Thank you to Clare Cherry, co-author of George Boleyn: Tudor Poet, Courtier and Diplomat for writing this guest post on George Cavendish and his poetry, Metrical Visions, which has been used by some historians and authors to paint a rather black picture of George Boleyn.

Thank you to Clare Cherry, co-author of George Boleyn: Tudor Poet, Courtier and Diplomat for writing this guest post on George Cavendish and his poetry, Metrical Visions, which has been used by some historians and authors to paint a rather black picture of George Boleyn.

If you don’t know, George Cavendish was Cardinal Thomas Wolsey’s gentleman usher and was the author of The Life of Cardinal Wolsey and Metrical Visions, poems or laments written in the 1550s about the falls of prominent Tudor people.

Over to Clare…

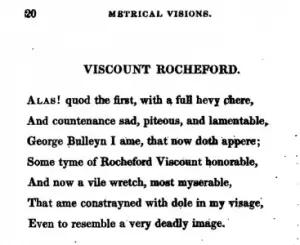

Old George Cavendish seems to have been a puritanical little man, and as a poet he makes you want to slash your wrists. But where would George Boleyn detractors be without him? Lost at sea is my guess. Cavendish adored Cardinal Wolsey and hated the Boleyns and their faction. His Metrical Visions are a set of verses about those who died as traitors during the reigns of Henry VIII and his son (who really was a chip off the old block). He puts words into their mouths, and where it comes to the Boleyns and their friends, who died for sexual offences, he really goes to town in wanton character assassination. He has George Boleyn say:

“My life no chaste, my living besti*l;

I forced widows, maidens I did deflower.

All was one to me, I spared none at all,

My appetite was all women to devour,

My study was both day and hour,

My unlawful lechery how I might it fulfil

Sparing no woman to have on her my will.”

Now let’s get a bit of perspective here. For a start, George didn’t actually say these words; Cavendish did. So when George regurgitates them in works of fiction it would appear that the author has got a bit confused. These words, and George’s scaffold speech in which he admits to being a wretched sinner deserving of death, have led to fanciful theories that he was homosexual, that he raped women and abused his wife. A bit of a stretch you may think, but not for Boleyn haters who will use any old excuse to have us believe they were monsters.

Without Cavendish, I think it highly unlikely George’s scaffold speech would be interpreted in the way it has been. Good old Cavendish! What would Boleyn haters do without him!

Of course, if Cavendish knew that George Boleyn had homosexual relationships and that he was a rapist and wife abuser, then everyone would have known it. Odd it was never mentioned by anyone, whether during George’s lifetime or at his trial, or by enemies following his ignominious death. Strange that. But perhaps that’s a little bit too logical for some writers to grasp.

If we take Cavendish as literally as some people seem to, then George was having sex on an hourly basis. He must have been knackered.

Good old Cavendish goes on to say:

“My lust and my will night in alliance

And my will followed lust in all his desire.

When lust was lusty, will did him advance

To tangle me with lust where my lust did require.

Thus will and hot lust kindled me the fire

Of filthy conscience, my youth yet but green

Spared not my lust presumed to the queen.”

“And for my lewd lust my will is now shent

By whom I was ruled in every motion.” etc etc etc etc….deary me how that man goes on.

But hang on a minute, he’s not having George Boleyn say this. Oh no, he’s talking about “Weston the wanton”, as he so nicely calls twenty-five-year-old courtier, innocent Francis Weston. Actually, in his verses about Francis he mentions ‘lust’ 11 times. Maybe Cavendish was just jealous that everyone was getting something he was missing out on.

As for Anne Boleyn, he has her say, “My life of late has been so abominable” and talks of her “Unjust desires”.

Then he moves his venom onto Jane Boleyn having her say: “Following my lust and filthy pleasure”, and then calling her a “Woman of vice insatiate”.

Is there any evidence that Anne was actually guilty, or that Jane was a lustful wh*re?

No, so Cavendish can’t really be taken seriously as an unbiased, accurate source.

To add to the fun he then goes on with:

“My lusts too frequent, and have by them experience,

Seeking but my lust of unlawful lechery;

So that my wilfulness and shameful trespass,

Doth all my majesty and nobleness deface.”

He also speaks of “Poisoned lecherous offence.”

Is he talking about George, Francis, Anne or Jane?

No, these are his verses about Henry VIII. Is he suggesting with the words “shameful trespass” that the king was a rapist? Highly unlikely, don’t you think? Is he suggesting with the words “unlawful lechery” that the king had homosexual relationships with his courtiers? Again unlikely.

So why do some writers take Cavendish’s verses at face value when he refers to George Boleyn, but not when he writes about Henry VIII?

You don’t suppose it’s out of a cynical desire to paint George Boleyn in a bad light do you, in the same way as Thomas Boleyn and Jane Boleyn have been for centuries? Surely not!

You can read Metrical Visions for yourself at https://archive.org/stream/lifecardinalwol02singgoog#page/n89/mode/2up.

If you’re interested in learning more about George Boleyn then you can watch the “George Boleyn Interviews” playlist of videos on YouTube – click here – and read George Boleyn: Tudor Poet, Courtier and Diplomat.

Great analysis, and isn’t it about high time that novelists – and even some historians – refrained from depicting George as homosexual, or bisexual, or as an aggressive rapist/womaniser when there isn’t the evidence to support any of these portrayals? Unfortunately, some myths will not go away, as can be seen in relation to Edward II and Isabella of France, to Jane Rochford, to Mary Queen of Scots, to Lady Frances Grey… the list goes on.

