth Queen (London: John Long, 1948), p. 87.

- Joanna Denny, Katherine Howard: A Tudor Conspiracy (London: Portrait, 2005), p. 88.

- Francis Hackett, Henry the Eighth (London: Jonathan Cape, 1929), p. 456; Lacey Baldwin Smith, A Tudor Tragedy: The Life and Times of Catherine Howard (London: Reprint Society, 1962), p. 159.

- The Six Wives of Henry VIII: Episode 5, Catherine Howard (BBC, 1970), written by Beverly Cross and directed by Naomi Capon, with Angela Pleasence (Catherine Howard), Keith Michell (Henry VIII), Patrick Troughton (the Duke of Norfolk), Sheila Burrell (Lady Rochford), Simon Prebble (Francis Dereham) and Ralph Bates (Thomas Culpepper).

- Beverly Cross, Catherine Howard: A Play (London: Samuel French, 1973), Act III, p. 45.

- Henry VIII and his Six Wives (BBC, 1972), written by Ian Thorne and directed by Waris Hussein, with Lynne Frederick (Catherine Howard), Keith Michell (Henry VIII), Michael Gough (the Duke of Norfolk), Charlotte Rampling (Anne Boleyn) and Bernard Hepton (Archbishop Cranmer).

- Jessica Smith, Henry Betrayed (London: Robert Hale, 1969), p. 11.

- Ibid.

- For Dereham’s time in Ireland and alleged piracy, see Russell, Young and Damned and Fair, pp. 153-154, 268.

- Smith, Henry Betrayed, pp. 109-10.

- Ibid., pp. 130, 155.

- Alison Plowden, The House of Tudor (New York: Scarborough Books, 1976), p. 114.

- Karen Lindsey, Divorced Beheaded Survived: A feminist reinterpretation of the wives of Henry VIII Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 1995), p. 169.

- David Starkey, Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII (London: Vintage, 2004), pp. xxv, 654.

- Smith, A Tudor Tragedy, p. 189.

- Henry VIII (Granada Television, 2003), written by Peter Morgan and directed by Pete Travis, with Emily Blunt (Catherine Howard), Ray Winstone (Henry VIII), Mark Strong (the Duke of Norfolk) and Joseph Morgan (Thomas Culpepper).

- The Tudors, Series 4 (Peace Arch Entertainment, 2010), written by Michael Hirst, directed by various, with Tamzin Merchant (Catherine Howard), Jonathan Rhys Meyer (Henry VIII), Torrance Coombs (Thomas Culpepper), Allen Leech (Francis Dereham) and Joanne King (Lady Rochford).

- William Nicholson, Katherine Howard, first performed at the Chichester Festival Theatre on 9 September 1998, with Emilia Fox (Catherine Howard), Richard Griffiths (Henry VIII) and Julian Rhind-Tutt (Thomas Culpepper). In this script, Catherine does not commit adultery.

- For two well-received biographies that do argue for Catherine as the victim of abuse in her early years, see Conor Byrne, Katherine Howard: A New History (Lúcar: MadeGlobal, 2014) and Josephine Wilkinson, Katherine Howard: The Tragic Story of Henry VIII’s Fifth Wife (London: John Murray, 2016).

I view Catherine Howard as a young and vulnerable woman who marries an aging Henry the VIII ,very probably almost ? Impotent due to his obesity ,to the illneess in his leg ……his irritability …..his frustrations acumulated ….but still wanting to titillate his senses with a young and beautiful woman like Catherine . She was to my mind very probably introduced to the king to make sure her family progressed in the king’s favour .It is very unlikely that she fell in love with the King …..and very probable that she did fall in love with Culpepper..I think she was very rash and very brave and full of courage considering the awful cicumstances .A bloody end that she did not deserve .

