On 21st April 1509, at 11pm, King Henry VII, founder of the Tudor dynasty, died at Richmond Palace. He had ruled for over twenty-three years, since defeating Richard III and his troops at the Battle of Bosworth in August 1485. Click here to read about his death.

On 21st April 1509, at 11pm, King Henry VII, founder of the Tudor dynasty, died at Richmond Palace. He had ruled for over twenty-three years, since defeating Richard III and his troops at the Battle of Bosworth in August 1485. Click here to read about his death.

Henry VII’s death was kept secret for a couple of days and then it was announced to the Knights of the Garter on 23rd April at their annual St George’s Day Feast before being made public on 24th April. On 27th April, the Spanish envoy Gutierre Gómez de Fuensalida reported Henry VII’s death, saying: “Henry VII’s death is now public knowledge because Henry VIII is in the Tower and has proclaimed a general pardon. He has released many prisoners and arrested all those responsible for the bribery and tyranny of his father’s reign. The people are very happy and few tears are being shed for Henry VII. Instead, people are as joyful as if they had been released from prison.”1

The new king who was bringing joy to the realm was Henry VII’s seventeen-year-old son, King Henry VIII. William, Lord Mountjoy, wrote to Desiderius Erasmus, the renowned humanist and scholar, about Henry VIII’s accession:

“I have no fear, my Erasmus, but when you heard that our Prince, now Henry the Eighth, whom we may well call our Octavius, had succeeded to his father’s throne, all your melancholy left you at once. For what may you not promise yourself from a Prince, with whose extraordinary and almost divine character you are well acquainted, and to whom you are not only known but intimate, having received from him (as few others have) a letter traced with his own fingers? But when you know what a hero he now shows himself, how wisely he behaves, what a lover he is of justice and goodness, what affection he bears to the learned, I will venture to swear that you will need no wings to make you fly to behold this new and auspicious star.

Oh, my Erasmus, if you could see how all the world here is rejoicing in the possession of so great a Prince, how his life is all their desire, you could not contain your tears for joy. The heavens laugh, the earth exults, all things are full of milk, of honey and of nectar! Avarice is expelled the country. Liberality scatters wealth with bounteous hand. Our King does not desire gold or gems or precious metals, but virtue, glory, immortality […]”2

And, yes, these words are describing King Henry VIII!

As I said in my article from last year, in 1509 “Henry VIII was strapping lad of 6’3, he was handsome, he was well-educated, he was intelligent, he was charming, he was athletic, he loved music and poetry, he was a knight who loved jousting and he desired “virtue, glory [and] immortality”. It is little wonder that the people of England were “joyful” and that there was so much hope for his reign.

In a survey carried out by the Historical Writers Association (HWA) in 2015, Henry VIII was voted the worst monarch in history with words such as “obsessive”, “syphilitic” [sigh!] and a “self-indulgent wife murderer and tyrant” being used to described him.3 Yet, in the same year, author Andrew Grimson picked his “Top 11 monarchs in British history” for BBC History Magazine’s website, History Extra, and included Henry VIII in his list, explaining “although he degenerated from a Renaissance prince into a tyrant, casting off wives and servants with merciless finality, he did make England independent.”4 In 2007, in a debate for English Heritage, Alison Weir argued the case of Henry VIII being England’s greatest monarch, describing him as ” A true child of the Renaissance – a gentleman in the knightly, chivalric sense, an intellectual who read St Thomas Aquinas for pleasure, an expert linguist, a humanist, an astronomer, a world-class sportsman, a competent musician and composer, an accomplished horseman, and a knowledgeable theologian” and stating that “Henry’s true greatness lay in his practical aptitude, his acute political perception, and in the self-restraint that enabled him to confine – within limits acceptable to his people – an insatiable appetite for power.”5 You can read the rest of her argument, which includes a list of his achievements at England’s greatest monarch is…

So what do you think of Henry VIII? Was he a great king? Was he a tyrant? Were there, in fact, “two Henrys”, as David Starkey once said: the young Renaissance king and the older tyrant? Please do share your thoughts on this iconic king.

Notes and Sources

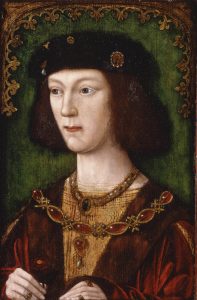

Image: Henry VIII, earliest surviving portrait, c. 1509-13, English School, Berger Collection, Denver Art Museum.