However, one thing did occur to me while reading this article. Cavendish placed a great deal of emphasis on Katherine Howard’s beauty and lust in his verses on her, and similarly, when he wrote about Thomas Culpeper, the focus was on lust. Now, there are endless contemporary references to Katherine’s attractiveness and Culpeper undoubtedly had a reputation for lechery, whether deserved or not. It was well known that both had died suspected of adultery, whether they in fact ever actually did the deed or not.

Anne Boleyn, we can say with a great deal of certainty, was not guilty of the crimes attributed to her, but she was nonetheless tarnished as a harlot and as an adulteress. Only in Elizabeth’s reign was Anne’s reputation reassessed to a significant extent. But still, she was associated with lust, adultery and wh*redom in the popular imagination, and this association began in her own lifetime on account of her displacement of Katherine of Aragon. The records are full of references to people being arrested or even imprisoned for calling Anne a wh*re, a bawd or a paike (prostitute). So clearly, even before the downfall and execution, her sexual reputation was questioned.

This leads me on to think: even if George Boleyn was neither a rapist nor a homosexual, is it not beyond the bounds of possibility that he was indeed a womaniser? My question is, why would Cavendish have focused so greatly on George’s lust if there was not some substance to it? After all, he emphasised Anne Boleyn’s lust and Katherine Howard’s lust – both died after being found guilty of adultery, whether deserved or not, and Culpeper was painted as an aggressive womaniser. Cavendish also emphasised Katherine’s beauty – we know from other sources that she was indeed very attractive.

You might not agree with Warnicke’s thesis, and I tend not to, but perhaps she does have a point that some, at least, of these men had reputations as womanisers. I am not saying they were guilty of lecherous or ‘unnatural’ practises – there is no evidence for this at all – but perhaps, at a court notorious for its licentiousness, the likes of George and Weston were known for their sexual adventures. Engaging in extramarital sex was, after all, not seen as dishonourable for a well-connected and wealthy gentleman. Cavendish refers to Henry VIII’s ‘lechery’ and that king had several wives and mistresses.

George Boleyn was probably neither homosexual nor bisexual, and there is no evidence that he was a rapist, or even aggressive. But he may very well have engaged in extramarital shenanigans, and it is not our place to judge or condemn an individual living in a very different society almost five hundred years ago. At a court where men regularly engaged in sexual liaisons – Culpeper had several lovers before meeting with Katherine Howard – and where a woman’s reputation was suspected – the Spanish ambassador doubted that Jane Seymour was really a virgin, having been at court for several years by the time Henry’s eye fell on her – it is probable that some, if not all, of the men accused with Anne were known for their sexual adventures. A dark interpretation of these affairs, however, is not supported by the contemporary evidence and such interpretations should be put to one side.

He may well have been a womaniser and had a reputation as a ladies’ man, and that is something that Clare and I say in our biography of George, and Clare is not attempting to argue against that, but, as Clare says here, some historians have gone further than that and accused him of rape and of abusing his wife. If we’re going to accuse George of that basing the theory on this poem then we need to also take into account what the poem says of Henry VIII.

I agree. Chapuy is usually wheeled out when one is looking to criticise Anne, despite his obvious bias in only reporting negative comments/opinions, often by unnamed sources. But unfortunately you have to look elsewhere when trying to paint George in a bad light because Chapuy’s comments are generally favourable towards him, or at least not noticeably unfavourable. To criticise George you have to wheel out Cavendish. George Boleyn was no doubt arrogant, and I don’t doubt he had mistresses like most men of his status, as had the King. But I do find it quite difficult to understand how one verse in one poem by a man who hated the Boleyns can be used to destroy a man’s character and reputation, particularly when there’s no corroborative evidence.

Do you know where I think this all started, though, in recent times – I really think Warnicke’s book set in motion this idea that George was deviant, which then escalated in the realm of popular fiction with “The Other Boleyn Girl” and “The Tudors”. Warnicke’s idea is that none of the five men who were executed with Anne belonged to a faction – she rejects the idea completely – and she asks, there must surely have been something about these men that led to their arrests and executions. If the answer to that question is that they were not actually guilty of adultery with Anne (or incest in her brother’s case), then surely they must have been guilty of something? Because if they were not, then five innocent individuals went to the scaffold.

Warnicke’s book asked some disturbing questions, but it is an academic book and I do not think many people would even have heard of her theories had it not been for “The Other Boleyn Girl”, an incredibly successful bestseller that has, in turn, influenced much fictional writing (and sometimes non-fiction) on the Boleyns. We have seen a stream of copycat novels, with their one-note, harsh portrayal of Anne and increasingly titillating, lecherous portrayals of her family and Henry VIII’s courtiers. Warnicke’s suggestion that some at least of the men executed with Anne were guilty of unnatural practices, unfortunately, proved a very appealing idea to writers of popular fiction, and this later translated onto the screen with “The Tudors”, in which George rapes his wife and has an affair with Smeaton.

I have not read all the recent novels about the Boleyns to know, but I am sure that many now present George as homo- or at least bisexual. But, with Julia Fox’s sympathetic biography, perhaps there will be happier portrayals of his marriage to Jane.

I think you’re right. Prior to Warnicke George was usually treated kindly in fiction and non fiction. It’s only in the last thirty years or so that has changed. It does seem that the demonization of George stems from Warnicke’s theories, which leaves you with the unsavoury suspicion that it’s homophobic in origin. Then Weir twisted it into rape and wife abuse, as did The Tudors and other novelists.

