Our views and opinions of George Boleyn, Lord Rochford, are often coloured by depictions of him in series like “The Tudors”, and movies and books like “The Other Boleyn Girl”, but was Anne Boleyn’s brother really a bisexual, or even homosexual man, who raped his wife and had affairs with young men? Was he the depraved libertine of Retha Warnicke’s “The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn” who was linked to sodomy, besti*lity and other such “abominable” acts? Did he commit incest with his sister Anne Boleyn to help her provide Henry VIII with an heir to the throne or was he actually something else entirely?

Today, I’m going to look at George Boleyn’s background and how he rose to be one of the most powerful and influential men at Henry VIII’s court, before, in part 2, I look at how his world came crashing down and he was executed as a traitor on 17th May 1536.

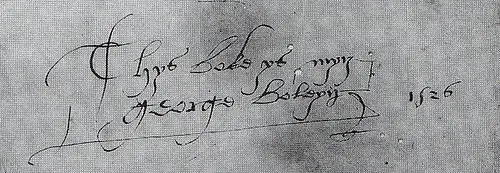

- “Thys boke ys myne, George Boleyn 1526” – George’s signature inside a book

The Boleyn Family

Josephine Wilkinson, author of “The Early Loves of Anne Boleyn”, writes of how Anne Boleyn was born in early summer 1500 or 1501, a second daughter to Thomas Boleyn and Elizabeth Howard who already had a daughter, Mary. Thomas and Elizabeth went on to have at least three sons, Henry, Thomas and George, but it was only George who survived childhood. It is generally thought that he was born around 1504, making him around three years younger than Anne.

According to Wilkinson, while his sisters were probably educated together at home, at Hever Castle in Kent, George went to Oxford to be educated before joining the court of Henry VIII to follow in his father’s footsteps as a diplomat and courtier. Eric Ives also writes of how George was probably a product of Oxford University and that as well as carrying out diplomatic duties he was also a recognised court poet. Ives writes of how we know that George played in a mummery in the Christmas revels of Christmas 1514-1515, so must have been a child at that time, and then went on to become a royal page. Ives states that by 1525 George was married and that by the end of1529, he had risen to become a member of the King’s privy chamber. There is a remark made by Jean du Bellay in 1529 implying that he thought George was too young to be sent to France as ambassador and, if we take 1504 as his birthdate, 25 may have been seen as rather too young for this type of position, but then George’s family was in high favour with the King at this time, the King being besotted with Anne Boleyn.

Career and Life at Court

George Boleyn enjoyed a high profile career at court. Here are some of the positions and grants he was given during his time at court:-

- 1522 – In April 1522 George and his father, Thomas, were given “various offices, in survivorship, in the manor, honor and town of Tunbridge, the manors of Brasted and Pensherst, and the parks of Pensherst, Northlegh and Northlaundes, Kent; with various fees and power to lease” (LP 3. 2214). It has been suggested that this may have been an 18th birthday present for George

- 1524 – In July 1524, according to the Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, “Geo. Boleyn. Grant of the manor of Grymston, Norfolk, lately held by Sir Thos. Lovell. Westm., 2 July” (LP 3. 2214).

- 1525 – Appointed as a gentleman of the King’s privy chamber but lost this position just 6 months later when Wolsey reorganised the King’s court and weeded out those he didn’t like and trust.

- 1526 – In January 1526, George was appointed as Royal Cupbearer.

- 1528 – A letter from Henry VIII to Anne Boleyn tells us that George contracted sweating sickness while at Waltham Abbey with the King and Catherine of Aragon. In the letters, Henry assures Anne of her brother’s recovery, he was one of the lucky ones. Henry writes: “For when we were at Walton, two ushers, two valets de chambres and your brother, master-treasurer, fell ill, but are now quite well. (Love Letters of Henry VIII to Anne Boleyn page xxv, Fredonia Books).

- 1528 – The Letters and Papers record “George Bulleyn, squire of the body” and in the same year he was also made Master of the King’s Buckhounds.

- November 1528 – The Letters and Papers record another grant for George Boleyn: “Geo. Bulleyn, squire of the Body. To be keeper of the palace of Beaulieu, alias the manor and mansion of Newhall, Essex; gardener or keeper of the garden and orchard of Newhall; warrener or keeper of the warren in the said manor or lordship; keeper of the wardrobe in the said palace or manor in Newhall, Dorhame, Walkefare Hall and Powers, Essex; with certain daily fees in each office, and the power of leasing the said manor, lands, &c. for his lifetime. Del. Westm., 15 Nov. 20 Hen. VIII” (LP 4. 4993 Grants in November 1528).

