Last night was the final episode in the wonderful BBC4 series “Illuminations: The Private Lives of Kings”, in which Dr Janina Ramirez examined illuminated manuscripts from the royal collection in the British Library, and last night it was on the 15th and 16th centuries – yay!

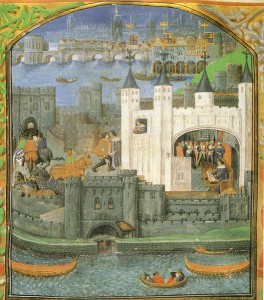

The programme opened with Ramirez looking at a beautiful illustration from an illuminated manuscript of poems written by Charles, Duke of Orléans, when he was imprisoned in the Tower of London after the Battle of Agincourt. You can see the illustration here and Ramirez commented that it was the first topographically accurate picture of London.

Ramirez then spoke of how William Caxton began printing in England in 1476 but that the advent of printing did not mean the death of handwritten books, it just meant that they became more of an exclusive, luxury item for the elite and for royalty. Edward IV was a collector of illuminated manuscripts and commissioned around 50, which are now housed in the British Library. Ramirez explained that although books were being produced in English, French was still the language favoured by the ruling classes and illuminated manuscripts at this time were “histories”. She examined a picture of Vincent de Beauvais – see http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=43440 sitting at a desk writing, while surrounded by books on display, and spoke of how images like that mirrored Edward IV’s library and his love of books. He had a library at his favourite palace, Eltham, where he kept his beautiful illuminated manuscripts which were part of the “props” of the monarchy, the trappings. Edward IV had to rebuild the monarchy after the disastrous reign of Henry VI so his Great Hall at Eltham, with its tapestries, acted as a stage of monarchy, a statement of magnificence, and his collection of beautiful books added to this image.

Edward IV was forced into finding a new source for illuminated manuscripts, now that England did not have vast French territories, and Ramirez explained how he turned to Bruges, the city which he knew from his time in exile. Ramirez examined illustrations by Giovanni Boccaaccio and commented on their realism, a style which set Bruges apart and showed that it was firmly in the Renaissance. In one image of Fortune appearing to Boccaccio – see http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=37420, the reader can see Bruges through the window and door, and Ramirez explained that Renaissance art was beginning to influence illuminated manuscripts. Illustrations were beginning to look real, landscapes like those of the artist van Eyck were appearing in manuscripts and images of birds and animals in the margins were actually scientific observations now. It was a new style.

Ramirez then explained how Edward IV’s death led to the War of the Roses erupting again until it was settled at the Battle of Bosworth Field when Henry Tudor defeated Richard III. She explained that Henry VII’s claim to the throne was weak in that it was through the female line and also through an illegitimate ancestor, so Henry’s mission for his illuminated manuscripts was to emphasise his right to rule, his legitimacy and his nobility. She looked at his use of symbols in an illuminated manuscript – the red dragon of Cadwaladr, the white greyhound of Richmond (a badge of John of Gaunt), the crown in the hawthorn bush (it was said that Richard III’s crown was found in a hawthorn bush at Bosworth) and the red and white roses intertwining to show the union of the Houses of York and Lancaster – to state his mission. Ramirez also examined the rest of the book – see http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/Results.asp – which consisted of John Killingworth’s planetary data and prophecies. Henry VII saw himself as a patron of science and scholarship and in Tudor times astrology was held in high esteem, it was seen as a science. This is also shown at Merton College where Bishop Richard Fitzwilliam’s sculptures on the ceilings are of astrological symbols next to the royal arms of Henry VII, showing that Henry was ruling not just England but the cosmos. Astrology was the science of the day and was seen as important. In 1502, William Parron, the Italian astrologer, presented Henry VII with an astrological manuscript – see http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/Results.aspwhich was a personal prediction for his family, unfortunately his predictions were not at all accurate, e.g. the future Henry VIII was going to be a loyal Catholic and father many sons, Elizabeth of York was going to live into her 80s… oh dear!

Henry VII, like Edward IV, had a library and although we don’t know where it was (probably at Richmond), Ramirez said that we know about it because it is recorded that he showed it to Catherine of Aragon to cheer her up when she was homesick. Previously, only religious and educational institutions had had libraries, where books were kept in chests, now monarchs were keeping books and displaying them.

The next book Ramirez looked at was a guide to the Holy land which still had its original Tudor binding, its sumptuous velvet cover. This tiny book showed just how beautiful and impressive illuminated manuscripts were even before you opened them. She then visited the Brockmans, a father and son team who use original techniques to repair and preserve historic books. They sew the pages by hand, then knock them into shape and press them, use gold leaf to gild the edges of the pages, make the covers from oak board and then cover them with velvet just like in Tudor times. It showed just how labour intensive the production of manuscripts was – 100s of hours just to put the book together after the scribes had completed the writing and illustrations.

Ramirez then looked at the most amazing book, the Quadripartite Indenture for Henry VII’s Chapel, which was a legal contract between the King and Westminster Abbey regarding Henry’s plans for his tomb, burial and afterlife – see http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/record.asp?MSID=7602&CollID=8&NStart=1498 and http://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2011/09/quadripartite-indenture.html. It was a huge book covered in burgundy velvet and emblazoned with Henry’s coat of arms and livery. It had silver gilded clasps decorated with roses and angels and then inside was pink damask and silver tins containing wax seals with images of the King in all his regalia. The book was an indenture, meaning that it was a legal contract in two parts: Henry would have had one and Westminster Abbey would have had the other half. It was an incredible book, not only in its appearance but also in the details Henry gave regarding his tomb, chapel and the rituals he wanted carried out. He had a chapel built at Westminster Abbey for his tomb, which is magnificent, and this still survives today even though the Abbey lost its monks when Henry’s son, Henry VIII, broke with Rome. It is an incredible chapel, with its 95 statues of saints, and it shows how deeply Catholic England was at this time and how Catholic Henry VII was – Ramirez pointed out that Henry VII was devoted to the doctrine of the immaculate conception.