People knock “The Other Boleyn Girl” a lot and much of it is deserved, but the interesting thing is that the portrayal of George really isn’t that terrible (OK, except for the part where he knocks up Anne in order to get the vital heir but that’s Gregory being Gregory). His homosexuality is presented sympathetically; he’s stuck in a situation where he can’t admit whom he really loves and his relationship with his wife is naturally somewhat strained as a result, but while Mary is horrified at finding out about it (realistic enough given the times) she still loves him and keeps the secret for him. In fact, of the books which portray him as *just* gay, most are pretty positive about him. It’s when rape etc start getting thrown in that he becomes Satan’s lackey at court. But yeah, Warnicke definitely started the modern wave; most Georges previously were witty, handsome, heterosexual dudes married to Jane The Shrew.

I have to stick up for Cavendish a bit here, and not *just* because he’s an incredibly valuable source even though you have to sift his words a lot (where else would we have learned anything about Mark Smeaton’s background). He has positive things to say about George as well — he describes him as graceful, “Dame Nature did her part”, gifted and handsome. As you say, there’s nothing implausible about the idea that he got around. But I think that we sometimes get stuck in the idea that the charges against Anne and her “confederates” were so ridiculous that it must have been obvious at the time, but I don’t think that’s true. Consider the number of modern cases where accusations which are retroactively ridiculous are taken seriously and people spend years in prison — the Satanic daycare panic, Sir Roy Meadow’s number-fudging to make it seem like innocent women were guilty of murder, trials with very dubious evidence where someone is convicted because he seems like a jerk and not because there’s legitimate evidence tying him to that particular crime. It’s not hard to believe that people at the time genuinely thought Anne et al were guilty, partly because of the Just World fallacy (“I don’t do that, so it will never happen to me”) and partly because holding a different opinion from someone so all-powerful as Henry VIII would take a tremendous act of will mentally and would also be very dangerous. It would be fatally easy to fall into the mentality of “Well, they must have done something or else they wouldn’t have been condemned.”

I think Cavendish was doing something that is very common even now; projecting what he believes to have been a real crime onto his genuine memories of his youth. If you find out that someone you knew committed some horrific crime after your acquaintance ended, you’ll find all sorts of “signs” that something wasn’t right, and possibly even “remember” sinister incidents which would mean anything had the person not been convicted. He describes Jane Boleyn as having been wanton at court, but he’s writing after her death — was he thinking of how she died and assuming that since she was found guilty of being “a bawd” that her earlier behavior must have been worse than he realized? Similarly, after “learning” that George Boleyn was incestuous, vague memories of George’s earlier affairs may have started looking a lot darker, since after all a man who would commit incest would be willing to do anything.

I would agree with you except that Cavendish later contradicts himself. In his verses about Henry he seems to accept that Anne died due to the King’s love of change, which suggests that he, like Chapuy, was sceptical of the charges and convictions. Yet he is still highly critical of the Boleyns and their friends. In fact he is judgmental of everyone he writes about except Wolsey.

Cavendish wrote the poems over a number of years and according to the edition I have (A.S.G. Edwards edited it) there are signs that he revised things here and there. He may have vacillated back and forth, or he may have believed that both things were true — Henry was sick of Anne, and Anne was sick of Henry and doing unspeakable things. Chapuys at least had the advantage of being a privileged, well-connected foreign national and able to leave the country if things got hot. He had the luxury of being able to form, and communicate, his honest opinion without having to worry excessively; Cavendish didn’t have that.

Considering his love for Wolsey, and what happened to him, it’s not surprising that he saw everyone in court as repellent. But I can’t accept that he’s responsible for all the smearing of George Boleyn; first of all, despite what other commenters are saying, he NEVER says George was homosexual, that came from later, highly dubious interpretations of both this and George’s speech on the scaffold. Secondly, the big proponent of George the Rapist is Alison Weir, and yes, she did seize on “I forced widows” etc. But come on, you’ve seen what Weir did with Queen Isabella and Hugh Despenser, with Jane Grey and Dudley, and probably a few others I’m forgetting. She ALWAYS jumps to rape as an explanation for why a woman didn’t like a man, and the two examples I cited didn’t have so much as a contemporary sentence fragment to support them. If the Metrical Visions didn’t exist, do you really think she would have made a calm, unbiased evaluation of what George Boleyn’s relationship with his wife and other women was like? Weir is the real problem here, not Cavendish.

“Puritanical” seems a bit harsh; by our standards, every single person living in sixteenth-century England was puritanical or at least espoused standards of behavior that would seem absurdly strict these days. Cavendish would hardly have been alone in deploring the courtiers’ supposed behavior. Also, he appears to have been an old-school Catholic who didn’t like the church reforms — very unlike the Puritans, who thought the reforms didn’t go nearly far enough.

Hi Sonetka, see my response to Esther below. I’m not blaming Cavendish for the ridiculous interpretations of his poems by Warnicke and Weir. That is not what I say in the above article at all. I’m just making the point that they are used as the so called evidence for George being a gay wife abusing rapist, by twisting the meaning.

I agree puritanical is harsh, but no harsher than Cavendish’s horrible language. Bearing in mind Wolsey had an illegitimate child I find him rather hypocritical when calling people besti*l for having extra marital affairs.

Clare…I heart you ♡.

I’m working on an article for History Today about the Rochford marriage…debunking Cavendish and his nonsense is half the article, haha.

I think it is unfair to blame Cavendish (“puritanical”, “going in for character assassination”) because of the way historians and fiction writers take his poetry. We criticize historian George Bernard because he takes seriously a poem that indicates Anne Boleyn might have been guilty, but I haven’t read anything slamming the poet. Cavendish is in the same boat as Carles (Bernanrd’s poet), in that both of them are much safer by writing on the assumption that the people beheaded by Henry deserved it.