- 1st February 1529 – The Letters and Papers record “For GEORGE BULLEYN – To be chief steward of the honor of Beaulieu, Essex, and of all possessions which are annexed by authority of Parliament or otherwise, and keeper of the New Park there, in the manor of Newehall; with 10l. a year for the former, and 3d. a day for the latter; vice William Cary.Del. Westm., 1 Feb. 20 Hen. VIII.” (LP 4. 5248). He was later granted a life interest in Beaulieu.

- 27th July 1529 – Another grant is recorded in the Letters and Papers: “27. Geo. Bulleyn, squire of the body. To be governor of the hospital of St. Mary of Bethlem, near Bishopesgate, London. Del. Westm., 27 July 21 Hen. VIII.” (LP 4. 5815).

- October 1529 – A letter written by Chapuys to Charles V states how Chapuys was escorted to the King by a gentleman named Poller/Bollen (thought to be Boleyn). (LP 4. 6026)

- December 1529 – In Letters and Papers there is record of “Instructions to George Boleyn, gentleman of the Privy Chamber, and John Stokesley, D.D., sent to the French king” telling them to consult with Sir Francis Bryan on their arrival at the French Court.(LP iv 6073). The mission of George and Stokesley’s diplomatic visits to France were to encourage support for the King’s divorce from Catherine of Aragon.

- December 1529 – In the list of peers (LP 4. 6083), it says “Sir Th. Boleyn as visc. Rochford” and then later (LP 4. 6085) “For THOS. VISCOUNT ROCHEFORD, K.G. – Charter, granting, in tail male, the title of earl of Wiltshire in England, with an annuity of 20l. out of the issues of Wilts and Devon; and the title of earl of Ormond in Ireland, with an annuity of 10l. out of the farm of the city of Waterford. (fn. 4) Witnesses: W. archbishop of Canterbury, Thos. duke of Norfolk, treasurer of England, and Chas. duke of Suffolk, marshal of England; Thos. marquis of Dorset, and Hen. marquis of Exeter; John earl of Oxford, chamberlain of England, and Geo. earl of Shrewsbury, steward of the Household; Arthur viscount Lysle, William lord Sands, the King’s chamberlain, George lord Bergavenny, Sir William Fitzwilliam, treasurer of the Household, and Sir Henry Guldeford, comptroller of the Household, and others. York Place, 8 Dec. 21 Hen. VIII. Del. Westm., 8 Dec.” This made George Boleyn Lord Rochford.

- 5th February 1533 – Letters and Papers record that George Boleyn was summoned to Parliament:”Fiat for writs of summons as follows :—i. Geo. Boleyn, lord Rocheford, to be present in Parliament this Wednesday. Westm., 5 Feb. 24 Hen. VIII.” (LP 4. 123) and it is noted that his attendance rate was higher than many others and shows how committed he was to Henry’s new Reformation Parliament. He was very influential in parliament and it is also noted that his views on religious reforms and curbing the Pope’s powers in England earned him many enemies and that one such man, Lord LaWarr was on the jury which found him guilty at his trial in May 1536.

- March 1533 – George, Viscount Rochford, was sent to France to present King Francis I with letters from Henry VIII, “written in the King’s own hand” informing the French king of his marriage to Anne Boleyn and encouraging his support for this marriage (LP 5. 230). Henry VIII enclosed a letter that he proposed that Francis should write to the Pope, urging him to support the divorce. George was successful in this mission.

- May-August 1533 – George travelled to France again on an embassy with the Duke of Norfolk, his uncle, to be present at a meeting that was supposed to take place between the Pope and Francis I. It was while he was in France that he learned that the Pope had excommunicated Henry so he returned to England to give this news to the King. (LP 6. 556, 692, 918, 954)

- April 1534 – George sent to France again with instructions to encourage Francis I’s support for Henry’s cause. (LP 7. 470)

- June 1534 – Letters and Papers state: “George lord Rocheford. To be constable of Dover Castle and warden of the Cinque Ports. Del. Westm., 23 June 26 Hen. VIII.” (LP 7. 922) These were the highest honours that could be bestowed on a man by the King and George took these appointments very seriously.A letter from George to Cromwell on 26th November 1534 shows George’s anger at Cromwell undermining orders that he made as Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. (LP, 7. 1478)

- July 1534 – George sent to France yet again with instructions to rearrange the meeting between Anne, Henry and Francis I due to Anne’s pregnancy and her not wishing to travel in that state. (LP 7. 958)

- May 1535 – George’s final diplomatic mission to France. The purpose of this visit was to negotiate a marriage contract between Princess Elizabeth and the third son of the King of France. (LP 8. 663, 666, 726, 909)

- May 1535 – A letter from Eustace Chapuys in the Calendar of State Papers (Spanish) shows that George, his father and the dukes of Norfolk and Richmond were present at the executions of 3 Carthusian monks who, like Sir Thomas More, had refused to swear allegiance to the Acts of Supremacy and Succession.