The Tudors did a right job on Katherine Howard as a brainless, spiteful, pretty, carefree bimbo. However, they were not the first, but certainly the worst and they even threw in a brothal style home. Katherine is still seen by most people as uneducated, just because she wasn’t the intellect of Anne Boleyn. Again nonsense. She was the daughter of a younger son but the granddaughter and niece of a great family. She lived in a typical household but lost her parents early in life. However, again contrary to popular myth she was not neglected and did have adult supervision. She was taught how to run a great household and music and could read and write. She may not have been a bookworm, but few women of noble families were. Noble families collected books and Katherine as Queen had at least four dedicated to her, but books were still expensive, in spite of printing. The Dowager Duchess was wealthy and had a great household to run and several young women and gentlemen. Officially there were rules on modesty and discipline, but here supervision fell short. It is obvious that those supervisors in charge at night neglected their duty as the key to the dormitory was easy to steal and sneak in gentlemen. There were young men in the household and people employed by the Duchess to add to the young ladies education. No young woman of a decent family, especially a royal or noble or gentlewoman could expect to be any use as a wife without some form of education. We cannot project modern ideas of education onto sixteenth century women. Just because no formal education in a college was offered or they didn’t all get the unusual advanced education of Anne Boleyn and Katherine of Aragon or Margaret Roper, doesn’t mean they were unintelligent or uneducated. Anne Boleyn was not a typical woman of her day and even she had to conform to male control, something she resisted as Queen. Katherine had to learn statecraft, decorum, household maintenance and control, music, needlework, a basic knowledge of herbs, to run her kitchen, staff, everything required to keep a large house clean, read and write, basic accounts, everything she would need to run and control a complex household. You can’t do any of this as a brainless bimbo. Jane Seymour would have received a similar education but within the context of her own home and she certainly would not have been suitable to serve two Queens for a number of years shut up at Wolfe Hall not doing anything. She is another lady who is maligned as dim and uneducated without any evidence being offered by those commentators. Sadly for Katherine, her reputation has suffered more because she has been caught up in scandal.

Due to a lack of vigilance she was firstly at a young age pressured into inappropriate behaviour by her music teacher at the age of 12 to 14 which we would view as abuse. At first Katherine gave him what he wanted but then when it was discovered she had closer supervision as she wasn’t left alone. The Duchess did also dismiss him. Both Katherine and Mannox were disciplined but Mannox was a nuisance. Later she had a consensual relationship with a gentleman called Francis Dereham who was well known to the household. Several young ladies invited gentlemen to their dorm and they enjoyed parties and romps of an evening. Here the staff were negligent.

Katherine Howard became a lady at court when she was about sixteen to Anne of Cleves, which is further proof that she had received at least a basic education. She would have been finished here at court, so she knew how to behave at court. There is further proof that she knew how to behave because she is described as playing her part as a great lady by David Starkey and sources described her as having grace. In public at least there was no sign of the spoilt brat in the Tudors. In Lincoln and York she was praised for her charm and beauty and her carriage of herself.

Katherine has a mixed reputation as Queen. On the one hand there is Katherine the fun loving, dress loving, dancing party girl and yes, she loved pretty dresses and which teen is not going to enjoy being spoilt rotten by the King, who lavished her with fine things. Part of this was expected anyway as Queen of a glittering Court. On the other hand we have Katherine the flirt whose immoral behaviour led to her tragic death in the Tower, aged little more than 19 at most.

We don’t hear about Katherine the generous lady, or Katherine who helped people or even Katherine the spiteful. Katherine also had a difficult relationship with Mary, who saw her as not being worthy of her father. Mary was also fond of Anne of Cleves and she saw Katherine as a usurper. As far as Mary was concerned, Anne was still Henry’s lawful wife, a position Anne of Cleves took although she had submitted to the annulment of her marriage. Katherine Howard was also an insecure Queen, because of rumours that Henry was seeing Anne of Cleves and would renounce her. This shows a very sensitive and vulnerable young woman with genuine anxieties. She was not cut out for the private demands of a Queen, being separated from Henry for periods of time and her insecurities show here as well. She was often angry with her ladies and could be spiteful, sharp and controlling. She could also be generous, as evidenced by her making clothing for Margaret Pole and I know Gareth Russell dismissed this as being made on the orders of Henry as a duty to provide prisoners with clothes, but she sowed these herself. She gave gifts away and she helped some of her friends. She was also good at her role as intercession and generally was probably a very decent Queen.