Furthermore, I doubt that Cavendish’s poem played that big a role in the negativity about George. I would hope that writers would eventually want a good motive to account for Jane Boleyn’s allegedly lying her husband and sister in law onto the scaffold … and an abusive George provides one, whereas the usual things l(Jane is jealous the relationship) are simply insufficient (IMO)

I’ve read a lot of older works which have Jane Boleyn being the one who’s promiscuous and wants to get the noble George out of the way by getting him killed (and losing most of her income and her social position with him, though that’s seldom mentioned). Quite a few of them also read backwards from the time of her death, when she was said to be insane, and make her irrational or at least very over-emotional even when she’s just starting out with George. Some very Protestant writers made her a crypto-Catholic willing to do anything to bring him down. I’m not saying these were convincing characterizations; Jane was a dreadful, hard-to-believe character to work with especially before Julia Fox’s book, but for a lot of writers “She hated him, so she wanted him dead” really was enough. I have to wonder, though, even if Cavendish’s poem had never existed (or, more accurately speaking, if Alison Weir hadn’t decided to highlight those lines) would writers have started hypothesizing about abusive behavior anyway? The last twenty years have seen a lot more emphasis on marital abuse and writers and historians are creatures of their time; they’ll look in the present for explanations of the past. But like you, I don’t blame Cavendish. I think he may have genuinely believed what he was writing and he has good, or at least illuminating, things to say about these people, most of whom he knew at least fleetingly.

I agree that Cavendish’s poetry is abusive and judgmental towards everyone, not just George. However, it is his poetry that is used as the sole ‘evidence’ to suggest George was homosexual, a rapist and abusive to his wife. I don’t blame him for the ridiculous interpretations of his poems. I’m just pointing out that it is due to his poems that George’s character is interpreted the way it is. It is used as an excuse to demonise him by those who choose to do so while ignoring his verses on, for instance, Henry. I do, however, think that Cavendish is puritanical. He is certainly highly judgmental

Even if George Boleyn liked women and had a few sexual affairs, and I say, if..that doesn’t mean he forced them, abused or raped them…it means he was a cad, a womanizer, but probably not to the extent above. Was George Cavendish himself gay? He is so obsessed with the subject, you would think he hoped that they were gay and his brain has gone into overdrive.

Cavendish is a great source for Wolsey’s life and Anne’s earlier life. However, he was dedicated to his old master so must have been delighted to see those who may have contributed to the Cardinals death get their comeuppance. His words hit out at the entire crowd, King included..this is his way of getting his own back for everything he imagines has gone wrong with his universe. His words are very insulting, but it is also his obsession and it raises questions about what is in his own overtaxed mind.

As others have said, the problem with his verses is that they are fiction, but they have been interpreted by writers of fiction, film and even some historians as being said by Boleyn and the others. When some take the actions in the verses too far and portray them as fact, especially if they are well known and respected authors, their theories are seen as fact, but the truth gets destroyed and forgotten. Ideas about George Boleyn’s sexuality, Anne Boleyn and her brother, her personality, long debunked are now fresh in the eyes of a new generation of readers. I am all for exploring the accusations against Anne and George or even their own ideas, but falsehoods should not be pushed as true. There is some great fiction out there, but there is a lot of misinformation. As long as you know fiction is fiction, it is entertainment. These verses probably found an audience in the taverns of their day…entertainment and nonsense.

I don’t know if Cavendish was gay but he does NOT say that any of the men he writes about were gay; that was Warnicke’s and later Weir’s extremely dubious interpretations of phrases which were about general sexual immorality (also George’s scaffold speech where he, in the convention of the time, says that he’s a sinner who deserves death for his misdeeds). It really isn’t fair to knock on Cavendish because writers four centuries later misinterpreted him.

I am not knocking Cavendish, I am asking questions about how he was interpreted and making the same point as everyone else that his poems are an attack on the Boleyn faction and the King and Queen, not what George and the other men actually said. I am also making the point that as his verses belong in the taverns and are not to be taken as a serious reflection of the lives of the people they attack, so the fictional interpretation of them belongs to the world of fiction, not history.

Georges character has been maligned like his sister and the incest charge I feel was the most awful of them all, he is described as a young ‘Adonis’ which means he was easy on the eye and no doubt was a flirt and loved women the way Anne loved the company of men, this makes them normal not sexual deviants, there is no record of any love affairs he indulged in but at court there would have been ample opportunity and he possibly was a bit of a womaniser in my experience most men are! And they were no different 500 years ago, apart from the fact religion played a part in their lives more than it does today, Cavendish was an enemy of the Boleyns and painted a very black picture of them just like Sander about 50 years later, critics do not present a fair judgement and I cannot understand why so many writers including Warnicke take his verses seriously, I think Warnickes theory that George and Anne were guilty of incest and that George committed buggery and was homosexual are frankly just too ridiculous for words, ever since their fall from fame the Boleyns name has been linked to infidelity incest, sexual deviancy and conspiracy to murder, it was all a plot to bring down Henrys second queen and that’s why I cannot understand why Cavendish’s poems are taken so seriously, George’s scaffold speech ( the wretched sinner remark) has been interpreted as someone who committed immorality and besti*lity yet really on the scaffold men and woman do admit their ‘sins’s as they call them but it does not mean they were actually guilty of the dread offences they were accused of, it was traditional of them to make a scaffold speech and confess and praise the King, criticism of the King was taken as an offence and their assets could be seized meaning their families left behind would suffer, at her speech Anne spoke of Henry as being ‘a most gentle sovereign lord’ but she’d daren’t say anything different she had to think of her parents who might suffer the consequences if she spoke ill of him, George’s wretched sinner remark possibly just meant he hadn’t been as religiously minded as he ought to have been, maybe he should have attended church more, he also made an unkind remark about the princess Mary when her mother died saying it was a pity she didn’t join her, he could have gambled a lot and drank a lot, maybe he had affairs with married women, he is said to have left a bastard son behind but little is known of him, save he was named George also, the theory that his wife accused him of incest is rather difficult as there’s no reliable source for it and the rape of his wife, that was in The Tudors which although entertaining to watch was a load of rubbish historically it was a complete travesty of the truth, George Boleyn like his sister was far from being a saint yet they were not the monsters of legend, his reputation like that of his sister has suffered greatly, it is upto us in our more enlightened age to give these tragic people the benefit of the doubt, and not take at face value some slanderous poems written by a sworn enemy of theirs, they suffered the most dreadful accusations 500 years ago and paid the ultimate price, their reputations were in the mud they were stripped of their honours and Annes daughter branded a bastard, some even thought she wasn’t even Henrys, it is very difficult to get rid of rumours and mud sticks, let us take Cavendish’s poems as what they really are, just a load of vitriolic nonsense written by a person determined to blacken the names of these already maligned victims.

