Around 4th May 1536, in his daily report to Thomas Cromwell, Sir William Kingston, Constable of the Tower of London, wrote of Jane Boleyn, Lady Rochford, sending a message to her husband, George, who was imprisoned in the Tower.

Kingston’s letters to Cromwell were damaged in a fire in 1731 at Ashburnam House, but they are still an excellent primary source. Here is what he said about Jane’s message and George’s reaction (the dots are the illegible parts):

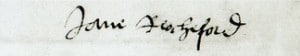

“After your departynge yesterday, Greneway gentelman ysshar cam to me & . . . Mr. Caro and Master Bryan commanded hym in the kyngs name to my [Lord of] Rotchfort from my lady hys wyf, and the message was now more . . . se how he dyd; and also she wold humly sut unto the kyngs hy[nes] . . . for hyr husband; and so he gaf hyr thanks […]”1

So, from this, we know that Sir Nicholas Carew and Sir Francis Bryan had commanded a gentleman usher called Greenway to carry a message from Jane Boleyn to George. The message was to see how he was doing in the Tower and to assure him that Jane would petition the king on his behalf. George sent a message of thanks back to her.

There is no evidence that Jane did petition Henry VIII or Thomas Cromwell, but that’s not to say that she didn’t. Although some historians have said that while she was sending this message to George she was actually busy giving Cromwell information and went on to become “the principal witness in the Crown’s case” against the Boleyns, this just is not backed up by contemporary sources.2 Justice John Spelman, in his report of the case against Anne Boleyn in 1536, named Bridget Wiltshire, Lady Wingfield, as posthumously providing evidence:

“And all the evidence was of bawdery and lechery, so that there was no such wh*re in the realm. Note that this matter was disclosed by a woman called Lady Wingfeilde, who had been a servant to the said queen and of the same qualities; and suddenly the said Wingfeilde became sick and a short time before her death showed this matter to one of her… [the rest is missing].”3

Lancelot de Carles, secretary to the French ambassador, recorded that it was an argument between Elizabeth Browne, Countess of Worcester, and her brother, Sir Anthony Browne, which brought the Boleyns down. In the argument about her own offence (possible adultery), Elizabeth allegedly defended herself by claiming that that her offence was nothing in comparison to the offences of the Queen, who had allowed members of the court to come into her chamber at all hours. Elizabeth went on to say that if her brother did not believe her, then he could find out more from Mark Smeaton. She then accused George Boleyn of having carnal knowledge of his sister, the Queen.4

John Husee, in his letters to Honor, Lady Lisle, wrote that three women had accused Anne Boleyn of infidelity: “The first accuser, the lady Worcester, and Nan Cobham with one maid mo; but the lady Worcester was the first ground”.5 It is not known who “Nan Cobham”6 was and we, of course, do not know who the “one maid more” was. Eric Ives believed the mystery maid to be Margery Horsman, a member of Anne’s household. In a letter to Sir William Fitzwilliam, treasurer of the household, Sir Edward Baynton, Anne Boleyn’s vice-chamberlain, had written about a problem with the case against Anne Boleyn, i.e. that only one man had confessed to sleeping with the queen, and at the same time mention his friendship with “mastres Margery” who had a “great fryndeship” with the Queen. It sounds like Baynton was trying to get information from Margery.7

Eustace Chapuys, imperial ambassador, makes no mention of Jane being the Crown’s star witness or being the one to provide the Crown with the evidence needed to bring down the Boleyns. It seems strange that Chapuys and Hussey would not have named her if she had, after all, it would have been quite a scandal if a woman had accused her husband of committing incest with the Queen. While Jane appears to have told the Crown of the Queen confiding in her about Henry VIII’s sexual problem, there is no evidence that she said any more than that or that she was a witness at the Boleyns’ trials.

You can read more about Jane Boleyn and the fall of Anne Boleyn in the following articles:

The 4th May 1536 was also the day on which Sir Francis Bryan and William Brereton were arrested – click here to read more.

Notes and Sources

- Cavendish, George (1825) The Life of Cardinal Wolsey, Volume 2, Samuel Weller Singer, p.220.

- Weir, Alison (2011) The Lady In The Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn, Ballantine Books, p. 212.

- ed. Baker, J.H. (1977) The Reports of Sir John Spelman, Selden Society, London, p. 70-71.

- de Carles, Lancelot, “Poème sur la Mort d’Anne Boleyn”, lines 861-864, in La Grande Bretagne devant L’Opinion Française depuis la Guerre de Cent Ans jusqu’a la Fin du XVI Siècle, George Ascoli, translated by Susan Walters Schmid in “Anne Boleyn, Lancelot de Carle, and the Uses of Documentary evidence”, dissertation, Arizona State University, 2009.

- ed. St Clare Byrne, Muriel (1981) The Lisle Letters, Volume 3, The University of Chicago Press, p. 377, letter 703a, John Husee to Lady Lisle, 24 May 1536.

- See Anne Boleyn’s Ladies-in-waiting for the various theories regarding Nan Cobham’s identity.

- Cavendish, p.226.