- Starkey, David (2008) Henry: Virtuous Prince, p264, citing Correspondencia de Fuensalida, 517. You can read Fuensalida’s letter in the original Spanish in Correspondencia de Gutierre Gomez de Fuensalida, embajador en Alemania, Flandes é Inglaterra (1496-1509) Publicada por el duque de Berwick y de Alba, conde de Siruela at https://archive.org/, p.515-517.

- Mumby, Frank Arthur (1913) The Youth of Henry VIII: A Narrative in Contemporary Letters. Reprint. London: Forgotten Books, 2013. p. 126-7. See http://www.forgottenbooks.com/

- Flood, Alison (2015) “Henry VIII voted worst monarch in history”, The Guardian, 2nd September 2105. See http://www.theguardian.com/

- Grimson, Andrew (2015) “Top 11 monarchs in British History”, http://www.historyextra.com/

- “England’s greatest monarch is…”, BBC News, 8 August 2007, see http://news.bbc.co.uk/

I don’t believe anyone is good or bad – people are more complex than that. However the change in Henry is remarkable over time. One theory is the jousting accident during his marriage to Anne Boleyn – a major head trauma is known to change people’s personalities…

A Monarchs main responsibility is to his people; to do everything in his power to ensure the safety of the realm. Henry failed miserably in his responsibilities to his people. His treatment of Catherine of Aragon put England at risk of war with Spain. He was incapable of maintaining any foreign alliance, which left England in a precarious position. His policies, his break with Rome, and his own egotistic, selfish, shallow hypocrisy resulted in the deaths of thousands of his own subjects. So, even setting aside his tyranny, I do not think he was a successful King.

I totally agree, Clare – though I am a bit less harsh to him.

He broke with Rome, but not because he wanted to, but because he was obliged under private circumstances.

When Erasmus accused princes following their own lusts and greediness, he felt uneasy at once and it does show something of him, I guess.

I want to add that by then alliances were very frail from each part (France, Saint Empire and so on); I know that cynism has to do with the job but I agree with you : KH lacked personal qualities to be a great man, he could not become a great sovereign.

He despised his father for having been so cautious with public funds (it did not matter for himself who considered it was his own money rather, his action against Church was due to his want of money, he spent in many doubtful ventures, worse than Francis I himselfin this regard)

Hi everybody, lively recalling of the hopes raised by KH’s accession.

As I expressed about another post, I am loath to admit him as a great king.

Though I aknowledge he already had by then a chief quality for a sovereign – that is dissimulation (very useful according to Machiavel)

As a royal heir, he had concealed to his father his greed of power itself, as well as – of course – his hatred towards Dudley and Empson.

When – very soon after – Erasmus had his “In Praise of Folly” published (it was in France), it was too obvious an attack against The Church AND PRINCES ‘excess(even though Erasmus denied the fact : but philosophers are so naive sometimes, ignoring that it is not what they want to establish that matters, but what it can reveal in a sovereign’s intentions), not to be hidden from view.

So, I guess this book was too successful to be ignored and I tend to think it can explain why Erasmus was no more granted hearing by KH by then.

However, Erasmus left England for this reason.

Protector of thinkers – but as long as they won’t disclose his own political schemes …

His good friend More should have suspected his own fate by then – but he wouldn’t.

But oddly enough, John Colet, whose vehemence was directed only towards Church and priests, was granted an absolute protection from this young and “well-disposed” king.

More should have suspected his own fate by then – but he wouldn’t.

There are still a lot of facts showing that, in my opinion at least, KH was a cynical man from the beginning of his reign, and not the kind one who would have been changed into a tyrant later

So, I stop in 1511 (in fear my comment be too long again, not a lack of argument).

But no, I don’t see his reign as a great one, the only fact that he can claim in his own right being “Anglicanism” (he did not intend to go so far)

Historians are divided over whether Henry was a good king, he treated his people harshly over the risings in the north and risked civil war when he broke with Rome, he did build up the navy which lay the foundation of the British Empire, and he freed England from the yoke of Papal authority setting up her own church, if you consider these actions he was great but then his desire for a son led to his six not very successful marriages and led to one wife being judicially murdered, he had also squandered most of his fathers fortune as he was obsessed with going to war with France as he did see himself as another Henry V, the people were taxed over those inane wars and also the Field Of The Cloth Of Gold where again the poor people had to cover the cost, that was when Henry was much younger and had to be seen to act like a King, hence the outward displays of kingship which does cost money, he was affable and people loved him, he was not called the golden prince for nothing, he was popular and such a contrast to his stingy dour father yet it was Henry V11 who had built up the treasury and left England a stable land for his son to inherit, when Henry V111 died in 1547 he left a country divided with religious turmoil a treasury much depleted and a young lad not yet in his teens as it’s ruler, Henry no doubt saw himself as a great ruler yet he was aware he only left a boy as his heir instead of the many sons he hoped he would have, in this sense maybe he saw himself as a failure, one historian thought he was a hero, another as the rarest man that ever lived, personally I don’t see Henry as a great king, a strong one yes, a unique king amongst the many we have had, and although he wouldn’t like it, Henry today is remembered not really for his achievements but more for his six wives, especially the second and the fifth.