Hi Christine and may I congratulate you on an excellent and very insightful analysis. George Boleyn has been maligned even more than Anne, possibly. These verses are horrendously insulting and the way they have been interpreted even worse. Modern authors should know better, as many of these myths have been debunked, but they seem to relish in using the more scandalous sources, rather than what contemporary reports show, what someone actually said, wrote, their friends and families wrote etc and adding their own wild imagination, these authors like Gregory and Mantel present a fictitious scenario that they claim is true. Mantel sells Wolfe Hall because she did ‘five years of research ‘ which she says covered the sources, which she probably did, but then appears to have disregarded most of it, which is why we get another skewed portrait of the Boleyns, More and everyone else. Funny thing is our two ladies Clare and Clare have also done years of research looking at many of the same sources and come up with a totally authentic and balanced view of Anne and George Boleyn…one that tells us they were scholars, linquists, translated books, intelligent, good looking, yes, fun loving and good at dancing and music, ambitious yes, but focued on reforms and change, generous, bold, excellent at sports, very well educated, had character flaws yes, but they were not vicious or rapists or abusers. Cavendish may not be entirely to blame for the way he is interpreted, but if he didn’t write rubbish to begin with, there would be nothing to interpret. Cavendish saw a chance to destroy the reputation of the Boleyn family with these verses, and took it, because with their fall his words just may not be taken as treason. It’s far more likely that they became tittle tattle in the taverns than anything else, but with these authors they have become mainstream and television has taken this nonsense and put these stories out into the wider world, running with them. So Anne and George, regardless of the truth, are maligned all over again. It’s also a fact that some authors attempted to re educate the public and write authentic balanced accounts, contradictory to the nonsense of Sanders quite early on. Unfortunately, some like Fox, who presented Anne as a saint and martyr, went too far the other way. Agnes Strickland attempted to rescue the Queens from obscurity and by the Victorian age Friedman and others were writing in detail on her political and other influences in proper biographies. Anne and George have been rehabilitated by Ives and many modern writers, but Warnicke turned the clock back turning George back into a sexual predictor. Now I don’t care if he was a homosexual, but I do care that there is no evidence to substantiate this claim. If he was a womanizer, he was a womanizer; yes, it is not good, but what evidence? What I do object to are depictions of him as a rapist and abuser, especially as this is not true. The reputation of these very clever and influential people has suffered enough. We don’t need Hollywood and fiction repeating this rubbish over and over again. I agree with your assessment, Christine, let’s treat this poem as tavern garbage.

Thank you Banditqueen, yes it certainly does annoy me when these writers who are supposed to be educated people are taken in by rubbish like this, Anne sadly miscarried her last child and the poor little mite itself hasn’t even escaped the abuse which its mother and uncle was subject to, fifty years later Sander wrote Anne brought forth a shapeless mass of flesh – in other words he was implying it was a deformed monster, this what Warnicke believes as she has the theory it’s what contributed to the belief that Anne was a witch, and guilty of incest as sexually depraved women were thought to give birth to deformed babies, it’s all utter nonsense as Anne was never accused of witchcraft it wasn’t in any of the charges against her. yet Warnicke places too much emphasis on Sander and thinks Annes last baby really was deformed, in reality I bet the poor little thing was beautiful.

Can I just jump to Warnicke’s defence here – I don’t think she came up with her theories to be controversial, or to malign any of the men accused with Anne, including George. Having read her work, I don’t believe her intention was to portray George as a sexual predator. I think, essentially, she disagreed with Ives’ factional interpretation of Anne Boleyn’s downfall; with some justice, I think, because Ives’ theory has several problems with it. The biggest problem is his suggestion that Cromwell actually masterminded Anne’s downfall, an idea that has also been taken up by Weir. I find this theory very unconvincing – Henry was in control of Anne’s disgrace, not Cromwell.

Having disagreed with Ives, and disagreeing with historians such as Bernard that Anne actually was guilty of some, if not all, of the charges, Warnicke seems to have asked herself, what did cause Anne’s downfall? If it wasn’t faction, and if it wasn’t Anne’s guilt being discovered, then what was it? And she pinpointed the January 1536 miscarriage, which was followed by Anne’s execution only four months later.

