Today we have a guest post from my good friend, and author and history blogger, Gareth Russell. Thank you, Gareth.

Today we have a guest post from my good friend, and author and history blogger, Gareth Russell. Thank you, Gareth.

“… And we’ll live,

And pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh

At gilded butterflies, and hear poor rogues

Talk of court news; and we’ll talk with them too,

Who loses, and who wins; who’s in, who’s out;

And take upon ‘s the mystery of things,

As if we were God’s spies.”

William Shakespeare, King Lear

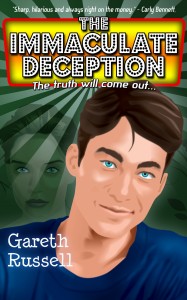

Both of my degrees were in history and because of that, and the blog I run, Confessions of a Ci-Devant, I think that a lot of people around me expected my first novel to be historical. The fact that I chose to write about a group of modern-day Belfast teenagers certainly raised more than a few eyebrows. On the surface, there didn’t seem to be anything in Popular, or in its sequel The Immaculate Deception, which had anything to do with history, royalty or the politics of court life. Yet, both books were profoundly influenced by my historical background, despite their contemporary setting. When one former professor of mine read it, he wrote to me: “There’s something profoundly medieval that permeates the whole atmosphere of the novel. Perhaps I’m being wistful?” He wasn’t. He was absolutely right. And I have to admit to a huge surge of relief when he noticed it! Popular may be set on Belfast’s Malone Road in the twenty-first century, but a lot of what happens is inspired by years of studying the internecine viciousness of royal courts and the people who led them. I’d like to share with you how that process happened.

For a start, some of the characters are loosely inspired by historical personalities. The series turns on the machinations of an ethereally beautiful young woman called Meredith Harper, who is mature and knowing in a way that might better fit a chatelaine of long ago than a girl of 2013. Described in the novel’s opening chapter as “rich, popular, clever, elegant, manipulative, graceful and almost unnaturally beautiful,”1 Meredith was deliberately written as someone who had ditched the doe-eyed insecurities and neuroticism that seem to permeate so many modern portrayals of teenage girls. Instead, like the power players of the Renaissance and Baroque, Meredith Harper is slick, glamorous, intelligent and utterly ruthless. What’s more, she knows it. There’s no false modesty and honey-wrapped words of faux comfort with Meredith. This is no “poor little rich girl.” Quite the opposite. This is a girl who is acutely aware of her capabilities and who revels in the social power that her beauty and her family’s wealth have given her. Rather than feel guilty about the privilege she’s had the good luck to be born into, Meredith has an ancien régime girl’s determination to use it to her full advantage. She has Anne Boleyn’s confidence and Anne Boleyn’s brains, but the devastating good-looks and social ambition of Gabrielle de Polignac. She does not suffer fools lightly and she is determined to stay at the top of the social pyramid, come what may. Meredith enjoys the social hierarchy and feels no need to question it; indeed, like a courtier at Versailles, she actively despises those who do. As appalling as that may seem, that is how many of the women of the past felt and acted. I think we have seen enough of the weak-willed and boy-crazy teen queen bee; instead, I wanted to create a character who happened to be alive in the twenty-first century, but who would arguably have flourished far more had she been born in the eighteenth. The seed of the character was planted during rehearsals for a play I had written about the collapse of the French monarchy, in which my friend Ellen casually wondered what Gabrielle would have been like if she had lived today. Meredith is no more a carbon copy of Gabrielle de Polignac than she is of Anne Boleyn, but she shares many of their attributes. Rather than dismissing her as a bitchy self-obsessive, I was interested in portraying her strength and her indifference to the criteria set for her by men and women who resent her.

A modern high school also endures many of the conditions that helped make historical courts such tribal or factional places. A relatively large group of people are forced to co-exist alongside one another in a closed environment for a prolonged period of time. Inevitably, cliques form, agendas are set, personalities clash and many are sucked into playing a game that operates under a series of standards and goals that seem bizarre to outsiders. Courts were places in which the politics of the visual – how you looked and how you acted – were hugely important. Where one sat and with who was a make-or-break decision. One’s social credibility was often determined by a thousand petty or trivial attitudes, all of which seemed far more important because one was trapped living with hundreds of people who all subscribed to the same warped values system. Does this all sound utterly exhausting? Yes, absolutely. Does it make for a phenomenal setting, where an author can give free rein to characters bouncing off each other in an hermetically-sealed world in which nothing on the outside really seems to matter? Of course it does. In Popular, friends are livid to discover that someone is upstaging them by going as Marie-Antoinette to a sixteenth birthday party. In its sequels, friendships nearly end over who’s trying out for the school rugby team and who’s running against who in the social committee elections. In 1575, the Earl of Oxford apparently broke wind in front of Queen Elizabeth I and was so mortified by what he had done that he fled the country for seven years. Louis XIV’s mistress, Louise de la Vallière, was so determined to show her face at a palace ball that she rolled out of bed and into her ball-gown only hours after giving birth to the King’s bastard child. Nell Gwyn, fearing that she was about to be replaced by Moll Flanders, spiked her rival’s chocolate with laxative, hours before she was due to meet the King. Some see it is a telling indicator of how much Anne Boleyn’s power was slipping in 1536 when her brother was passed-over for the honour of being inducted into the Knights of the Garter; instead, the King chose to favour Sir Nicholas Carew, a friend of the Seymour family. In 1699, the general who helped win the Battle of the Boyne, Lord Portland, openly wept in front of King William of Orange and resigned all his courtly offices because the King seemed to prefer the company of the handsome young Arnold van Keppel, whom he had made Earl of Albemarle. These kinds of stories litter aristocratic history and they go to show that while the settings between a palace and a school may seem very different, the sociology is often frighteningly similar. As a writer, and as an historian, I find that fascinating.