Unfortunately, Katherine’s past caught up with her, but at the time we must remember that she was an unmarried girl of fifteen having fun, before it was decided she is now old enough to marry. She could have been married to a gentleman or noble anyway in 1539 or 1540 and her time at court could be seen as a coming out and a chance to be seen by eligible families. However, Katherine caught the King’s eye, he courted her and she agreed to be his wife and no, she wasn’t forced to marry him. He offered her power and prestige and the chance to finally shake that past. She could have become the mother of a much needed Duke of York and no matter what Henry looked like, he could still charm and still woo and he treated Katherine with respect. When Katherine ordered her own household appointments and dismissed two of Mary’s maids for impertinence he didn’t countermand her as this was her domain. The investigation which followed dug up Francis Dereham who had followed her to court, but whose role is ambiguous. Katherine claimed he raped her, but he claimed they were promised to each other. Evidence from Katherine’s household and her own contradictions proves that she lied and her relationship with him was consensual, even if he was an obnoxious twit. There appears to be no or little evidence to support the long repeated idea that he had renewed his relationship with Katherine Howard as Queen, although Karen Lindsey argues that Katherine did have sex with both him and Thomas Culpepper as she enjoyed sex and he had followed her in order to claim Katherine as his wife. Francis Dereham was closely questioned but may not have been tortured as he put Thomas Culpepper into the frame. Now Culpepper did have a brief relationship with Katherine before she married Henry and she was pleased to renew this as a friendship afterwards. Henry had a bout of depression in March 1541 and shut the over active Katherine out of his bedroom. It is clear that she became bored and used the opportunity of his visits on errands by the King to renew their time together. It has been said she only continued to see him in an intimate sense because he bribed her. However, she gave him gifts and wrote to him to come when her trusted senior lady, Lady Jane Rochford was about. Katherine didn’t need to go on seeing him at night, she could use her power to get rid of him. There is contradictory evidence as to who was in control of her liaisons while on progress, with the finger being pointed at Lady Rochford, but Katherine could be hard to please and her household state that both she and Lady Rochford used them to find and plan ways to bring Culpepper to her. Although there is evidence that Katherine foolishly met with Culpepper in weird places and late into the night, we don’t have the eye witness or other evidence that she committed adultery that we are often given the impression of in movies.

Katherine is often shown as hysterical when giving her testimony to Cranmer and in the Six Wives, she is deleterious and mad. There is some truth in this as she was very upset and terrified when he came to question her, but probably not to the extent of madness. In fact it was Lady Rochford who went mad. Katherine did weep a lot and was in a terrible and probably hysterical state and it took a lot of time and assurance to get her to talk. She spent her time over the next months between illness, comfort eating, being carefree and bouts of tears. Told she would die she became very frightened and had to be man handled into her barge to go to the Tower. What we have to understand is Katherine was at first promised mercy and then a tearful Henry, having now discovered her presumption of adultery and treason, threatened to kill her himself. Katherine also has to be seen in a world where women were meant to be virtuous maidens and virginal wives and very modest. Katherine was charged with having led a debauched life. This has given life to her presumed reputation. Katherine is wrongly seen as having numerous lovers, were the figure, if we say she is guilty is more like two men before marriage and two, including her husband afterwards. One of these abused her in a modern, but not historic sense and was certainly inappropriate with a very young girl, who was just about old enough to be considered for marriage. One she was promised or married to under canon law and claimed her after her bigamy with the King in his eyes. The other she fell in love or lust with and finally of course she slept with her husband the King. Even if guilty of adultery, this is hardly the activity of a sexual and overly pampered bimbo. If Katherine didn’t commit adultery, then she had a boyfriend, a nuisance and a husband. Again, hardly worthy of the whorish reputation of novels and Hollywood. Not even Anne Boleyn, who was accused of sleeping with half of the English and French courts and adultery with five men and incest with one of them, has now that same reputation. No scholarship has inspected the charges and situation around Anne’s trial and found them to be false. Katherine was not even tried. She was declared guilty by an Act of Parliament in which the allegations are laid out called an Act of Attainder. The ambiguity of Katherine’s meetings with Thomas Culpepper has left us with an unclear picture as to her guilt or innocence which leaves the door open for historians, film makers and fiction writers to interpret her actions any way they wish.