Now, I do not agree with Warnicke, because there is no evidence for a deformed foetus and this theory requires reading the sources in a very speculative way. But, as I suggested in an earlier post, she did raise an interesting question of why it was that these five men in particular were targeted. They did not belong to a Boleyn faction, they were not all associated with one another and one or two, such as Brereton, were not associated with Anne at all. I disagree with her that some at least of these men were known for engaging in sexual pastimes that were condemned at the time, but I think she is right to suggest that they might have had reputations for sexual excess. The focus, of course, was on Anne – in accusing her of adultery with five men, one her own brother, the aim was to portray her as a monster of lust. Only one man was necessary for Katherine Howard to be convicted and ruined (and later Dereham); but in Anne’s case, five were involved in order to blacken her reputation forever.

The thing is Cromwell himself admitted later after all six were dead that he had gone home and thought the whole thing up, I believe what really happened was that Henry sick and tired of Anne and being in love with Jane Seymour or thought he was, or just desperate to sire another male heir told Cromwell to get rid of her and possibly by any means, much the same language he no doubt used when he was tied to Anne Of Cleves, Weir suggests that Cromwell must have had his blessing else he would not have dared to move against her, there was no signs earlier in the year he was seeking to put her from him and a journey to France had been planned, also Henry had engineered a meeting between her and Chapyus whilst at chapel, much to the latters disgust, a sure sign he was supporting his queen even though rumours abounded they were hardly on speaking terms, it all happened so quickly rather like the shocking execution of the old Countess of Salisbury that many people believed then as they do today that something sinister was afoot, Anne and her alleged lovers were discarded the way an old pair of slippers are, thrown into the bin and forgotten about, I think Warnicke does place too much emphasis on Cavendish and Sander though, she may not as you say AB be trying to be controversial and again why should these five men be targeted? Well I believe personally they could have been the best looking men at court, I know this sounds shallow but I doubt Cromwell would have had the rather flirty Anne connected to the elderly member of her household or the Kings, the charges had to be convincing and so these men who after all were all young and fit and often passed the time in her household, Norris and Weston for example, Norris was engaged to her cousin so he was often in the queens company as his fiancée was one of her ladies in waiting, and had been involved in the banter with Anne when she made that most foolish remark about ‘dead men’s shoes’, that made him a victim even though he was a close friend of Henry so these two were chosen as scapegoats, why Brereton was chosen is a mystery he was a bit older than the others yet he was involved with dealings in the north which one source says displeased Cromwell therefore he could well have been targeted because of that, the unfortunate Smeaton was very young and good looking and made the confession which dropped them all in it, he could have had undue pressure put on him, Cromwell hadnt risen to be Henrys chief minister by being gentle, he was unscrupulous and he was fighting for his position at court, the queen was openly his enemy and he had seen her finish Wolsley, he wasn’t going to allow that to happen to him, so I believe he terrified the poor boy and made him confess to something which never happened, he promised him no harm would come to him and he would suffer the more merciful death by beheading, it is significant that none of Annes lovers admitted to adultery on the scaffold except Smeaton, as for George being chosen, obviously the more revolting Anne appeared the easier it became for Henry to get rid of her, he would garner more sympathy than condemnation, what is a mystery is what did he himself think, did he really believe she had deceived him and was congratulating himself and Cromwell for discovering the truth, he no longer cared for her yet once he had loved her so passionately he had split the country in two so it’s only natural he would feel intense rage hurt and jealousy or did he know deep down she was innocent and if she was innocent so were the others, and because they had all been found guilty he as monarch and head of the justice in his country had to see the sentences were carried out, the law decreed they were traitors and had to die but how did he himself feel, he offered Norris a pardon if he would admit his guilt was he saying to him, ‘ I want to get rid of my queen and I need your admittance that you were lovers but I promise you will go free if you do so’? Norris said no he could not confess to adultery with the queen as it was not true, which enraged Henry yet in normal circumstances a man would be happy if he found out his best friend and wife were not carrying on behind his back if there were rumours circulating around and or someone, (as Smeaton did) actually admit he had, Henrys behaviour is not normal and so it all adds up to there being a coup, a plot to bring down his second queen, it was vile and inhuman yet throughout history and it happens today, if you are a threat to the country you are ‘disposed of’.

I know this started out as a discussion on propaganda by Cavendish (and let’s be clear folks, what he wrote was not history – it was the yellow journalism of its day), but let’s get back to dumping – or not dumping – on Warnicke, who seems to be a favorite target of some folks.

Warnicke is a problematic historian from my point of view, especially with the Rochfords and Anne Boleyn. Some of her conclusions are speculation but to her credit, if you know how academic history is written, you almost always know where she got her info and how she made her conclusions. She’s not as rigorous with citations as this retired hard scientist would like but historians aren’t as anal about that sort of thing as they are in my field of research – that’s a general complaint of mine when it comes to almost all historical writing, academic or “popular.” I’m not real happy with her book on Anne Boleyn but I have always been able to figure out the basis of her arguments because if you know how to read academic writing, you can almost always follow her thought process. I find other stuff she has done much more satisfying, like her papers on Fisher and Morley and her historiography (NOT history) work _The Wicked Women of Tudor England_. There’s a reason she’s a respected professor with tenure with a good reputation in the gender studies end of the history field.