What defines a great king? I don’t know. But what I see as Henry VIII’s measuring stick for his kingship is the principle of “needs must”. His needs, that is. His need to be seen as a strong leader lead to his going to war, his cynical and deceitful treatment of the leaders of the Pilgrimage of Grace, and his treatment of those who opposed him, no matter how well they had served him (Wolsey, More, Cromwell, etc). And his need for a son, leading to his callous treatment of his wives. And his self-righteousness, his self-indulgence, his self-pity, his unstable temper. And then: his talents and intelligence, which he could never make use of in full for all the other stuff overshadowing it. So I wouldn’t call him the greatest king of England, but certainly the most interesting one! (And that’s not counting his daughter Elizabeth…)

Hello Claire,

Love your insightful questions; Henry VIII was not a successful King simply because any successes he had were erased through his own downward spiral of severe and harsh treatments to his subjects, friends and family members. The real life horror of his reign lives on in history no matter how much joy and brightness the young Prince and newly crowned King started with.

When you study all the Kings England has had the most successful ones that come to mind are Henry 1st who was so intelligent he was called ‘Beauclerc’ and is remembered for being a fair and just monarch, his grandson Henry 11 was a great king and is called the greatest of the Plantagenets, he built up an empire known as the Angevin empire which was larger than France itself, he also was responsible for changing the structure of the legal system by establishing trial by jury which ensures defendants get a fair trial, another successful King was Henry V who is immortalised in Shakespeare’s play for his wonderful victory against the French, though he left England the weakest King she has ever had in his son and heir Henry V1, Henry V111 is unique in his six marriages but he wasn’t as successful as his predecessors apart from cutting all ties from the Pope and making himself and his successors Head Of The Church Of England, however his tyranny and dreadful deaths of his two wives one being just an immature girl override his achievements, though we have to be fair in that he may have suffered a personality change after his jousting accident there was no need to put to death a young girl who was thrust into the kings path by her ambitious family and who was totally unsuited to be Queen in the first place, who was too young to respect her position as consort to the monarch and gave into temptation all too easily, Henrys greatest achievement I think was in his daughter Elizabeth who kept England great by doing exactly the opposite of what her infamous father did, never marrying.!

Thank you so much Christine for this historical “comparative synthesis”.

Judith Green seems to be less enthusiastic about Henry I’s personal qualities.

Some rebel norman lords (Luc de La Barre, Geoffroi de Tourville and Odoard DuPin) had to suffer his unusual harshness – though I’d rather think that all the Conqueror’s sons were built on one pattern (being as pugnacious as their father).

And , for Catherine Howard’s sake, thank you again.

Without being feminist myself, I tend to see that indeed KH’s main interest and political legacy lies in his queen-daughters.

Very subjectively, I am fascinated by his two first wives, not by the king himself.

Catherine can be seen as conservative, Anne as more liberal, modern.

Just a matter of ircumstances ?

I rather see it as a real reflect of their true person.

Hi Bruno Henry 1st could be very harsh it’s true, in fact the early Norman kings had to be, having not had the English crown for long in their grasp and having to quell rebellions from the vanquished English from time to time, I’m like you in that I really only find Katherine Of Aragon and Anne Boleyn interesting, the two of them with Henry were engaged in some kind of ménage a trois they were really very alike in that they were as stubborn as each other and would not give way, Henry was caught between the pair of them for seven years and after Katherine’s death and Anne’s hasty execution to me it seems like a storm had passed and there were calm waters again, Jane and the wives who followed did not make much of an impact to me and although no doubt they were quite possibly interesting creatures in their own right they never appeared half as interesting as Anne and Katherine, the only impact Jane made was dying in childbirth, Anne Of Cleve’s for being divorced within a month of her marriage( I think) and poor Catherine Howard for being the second Queen to be beheaded and as for Katherine Parr, although she was an intelligent woman and had several books published she’s really only famous for being the one wife who survived him.