Catherine divides opinion like her tragic cousin Anne, I don’t think she was evil or particularly immoral either, it’s true she has been judged over the centuries by the standards of the ages, the Victorians who liked to portray women as either saints or sinners hid behind a veil of hypocrisy when it came to morality, the upper classes regularly visited brothels and yet demanded the absolute purity from their female relatives, Lacey Baldwin Smith hasn’t much sympathy for Catherine and it’s true in The Tudors she was seen as some kind of sex starved nympho, I remember in the Six Wives Of Henry V111 as soon as she was alone she grabbed one of the servants in her household and pulled him down on top of her, I knew that was just not true, she was sleeping with all the servants, when single and living with her gran she had a light hearted affair with Manox or Derham, I’m not sure if the abuse theory about Manox is correct, we know as soon as girls hit puberty they develop mature feelings and have crushes on boys, Manox was older than her and in her grandmothers employ so he was to blame here for encouraging her, but I doubt really if anything happened between them, perhaps a bit of kissing and cuddling, had they gone all the way then Manox would have committed a serious breach of trust there, and the Howard’s would have been horrified at Catherine’s fall from grace, but I think it could well have been quite harmless then there was Derham who probably was her first love, they called each other husband and wife which in Tudor times was as good as a betrothal, then being the member of a grand house like many young people she was given a place at court and her and Derham had fizzled out, her past should have stayed in the past and it would have but as Henry began to pay court to her she had no choice but to suffer his company and then he seriously wanted to marry her, she did her best to act as a good queen consort, she was attentive to Henry and she amused him with her carefree vivacity, the trouble started when Derham who in the past had also been a pirate coerced his way into her household and this was something she did not want, tv books and films have always shown her as a giggling girl who loved to party, but the majority of girls are then as now, Mary 1st loved fine clothes and jewels it’s a feminine trait, this does not mean she was frivolous, Catherine Parr also was known for her love of luxury, yet she was a Bluestocking! Catherine’s mistake was allowing him into her house and locked to wind her up, she was kind to lady Margaret Pole being locked up in the Tower and sent her parcels of food and warm clothing which shows consideration for another, in a way I feel her reputation has been worse than Anne Boleyns as she has gone down in history as the wife who heated on him and an adulteress wife has always been made out to be a lot worse than she was, Eleanor of Aquitaine’s reputation was held to account when rumours abounded she had slept with her own uncle, according to one writer she was notoriously flighty and said to be wanton, yet she was faithful to Henry 11 all through their married life, it was Henry who deceived her with many women, the Plantaganet’s were a lustful family, Henry 1st fathered it was said thirty bastard children, yet it’s the wives who if they have just one affair are immediately painted as black as can be, Catherine was not a stupid girl she was taught to read and write and could dance, she was a member of one of the most noble houses in the land, it was impressed upon her she would go to court one day and make an equally grand match with another noble house, she was aware when she was queen it was her duty to be at Henrys side and bear him a healthy son, no doubt she found the court entertainments more exciting than her other duties and quite possibly surrounded herself with people her own age, she was attracted to Culpeper who she would have seen now and then who was described as very handsome and could not have helped comparing him to her aged obese and balding husband, she not not have enjoyed sleeping with the King and must have dreaded the nights, when he was infirm or away she no doubt felt very relieved, who instigated the first fatal meeting with Culpeper we do not know but it should have stopped there, i should imagine apart from enjoying the trappings of queenship and all the gifts Henry bestowed upon her, she was very lonely and starved of the physical side of love which people have when they are mutually attracted to each other, having to endure sleeping with Henry who by now was quite repulsive especially to a young woman like Catherine, she yearned for another lover, someone handsome, her own age and in that court where it was teeming with hundreds of people, courtiers noblemen and women, servants court officials, ambassadors etc, she well have thought it would be easy to meet in secret, had she not met with Culpeper and been so foolish in writing him the note which was later found in his apartments, and when questioned had she admitted she had been involved with Derham in the past her life may have been spared, she made several bad decisions, it seemed everyone was out to destroy her and then John Lassells whose sister Mary had been a servant in her grans household decided to write a prim little letter about her unchaste life, Lassells could well have been acting out of pious diaproval but his sister could well have been jealous of Catherine who she had known, Catherine was said to be an attractive girl and quite possibly was sexy a trait which her cousin Anne Boleyn was known to possess, men find that irresistible and women hate that of they don’t possess it themselves, everything then seemed to fall apart, it was sheer bad luck what happened to Catherine I feel, yes she was foolish to meet with Culpeper whether they actually had sex or not is debatable, but I feel they most likely did, having been alone for some hours and being attracted to each other, It would be highly unlikely if they hadn’t, and Catherine could well have been a highly sexed girl, like a pack of cards her world came tumbling down, Derham was questioned after it was found he had known her before, the fact he was at court looked very suspicious, he then implicated Culpeper and then Catherine was kept under guard and her Howard relations were subjected to some grilling, what happened to Henrys fifth queen was tragic yet I feel she does not deserve to be portrayed as the immoral girl she has been, she indulged in a few love affairs when she was single, that does not make her immoral, she was young and naive in thinking she could meet with another man, that does not make her evil but it shows a lack of respect for her husband, she was not having affairs with multiple men which if she was very immoral she would be, I don’t think she was a giggling flibertigibit either which is how she’s always portrayed but just a young slightly bored girl who was married to a man she did not love, I think many writers could be a bit more sympathetic towards Catherine really, she paid the ultimate price and it’s said was not more than eighteen when she died.