Part of the problem here is the disconnect between the norms of historical writing by academics for other academics – which is what Warnicke writes – and “popular history” which is what people like Weir write. You can tell right off the bat which is which if you know what to look for. For example, in Weir’s _Lady in the Tower_, look at the references. Let’s pick on Weir stating that Francis Bryon visited Lord Morley in the run up to the plot to do in Anne Boleyn. Her citation for this is merely “L&P.” This is not to academic standards but to the non-discerning eye, it looks like she’s done her homework – but she hasn’t proven that at all since it is impossible to trace where she got her information of Bryan visiting Morley. This is insufficient citation and it’s bad form. Even for an undergraduate senior thesis, Weir would get thumps for that level of shoddy citation.

Now let’s look at Warnicke. Specifically, let’s look at the infamous _Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn_. Let’s go to something I disagree with her about: Chapter 7 “Harem Politics”, p. 176, citation 32, referring to the statement Warnicke makes over the non-secrecy of Anne miscarriage and how Hall reporting it in his chronicle was a sign that this was an important herald of Anne’s downfall (with inferrences about the secrecy of other miscarriages). I really have issues with this conclusion on several levels – but that’s not my point here. My point is that when you go to endnote 32, you find Warnicke citing the calendar of state papers on Spain, vol. II, #113; a book _Miscarriages_ by Dewhurst, p. 50; and Hall’s chronicle, vol. II, p. 266 of the edition she lists elsewhere in her Bibliography. Yes, I disagree with her point but after looking up her references behind her statement, I know why she made that conclusion. Now that’s excellent citation and good academic form for a historian. Warnicke almost always let’s her readers know what info she used to make her conclusions. Fellow academics know this and respect her for her demonstrated foundation in “the literature” of her field and her use of primary sources, even when they don’t agree with her conclusions.

But Weir generally writes for the non-academic audience that buys her books whereas Warnicke is writing for a smaller but much more critical primary audience of research types. By writing about Anne Boleyn, she gains a secondary audience of non-academic readers, some of whom don’t understand the conventions of academic writing and thereby don’t grok the speculative nature of a historian’s conclusions.

I’m not saying I like a lot of her conclusions in her Anne Boleyn book but I respect her as a historian.

Let’s go one step further. I have nothing against “popular” historians that do their homework, unlike some academic historians I know (who look down their noses at “amateurs”). A good example of an excellent, non-academic “popular” historian is Claire. She does her homework and she cites her sources with the anal-retentive thoroughness of a hard scientist writing for peer-review. You always know where Claire is coming from because like Warnicke, she almost always tells you.

In response specifically to AB, I must quibble just a little. Warnicke tells her readers exactly how she got to the deformed fetus conclusion and it makes sense in the framework of her rather complex but well-argued chapter 8 “Sexual Heresy,” right there at the top of p. 302. Warnicke’s problem is that other people jumped on her conclusions and ran with them out context. It’s a problem with academic writing overall, i.e. writing for a small audience of fellow-researchers, oblivious to what non-critical thinkers outside academe may react. It’s right up there with California falling into the sea and our impending doom everytime there’s an earthquake swarm at Super-Killer-Volcano Yellowstone and the threat of extinction from SARS (remember SARS, folks? Oh, how soon they forget…)

Okay, I’ll behave and get off my soapbox for now…

Feel free to stay on your soapbox, Doc, I’m on mine most of the time!

I do have problems with Warnicke’s book and her reliance on certain sources, but, as you point out, at least a reader can find out exactly what sge bases her theories on because she is excellent at referencing. Weir drives me mad with her references, or lack of them, as it is so hard to track down what her source is when she just puts something like “LP” and there are so many volumes in the archive and so many documents in each volume. I’ve also found that the document she is referring to is not always in the source she states so it really is a nightmare. For me, as a researcher, the notes and bibliographies of books are as important as the text itself because I like to check references and form my own views based on those. I get very cross when a historian or author makes a statement and then there’s no reference, particularly when it’s a rather sweeping statement.

Thank you for the kind words!

I agree. Whatever problems I have with Warnicke bleed into insignificance compared to failure to reference work in order to gloss over inadequate research.

In my opinion, you should choose either to reference or not to reference. There really isn’t any point in half doing the job. If you’ve gone to the trouble of adding footnotes/end of chapter notes, bibliography etc. then it seems odd not to put in the full reference. Why not “LP x. 902” rather than “LP”? It’s really odd as they’re on separate lines in the Notes section so it’s not as if it takes up any extra room. So frustrating!

Then again, why would you put in the full reference when you haven’t quoted it correctly? Not giving the correct reference makes it easier to hide the fact that you’ve made it up!

True…

Clare I have to disagree that the notion of this book is “terrifying”, Warnicke may have devised a theory about George Boleyn that you disagree with, but that does not subsequently invalidate all of her other work. She is a very well respected historian with years of experience and has written books about Anne of Cleves and Mary Queen of Scots and has researched many interesting individuals such as Anne Stanhope, Alice and Jane More, and Lettice Knollys. The only academic biography of Elizabeth of York that I can think of is the one by Arlene Okerlund. There has been one very brief academic book about Jane Seymour and an excellent biography of Katherine Parr by Susan James. For most of the wives, we have narrative, popular accounts that repeat the same tired old stories. I think Warnicke will have many interesting insights about these women.

Speaking of Warnicke, as I have just notified Claire, according to the Palgrave Macmillan website, she is publishing a new book about Elizabeth of York and Henry VIII’s six wives. It sounds fascinating.

Sounds terrifying!

It’s the interesting insights which terrify me.

Clare, can I ask if you mean that in relation to any figures in particular. I am most interested in her views on Elizabeth of York, especially given recent interest in the first Tudor queen. I imagine her arguments about Anne Boleyn and Anne of Cleves will be roughly the same as those covered in previous books.

