On 20th April 1534, prominent citizens of London were required to swear the “Oath of the Act of Succession”. Chronicler and Windsor Herald Charles Wriothesley recorded:

On 20th April 1534, prominent citizens of London were required to swear the “Oath of the Act of Succession”. Chronicler and Windsor Herald Charles Wriothesley recorded:

“all the craftes in London were called to their halls, and there were sworne on a booke to be true to Queene Anne and to beleeve and take her for lawfull wife of the Kinge and rightfull Queene of Englande, and utterlie to thincke the Ladie Marie, daughter to the Kinge by Queene Katherin, but as a bastarde, and thus to doe without any scrupulositie of conscience; allso all the curates and priestes in London and thoroweout Englande were allso sworne before the Lord of Canterburie and other Bishopps; and allso all countries in Englande were sworne in lykewise, everie man in the shires and townes were they dwelled.”

On the very same day, Elizabeth Barton, known as “the Nun of Kent” or “the Holy Maid of Kent”, was hanged at Tyburn with others, including her spiritual adviser, Father Edward Bocking, Richard Risby, Warden of the Observant Friary at Canterbury, and Hugh Rich, Warden of the Observant Friary at Richmond. They had been found guilty of treason by a bill of attainder following Barton’s prophecies against the king’s annulment. Barton had prophesied that if the king went ahead with the annulment and his marriage to Anne Boleyn then he would lose his kingdom within a month and “should die a villain’s death”. Charles Wriothesley recorded their hangings:

“This yeare, the 20th day of Aprill, beinge Mundaye, 1534, the Holie Maide of Kent, beinge a nun of Canterburie, two munckes of Canterburie of Christes Churche, one of them called Doctor Bockinge, two gray freeres observantes, and a priest, were drawne from the Tower of London to Tiburn, and there hanged and after cutt downe and their heades smitten of, and two of their heades were sett on London Bridge, and the other fower at diverse gates of the cittie.”

Click here to read more about Elizabeth Barton.

Notes and Sources

- Wriothesley, Charles, A chronicle of England during the reigns of the Tudors, from A.D. 1485 to 1559 Volume 1, printed for the Camden Society, 1875, p.24.

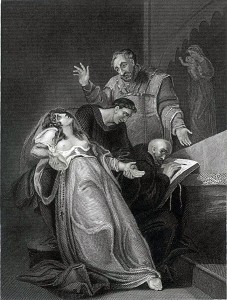

Image: Engraving of Elizabeth Barton. It is thought to be by Thomas Holloway based on a painting by Henry Tresham, and comes from David Hume’s History of England (1793–1806).