Hi Christine, you are just spoiling me with your comments and explanations !

I need to say that I did not intend to show any lack of respect to the different wives of “our KH” – I don’t know if you feel like me, or is it that I was born in the same country as Joan of Arc,I feel like I could hear them, their characters seem so near (thanks to this site and the readrs’ comments) ?

No, I am aware that the last one, Catherine Parr, was a much interesting person, instead .

I find she made four very unlike weddings.

The first does not count (at a historical level), her father-in-law appeared as a very unpleasent greybeard.

The second was of higher-rank much more matching her views (I don’t mean her taste for power, of which we know nothing, but her greed of culture, and especially on theological matters, is well known).

The third uncovered the very capable and well-balanced queen consort we know

The fourth was unluckily shortened, quite a paradox for a surviving wife of KH and then, more free than ever in her own choices it seems (by the way and as you know Anne of Cleves was the “other survivor”, but who cares and who cared already by then?) – she might have realized the rake she had married (when he dared “pay court” – to put it in soft terms – to the teenager orphan Elizabeth) .

And she died so soon after, not being given time to enjoy an enviable widowhood

Ménage à trois seems to me a better word than love triangle indeed- and it is not a matter of it is a french term, or that it might (or not) ring a bell by me, but that the three engaged did not bring the same feelings in this state of things.

Catherine, sure of her legitimacy, and willing to fight for her princess-daughter’s rights (and maybe for keeping the man she used to be in love with) .

Anne, sure of her charm and of her impact on the king – and much disappointed by her former suitors’ intentions – would try her luck as hard as possible ; she was learned, less “classic” at any rate than an aging spanish-born queen – and, just an assumption of me, his royal suitor had made her some promises in order to catch her “heart” – mmm – and she was determined to have him keep them.

Henry, loving nobody but himself, surely often changed his mind by then.

Two strong-willed ladies – and a schism

Only one great King of England, Claudio Ranieri..

When Henry came to the throne he was not yet eighteen years old and he did show of course the promise of a new and vigerous reign and of a King with grace, who was tall and handsome, appeared to be benevelant and was very popular. Henry did show the promise of being a great King, he had everything going for him, he was a true patron of the arts, he had the best scholars, Italian artists and architects at his court, he was a good sportsman, he was easy going and at first he actually did listen to good advice. He had ambitions to expand his claims abroad, a popular, if expensive move, his choice of wife was a perfect move; Katherine of Aragon was the perfect partner for him. She was independent, intelligent, beautiful, came from the famous Spanish dynasty of Aragon and Castile, was herself a warrior queen, protecting England while Henry was playing at warrior in France, saving the Kingdom from Scottish invasion, she was very popular and beloved by the English people, she was his equal and for twenty years he loved her. But the couple also suffered several tragic losses of male and female children, with only one beloved daughter, Mary living and growing up; which transformed their marriage and Henry from a promising great King into a tyrant.

Henry had the makings of a great King; he was an intelligent and a clever King but his personal life, his personal tragic marriages and his inability to produce a son and heir, stifled that greatness by his own insecurity. He dragged his country and first wife through seven years of a bitter divorce because he fell in love and lust with Anne Boleyn who promised him that long lost son, and because he was desperate for such a son. Katherine, sadly, could no longer provide Henry with any more children, but she believed that it was God’s will as an annointed Queen and the mother of the girl she saw as Herny’s rightful heir, Mary, for her to remain married to Henry and to fight for those rights. Katherine argued the marriage was lawful and thus it went on. These years took up time and resources that Henry could have put to better use had he been content and had an heir come along. These years cannot have failed to have changed Henry emotionally either.

Again and again, Henry’s failure to succeed in his personal life stiffled his ability to become a great King. Henry’s second marriage to Anne gave him a second chance and his movements towards making England a more independent nation could have sent him on a better path, but he became jealously obsessive over Anne and also saw everything that happened as a repeat of his marriage to Katherine, in that Anne tragically lost two or three children, one of whom was most certainly a son also. Henry did not give this second marriage the chance that he should have done and was also a fool in the way that he acted while Anne was pregnant. Given that Anne had already lost at least one other child, possibly two, why would Henry risk giving her the anxiety and stress that could lead to a miscarriage by jousting and having another woman on his knee in her apartments, where she could catch them? In 1535 Henry and Anne appeared to be happy and by the end of their progress Anne was carrying Henry’s son, the heir that could have made a lot of difference. Anne sadly lost that child because show off Henry fell in a joust and then looked for sympathy from a pretty face. But he had started this period wih many political and religious changes that could have led to Henry achievments being realized and recognized. His next move let him down and left him bitter and insecure.