Apologies but I just feel I have to defend Warnicke sometimes because people love to attack her work, but I don’t think her arguments are any less feasible than those offered by other historians. Lacey Baldwin Smith wrote a fascinating study of the historiography of Anne Boleyn, published by Amberley, and he essentially made the point that Warnicke’s theories have been highly criticised by other historians, but these historians put forward theories regarding Anne’s downfall that are just as problematic. Baldwin Smith pointed out that Warnicke relies on one key piece of evidence (Chapuys) for her theory, but Ives also relies essentially on Chapuys and Bernard relies mainly on the French embassy.

I, personally, found her arguments about Katherine Howard and Mary Queen of Scots convincing, and her research is exhaustive. She does not take evidence at face value, which is something a lot of writers today do. I also appreciated her analysis of Anne Boleyn’s character and appearance – she showed that there is no reliable whatsoever that Anne had any deformities, or even the beginning of a nail on her finger.

Warnicke had an interesting insight that all the men who were accused with Anne were homosexual. Evidence? None. She had an interesting insight that Catherine Howard was abused by every man she ever met and was blackmailed by Thomas Culpepper. Evidence? None, as has been eloquently pointed out by Gareth Russell. She had an interesting insight that Anne’s fall came because of her last miscarriage of a monster. Evidence? Sander, nothing else. Her interesting insights are nothing more than interesting hunches. So any interesting insights she may come up with tend to fill me with dread. It has recently been suggested that Anne Boleyn had a close relationship with her sister-in -law. Does that mean they were lesbians? Anne was called ‘the goggle eyed wh*re’. Maybe the goggle eyes meant she was an alien. Interesting insights or daft conclusions? If Warnicke’s insights are academic then I prefer none academic rational use of extant sources to the academic abuse of extant sources to try and prove a hunch. She’s no worse than Weir or Bernard, but that’s no defence. Anyone can pluck an ‘insight’ out of thin air. That’s why I have such huge issues with her. Sorry but I just don’t trust her work.

Clare, that’s fair enough, I personally find her theories about Anne Boleyn to be more interesting and well-argued than Bernard’s or Denny’s, for example. I have not read her book about Anne of Cleves but I will do so, as it has largely had good reviews. Her biography of Mary Queen of Scots was also excellent, I would recommend it.

The problem with academia for the sake of academia is that anybody can come up with any theory based on any vague and unsubstantiated interpretation of any evidence. I’m not sure I find anything to admire in that however well they reference the unsubstantiated interpretations.

I was always taught to reference correctly….then even if you don’t agree with everything…and its good if you don’t, as long as you can present you ideas clearly and precisely, backed up with evidence, proper references….and mine were often some of the hardest to find, it does not matter that people don’t agree with you they can find the source and know what you are arguing has a basis. I respect all historians and scientists who reference their work well. I get very frustrated myself when I can’t find more information based on something in a biography, even a good one, especially if its a theory I am not familiar with. It’s even more annoying when decent historians don’t reference or have a bibliography at all. If numerous sources are cited and quoted from, it is very unhelpful not to fully list and reference those sources for further research. Professor Warnicke does at least extensively reference her work. She is well respected and her histography and analysis is excellent, even if you don’t accept all of her theories.

What’s really interesting is when two historians with very different views can both use primary sources to back up their views – one of the things I love about history!

One of my pet hates is sweeping statements without a source being cited or a viewpoint being presented as if it’s a fact.

Warnicke gave a source for Mark Smeaton ‘probably’ being George Boleyn’s lover because George once lent him a satirical book on marriage. Irrespective of the fact she gave a source I still thing that is a massively sweeping statement!

And we know the very same book was passed around a group of courtiers, including Thomas Wyatt.

I think what makes a good historian is being unbiased about your subject as its all too easy to make excuses for his or her behaviour and actions if you personally are in thrall to the them.

I think you have to feel a certain amount of passion for your subject. For example, Eric Ives wrote in his biography that Anne Boleyn was the third woman in his life after his wife and daughter, and when I heard him speak his passion for her as a subject was clear. I know I’m passionate about the Boleyns but I feel that I can also be balanced. I think your work works across as dead if you don’t feel something for the person you’re writing about. A book like a biography is a huge commitment and you need something to drive you, something about your subject to keep you going.

Too true you have to have a genuine interest in your subject, i also read the remark Ives wrote about Anne and that was his second biography of her, his first one being written years earlier, he has got rave reviews for his biography on Anne, I liked Weirs ‘ The lady in the tower’ as it was about the last months of Annes life and I thought her execution was very detailed, I know people do complain about her lack of references but I find her books very well written, I’m no academic so am not using her books for research else it may well be a problem, I’m just a history lover and find it a wonderful pastime.

Conor, Claire has told me that the Cleves book is very good. I don’t mean to come across all Warnicke bashing in that none of her work is worth reading. That would be very wrong. I know you respect her so we’ll agree to disagree. But yes, Bernard wasn’t terribly convincing, and as for Denny she was very biased in Anne’s favour.

The Daily Mail didn’t give Denny very good reviews on her Anne Boleyn biography, their book critic said that she was quite scathing in her anti Catholic comments and too critical of Katherine Of Aragon, the critic also went on to write that if the reader wants to know about Anne Boleyn it was best to read Eric Ives wonderful book.

How can we say that Warnicke’s theories are merely “interesting hunches”? You could say that about any historian. Her theories about Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard are as valid as those offered by other writers, despite the criticisms you voiced earlier.

I don’t think the sexual heresy argument is a valid theory at all. It is not backed up by any evidence. For example, if we are to believe that Smeaton and George were gay because they both read the same satire on marriage then so was Wyatt as he wrote in the book too.