- 1st July 1535 – In Letters and Papers, George, Lord Rochford, is named as one of the commissioners at the special sessions of oyer and terminer set up to try Sir Thomas More (LP 8.974).

The numerous mentions of George Boleyn, Lord Rochford, in The Privy Purse Expenses of Henry VIII, show what favour and high regard the King held him in. We know that from these records that George accompanied the King shooting and played bowls, dice, cards and other such games with him.

George, Poetry and Religion

As well as being an influential man at Parliament and having an impressive diplomatic career, George was also a well known and talented court poet, although I have been unable to find copies of his poems. Like his sister, Anne Boleyn, he loved poetry and the arts was committed to religious reform and was highly intelligent and educated. He translated two Lutheran religious texts from French to English for his sister, dedicating them “To the right honourable lady, the Lady Marchiness of Pembroke, her most loving and friendly brother sendeth greetings” and it was George who encouraged Anne to share reformist writings with the King.

Personal Life

Personal Life

George Boleyn married Jane Parker, daughter of Henry Parker, the 10th Baron Morley, and his wife Alice St John, in around 1525. In January 1526, a note in Cardinal Wolsey’s hand confirms that “the young Boleyn and his wife” were given the sum of £20 and Alison Weir writes in “The Six Wives of Henry VIII” of how the couple were given Grimston Manor in Norfolk by the King as a wedding present.

There is much speculation about the Rochford marriage with the traditional view being that the marriage was unhappy. In “The Tudors”, we see George’s disdain for his wife and Jane’s resentment and jealousy of George’s relationship with Anne, and this would explain why she allegedly gave evidence against them at their trials, accusing them of incest.

But, is this true? Was it a loveless marriage?

It is hard to say and I don’t think we will ever know the truth.

I haven’t read Julia Fox’s book on Jane Parker, but allegedly she challenges the notion that it was a loveless marriage and instead argues that it was happy and romantic, and that there is no reason to believe otherwise. Alison Weeir believes that Fox is “overstating her case” and that it was unhappy and that “sadly for romantics, the surviving evidence convincingly shows that Jane did testify to her husband having committed incest with his sister, and that she also confided to her interrogators some highly sensitive – and probably false – information.”

Weir believes that the marriage may well have “foundered early on” and that the fact that George possessed Lefevre’s satire on women and marriage, “Les Lamentations de Matheolous”, perhaps speaks of his own views on women and marriage. Weir also wonders if Rochford subjected his wife to “sexual practices that outraged her”, e.g. buggery, and even though the rumours of George having a homosexual affair with Mark Smeaton are likely to be untrue, George may well have practised acts that were not seen as normal. Weir also writes that it may be significant that George and Jane’s marriage was childless and that George Boleyn, Dean of Lichfield during the reign of Elizabeth I, was likely to have been an illegitimate son of George’s, rather than a son of Jane. The fact that George had an affair with a woman seems to go against Retha Warnicke’s view that George was homosexual. The Dean could, of course, have just been a Boleyn relative.

In George Cavendish’s “Metrical Visions”, Cavendish writes of George:-

“I forced widows, maidens I did deflower.

All was one to me, I spared none at all,

My appetite was all women to devour

My study was both day and hour.”

which suggests that George was a womaniser, rather than someone known for buggery and illegal acts.

So, who was George?

Well, no real evidence points to him being a “libertine”, and I would sum him up as:-

- A fervent religious reformer

- A poet and lover of the Arts

- An accomplished diplomat and politician

- A man who, like many other courtiers, took advantage of his position at court and enjoyed affairs with women at court

- A man who enjoyed his high position at court and who threw himself into his work

- A man who was close to his sister and enjoyed spending time with her and with others who shared their beliefs and passions

What do you think?

Sources

- Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII – Found online at British History Online

- Calendar of State Papers, Spain – Found online at British History Online

- The Privy Purse Expenses of King Henry the Eighth, from November 1529, to December 1532 edited by Nicholas Harris – available online at Internet Archives

- “The Lady in the Tower” by Alison Weir

- “The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn” by Eric Ives

- “The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn” by Retha Warnicke

- “The Early Loves of Anne Boleyn” by Josephine Wilkinson

- “Jane Boleyn: The True Story of the Infamous Lady Rochford” by Julia Fox

News

Just to let you know that I’ve added 8 new pairs of earrings to our luxury jewellery site – Opulence – and we also have French hoods and brass rubbings of Tudor characters for sale in our Anne Boleyn Files shop.