Ramirez then moved on to Henry VIII who, as we know, became King in 1509. She explained how the image of the monarchy in his reign was “complex and magnificent”. The first manuscript she looked at was a gift from Antwerp merchants given to Henry in 1516 – see http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/record.asp?MSID=7527. This incredible manuscript was the perfect gift for the Renaissance king who loved education, sports, music etc. An allegorical poem was illustrated with a garden featuring a Tudor rose bush, daisies for Margaret of Scotland, marigolds for Mary Tudor, Queen of France, and a pomegranate tree laden with pomegranates for Catherine of Aragon, to show her fertility and the hope of heirs. This walled garden, protected by a lion, red dragon and white greyhound, was actually an island and so symbolised England. It was also protected by warships. Ramirez pointed out that the shape of the rose bush was actually that of a lyre and that the manuscript was also full of music written to delight the music loving king. The music was written in a circular form going around a rose – beautiful! The Brabant Ensemble then performed some of the music from the manuscript which had been written in praise of the Virgin Mary as a vessel, glorifying childbirth. This manuscript was clearly showing the expectations on Catherine of Aragon at this time.

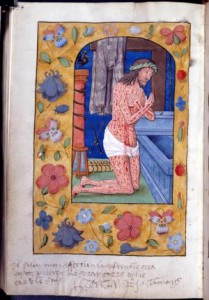

The next manuscript was the Book of Hours in which Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn inscribed messages to each other. On a page depicting an image of “the man of sorrows”, Henry wrote to Anne in French “If you remember my love in your prayers as strongly as I adore you, I shall hardly be forgotten, for I am yours. Henry R. forever” and Anne replied in English on a page depicting the Annunciation (the angel telling Mary that she was carrying God’s son) “By daily proof you shall me find To be to you both loving and kind”. What an insight into their relationship! Ramirez then explained that Henry’s determination to marry Anne Boleyn led to the break with Rome and actually the abolition of illuminated manuscripts of the ‘old religion’. Many thousands of books must have been lost and she then showed the surviving page of a choir book commissioned by Margaret of York, that’s all that is left of what must have been a beautiful book.

The next manuscript was the Book of Hours in which Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn inscribed messages to each other. On a page depicting an image of “the man of sorrows”, Henry wrote to Anne in French “If you remember my love in your prayers as strongly as I adore you, I shall hardly be forgotten, for I am yours. Henry R. forever” and Anne replied in English on a page depicting the Annunciation (the angel telling Mary that she was carrying God’s son) “By daily proof you shall me find To be to you both loving and kind”. What an insight into their relationship! Ramirez then explained that Henry’s determination to marry Anne Boleyn led to the break with Rome and actually the abolition of illuminated manuscripts of the ‘old religion’. Many thousands of books must have been lost and she then showed the surviving page of a choir book commissioned by Margaret of York, that’s all that is left of what must have been a beautiful book.

The final book Ramirez examined was Henry VIII’s psalter, his book of Psalms – see http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/record.asp?MSID=8719&CollID=16&NStart=20116. As Ramirez has pointed out in the previous episodes, King David was seen as a model of kingship so his Book of Psalms was read by kings, but in this psalter instead of images of David it has images of Henry as David! Henry, as head of the Church, is seeing himself as this important Biblical king. Ramirez also pointed out that the text is a literal reading of the Bible linking it to England at that time, David’s problems become Henry’s problems. The margins have a running commentary from Henry and his notes show that he was convinced that he was doing God’s will. Ramirez found a note of frailty amongst Henry’s margin notes – next to Psalm 36, a psalm on mortality, Henry had written “a sad saying”. It was obviously a book that Henry used and meditated on, it was a personal book and is very different to the old illuminated manuscripts which were public books on altars. Ramirez also commented on the difference between this book where a King is in control and odesn’t depend on the Church or the country, and the books of the Anglo-Saxon kings who saws their power coming from the Church.

By the end of the 16th century, the manuscript had finally been displaced by the printed book, even for royalty, but it was replaced by another symbol of power: the portrait. Ramirez explained that now monarchs were the head of the Church, they had to be more visible and portraits, with authorised copies made, could disseminate the image of the monarch throughout the land. While printed books could spread a message, portraits could spread the image and work as propaganda. She then spoke of how the likes of Hans Holbein and Nicholas Hilliard had a background in illuminated manuscripts but moved to portraits and miniatures. The iconography of portraits was first developed in the pages of illuminated manuscripts.

Ramirez concluded the programme, and the series, by talking about the historic weight and meaning of illuminated manuscripts. They were bespoke, not mass produced, and give us a unique insight into the private lives of kings and a very intimate experience.

If you’re in the UK, you can catch up with this episode of Illuminations: The Private Lives of Kings with BBC iPlayer, see http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b01b4v8t/Illuminations_The_Private_Lives_of_Medieval_Kings_Libraries_Gave_Us_Power/. If you’re in London between now and the 13th March make sure you go to the British Library’s special exhibition Royal Manuscripts: The Genius of Illumination – see Royal Manuscripts: The Genius of Illumination for more information and lots of beautiful images. There is also a book available at that link.

Many of the illuminated manuscripts can be seen on the British Library website by browsing their Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts – see http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/welcome.htm