Hi Gareth – what fascinating images, Parthenope and Iphigenia: one a siren and the other a princess blood sacrifice to the goddess Artemis. Are you saying that we have these differing reputations to sculpt our impression of the young queen and that we need to look beyond and find the more rounded person behind them?

I think, if I recall correctly, without ever reading much about her, I’d concluded that she was a dippy vamp, cunning, manipulative, and repeating patterns of behaviour learned in the dormitory, when left to her own devices due to Henry’s “problems” (let’s call them). So I tend to agree with you – if that is what you mean.

Great article, Gareth! I had no idea that Catherine Carey was portrayed in The Six Wives…Will have to watch that one. Though you only touched on Cavendish, I was glad of the reminder because it reinforces for me his bias towards the Boleyns. He is much kinder to Catherine Howard, though she and Anne faced similar charges. Jane Boleyn is derided for having “betrayed” her husband and sister-in-law, and then again for doing the opposite and “helping” Catherine. I guess with Cavendish, you just couldn’t win! LBS’s Tudor Tragedy was the first bio I read focusing specifically Catherine. Though it was obvious that LBS thought she was “silly tart,” I sensed a lot of pity from him. There just seems to be something about Catherine that generates that underlying sympathy.

Yes, Catherine Howard was a young impressionable, from noble family and sent to partenal grandmother for guardianship, where her guardian failed to protect her. Catherine was left on her own and made bad choices. These mistakes came back to haunt her which cost her her life. Catherine became another pawn in King Henry’s Court.

Gareth Russell, I have not had the pleasure of reading your books on Catherine Howard, but what I read today on your book “Parthenage and Iphigenia: The Posthumous Reputation of Queen Catherine Howard”, has my interest and will have to purchase one to complete the story.

Amazing article. Poor Catherine Howard.

Amazing Article!!

Cathrine Howard was a poor thing I thing. She married Henry at only 17 years old. What I most like about Cathrine ist the Nickname the King gave her. ‘Rose without a thorn’.

But she betrayed the King so I “Understand” that she got beheaded too.

And again this is an amzing article Garreth:)

Henry VIII never referred to Katherine Howard as his rose without a thorn. That is a myth, demolished by David Starkey. Claire has also written an article about that myth on this website. We also do not know if Katherine was seventeen when she married Henry, she could have been fifteen or sixteen.