After Henry was injured in the jousting accident everything changed. He would never be the same King ever again. Anne lost the potential heir and this pushed Henry further down the road to paranoid insecurity. He acted as if Anne was his enemy, instead of the woman that he had chased and turned everything upside down to marry for seven years, the woman that had been at his side for the last three years, whom he had claimed to love more than life itself. Henry had set aside advisors, councillors, friends, churchmen, anyone who had questioned or failed him, now he was setting aside his wife, again. He may have improved national security, built our fleet and defences, he may have made better laws, he may even have secured our trade, but he was again putting everything at risk with another domestic breakdown. Anne was the victim of all his insecurity and lack of trust; this time he allowed Cromwell and others to plot her downfall and he consented and had a hand in setting her up for trial and execution. Anne and five men of the court were handed over to the wolves and killed. Henry may or may not have believed that Anne was guilty, but whatever his personal feelings he acted because it was convenient, not because it was true. A great King and a secure man does not act in this foolish and dangerous manner.

After the execution of Anne Boleyn it is clear that Henry had a very much split personality. Some of his greatest achievments followed in the last decade of his reign: the Great Bible for example and some of his finest buildings followed, but he also destroyed the monastries. Our iconic images of Henry are from this era; his control of how he wished to be seen is evident in those images. His expansion of Hampton Court and his building of Nonsuch Palace date from the late 1530s. The costal defences also date mostly from the 1530s onwards. The expansion of the freeports and his refounding of the schools also dates from the 1530s. Trade expansion and his mapping of England and abroad also date from this period. His desire to succeed in France brought him temporary glory in 1544 and he also had success in Scotland and established a new social contract and enfrancisement for Wales. But his domestic disasters also grew more quickly and more often after 1540. In 1536-37 Henry was also faced with the most dangerous threat to his crown, the Pilgrimage of Grace. He did not have the field resources to fight the rebels, so he used deception and cleverness to defeat them. He was determined to put down this rebellion fiercely and made threats to enslave or to execute the rebels and their families if they did not submit. In the end, after two pardons, one of which was broken and a second rebellion, a fraction of those 30-50 thousand who actually rose were executed, some 230 in Yorkshire and about 100 in Lincolnshire and elsewhere in total. This may seem like a cruel reaction, and indeed it is, but it is nothing compared with the numbers that his daughter Elizabeth executed after the Northern Rebellion in 1569 and 1570 when over 700 were officially executed and thousands more died in prison. Neither is it anywhere near the numbers killed by the British Empire in Ireland and India in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries or during the wars of religion on the continent. Even Martin Luther caused the death of over 25,000 Protestants in 1525 when he asked the Emperor to intervene against the German peasants.

Henry Viii time and time again lost or gave up the opportunity to act with true greatness. There are signs in his early years that he could do this when he chose, like the pardoning of over 500 rioters after the Prentice Boys revolt in London May Day 1517. In his first two decades he could show mercy and justice and good judgment and he could take advice. He built and he created and he performed for the masses. He was charming and he was benevelant. He showed every sign of being a great and a wise King, but he failed due to many factors. His domestic episodes and emotional insecurity, his almost obsessive love and passion for Anne Boleyn, his need and desire for a son, his allowance of himself to be wrongly influenced by others, his failure to work at his marriage with Anne and to preserve with that marriage longer; his dependance on one prime minister to the exclusion of all others, leading to a disasterour fourth marriage and the consequential immature fifth marriage; his accident in 1536 and as with all monarchs of the time, his lack of long term vision and his parania at the end of his life. Henry was clever in his handling of the fellow monarchs abroad, playing Charles and Francis off against each other; his lack of long term alliances was not short sighted; it was because England needed to stand alone, to grow and because she did not have a base abroad from which to strike when those alliances went south. Henry made alliances to suit England and his needs at the time; this was not always the best thing to do, but it kept his rivals on their toes. This was often the way he balanced the factions in the court. Henry was his own man. He may not have been a great King; but he was a clever one in many ways; he was certainly better for England than most of his predecessors.

Henry started off well as a Prince of the Renaissance but when he turned from his queen he changed. All the beheadings in his reign and his treatment of Catherine and Mary were truly disgusting. But his reign was interesting due to his many wives, breaking with Rome, his building work, intrigue at court and the navy. The best thing he did was give England a great queen his daughter Elizabeth.