Thank you for the article, Gareth. Very interesting–I had no idea so many fictitious works had been written about Catherine…even Dumas’ play! I fear Catherine was really a victim of neglect from her parents. She was sent off to stay with an elderly aunt who obviously had no interest in the girls in her care and was woefully ignorant of the goings-on in her house. Had Catherine a mother to advise her and love her, she may not have looked for love in the arms of callow young men. Her story is sad, tragic really. She wasn’t the brightest bulb in the chandelier to think she could have met with Culpepper without the king ever discovering her liaison. She clearly had no concept of life in the king’s court. And her ignorance cost her her life.

Katherine was young and lived for the moment. She has been portrayed as someone who enjoyed life. She was young and enjoyed being in love. Most people have done silly things when young, she was unlucky to be beheaded for it. Court life was full of pit falls and not everyone survived . It’s a shame she was murdered as we will never know how she would have developed. All very sad and no one knows where her grave is. A wronged Queen.

Hi Margaret, Katherine was buried close to her cousin Anne Boleyn in Saint Peter ad Vincalar in the grounds of the Tower of London. There is a beautiful flagstone to commemorate her and Anne and others buried there, like Margaret Pole and Jane Boleyn, the latter executed and buried at the same time as Katherine. Queen Victoria had them laid. The bones were examined and reburied and placed in sealed boxes and labelled. However, there was some confusion as the pathologist believed that Katherine Howard’s bones had disintegrated, as young bones sometimes do more quickly than older ones. However, Katherine was definitely placed here at the time and there is no record of her being moved. As the levels in floors change over time and graves shift, she could be a little further over. She is somewhere close to Anne but her bones may have crumbled. Very tragic as she was only a young woman as was Lady Jane Grey, another unfortunate young woman, even younger than Katherine. The Tudors expected anyone over 14 to behave as adults and treated them as such, executing people at 14_or 15_or above, if they were found guilty of what they called adult crimes: murder, heresy, serious theft, treason and sometimes adultery if the Queen was involved, although the latter wasn’t a crime by itself. We know today that young people have their brains wired differently and emotional development goes on well beyond 14 or even 18. This world was quite different and young women were considered old enough to marry after 12 and have children after 14, even with men much older than them. To us this would be shocking but to the Tudors it was not abnormal, especially for a second or third marriage as they were desired to have children early. Childbirth was very dangerous and many women died early. It was a horrible thing, plus a woman was her husband’s property and expected to be above reproach. Katherine was such a breath of fresh air, so full of life, cut down before her potential was realized.

Katherine was far too young and naive to understand the enormity of the position that

was required of her as Queen of England.

And I don’t even think she realized at the time that she was soiled goods because she had

given her self to others, also she was so bedazzled by the many gifts from King Henry, that she did not consider the consequences.

\\

She was a young girl not looked after by her Grandmother as she should have. Henry was a sick man in pain due to his leg, a lead type ointment being placed on, and it gave of a very bad smell. This young girl came into this world. Henry was not really able to much in bed. But it seemed he was happy. Yes she was wrong in taking a lover. But was she not talked into it as well. Had she had a child who would have known if it was not Henry’s. As long as the lover was not found out.

Its said that Henry was in the chapel when she was arrested, and she ran away sceaming for Henry.Had she got to him he would have forgiven her.

I’ve always felt that Katherine, much like her predecessors, was a victim of her sex and the times. She was dangled by the Howards to regain the power they lost when Anne Boleyn fell from grace and the Seymours became the clan du jour. She was a baby, really, and not nearly as bright as her dead cousin, Anne, who in the end couldn’t control Henry. She wasn’t docile and amenable like Catherine of Aragon and Jane Seymour, and she was too young and pretty for her own good. And she came into Henry’s life at a time that he was still hale enough to think himself up to the challenge of loving a very young girl, but was fast disintegrating into a decripate old wretch who stank from an ulcerated leg, obesity, and a singular obsession with getting male heirs on his wives. I’ve often thought that she was a silly teenager that was more than likely completely grossed out by the man she was married to, while still possessing all the raging hormones of any girl her age. She would of course find escape in the arms of a pretty young man closer to her in age, if only to block out the horror and disgust of having to consummate her marriage with her odious husband. If he was even able to consummate the marriage at that point. I feel sympathy for her. She was a pawn, and she paid the ultimate price for being young and at the whim of her family’s folly.

I really enjoyed reading everyone’s comments..interesting views.