This creates a problem, however, in trying to get your readers to take these things seriously. If they don’t take your characters seriously, then they’re going to dismiss the whole story as froth and nonsense – something that’s not worthy of their time. If I’m honest, that has been a slight frustration with Popular. In all due modesty, I don’t think the books are like that. There’s a fantastic quote from Sofia Coppola, when she was directing a biopic of Marie-Antoinette starring Kirsten Dunst back in 2006. She remarked that it was annoying that people seemed to think that just because people were interested in something frivolous, it meant that they couldn’t also have depth. That’s an idea I firmly agree with. Many of The Anne Boleyn Files’ regular readers will know that much of what Anne Boleyn or the Henrician court fixated on might seem unutterably trivial to a modern reader – what they wore, who handed them what at dinner, who got what title, who stood closest to the members of the royal families and who wore what colours in a joust. Yet, in their world, these things mattered. I have tried, as best I can, to write a world in Popular and The Immaculate Deception (and its forthcoming sequel, The Age of Vengeance) in which I am not judging my characters for their preoccupations, but rather trying to take those preoccupations as seriously as they do. And, yes, have a little fun along the way. Like the Duc de Saint-Simon, I have some of my characters (for instance, Cameron) look at the whole system with a gently satirical eye. But when the chips are down, Cameron, like Saint-Simon, will go along with the system wholeheartedly. I have several characters – Imogen, Meredith, Kerry or Anastasia – who care very much about what they wear and how they look. As far as the arbiters of modern depth go, they shouldn’t. We’re taught relentlessly that it’s what’s inside that counts and if you don’t subscribe to that, you’re apparently only a parody of worthy human being. But part of me had an absolute riot of a time giving these girls sensibilities that belonged to a rarefied world in which how they dressed was part of the image they cultivated; their fashion is an integral part of their social personas and the effect they have on those around them. Caroline Weber and Aileen Ribeiro’s books on how fashion was used by both royalists and republicans during the French Revolution were as much a help as the modern-day issues of Vogue and GQ, which I bought religiously during the writing process.2 I hope I’ve been able to give my girls a sense of steely determination with their fashion. To quote the late, great Eric Ives in his biography of Anne Boleyn: “Her preoccupation with glamour, which older historians despised as feminine weakness, has now been recognized as a concern with ‘image’, ‘presentation’ and ‘message’ which was as integral to the exercise of power in the sixteenth century as it is in the modern world.”3 I try, always, to take my characters seriously, because it is the easiest thing in the world to mock someone who is interested in what they wear and how they look.

High schools, like courts, also breed a less glamorous aspect of life – namely tribal loyalties juxtaposed with shifting sands of friendship. Any good movie or book about life in a palace will capture something of the frightening vitality of faction or, in high-school-speak, cliques. One of the reasons why George R.R. Martins’ A Song of Ice and Fire (dramatized as Game of Thrones by HBO) works so brilliantly as fiction is because he captures the nit and grit of palace in-fighting and feudal politics at their very worst. (Or best, depending on how grateful you are for the drama.) By the end of book two, The Immaculate Deception, the eponymous popular clique are shaping up for the mother of all battles with their in-school rivals, led by the hug-dispensing Coral Andrews – who is every bit as ruthless, but far more hypocritical, as her chic and vicious enemy, Meredith Harper. The full damage of the gossip network, which has felled and ruined as many reputations in high schools as it did in palaces, is also shown in the books. Blake and Cameron both struggle, with mixed results, against the rising tide of innuendo and hearsay, while Imogen and Meredith show themselves cunningly adept at manipulating the rumour mill to fulfil their own agenda. Poor Mark Kingston, who has the same kind of love-hate relationship with the popularity hierarchy as the troubled poet Thomas Wyatt had towards Henry VIII’s court, naively crashes into some very uncomfortable and hurtful situations, because he fails to realise how badly he has misjudged the situation around him.4 Charm and spite, loyalty and betrayal, are enduring conditions of the human experience, but they are often on their fullest and most dramatic display when magnified by a closed and insular society.

Popular and The Immaculate Deception are not historical novels. Much of their humour, like their syntax, derives purely and squarely from the modern day and things I have witnessed and experienced. However, I have always firmly believed that history is ultimately the story of people and studying history has therefore not just increased my knowledge of the past, but also of the present. In short, it has increased my understanding of, and my interest in, people. The how and the where of Popular may be very different to the world of Anne Boleyn and the Tudors, but the what and the why are deliberately quite similar. I like to think that Popular’s characters could survive in a court; indeed, in their own way, they already are one. The beautiful faction leader-cum-society hostess in the shape of Meredith, her urbane and sophisticated ally Cameron, extravagant Imogen, Kerry, who wants only a life full of ease and prettiness, misguidedly noble Mark, the love-tortured troubadour Blake and a host of other people whose looks, families, athletic prowess, wit and connections help turn them into miniature celebrities inside their own very goldfish bowl. Looked at from that perspective, I don’t think that’s such a stretch from one to the other. Of course, it’s exaggerated and no one is going to be marched to the scaffold at the end of the Popular series, but the refinements of cruelty and glamour are eternal. Love, loss, friendship and factionalism don’t ever really go away. Part tragedy and part a comedy of manners, Popular was supposed to be written in a way that reflected what I’ve always enjoyed most about studying the hierarchies of the past – at times you despair for them, at times you laugh at them and at times you cheer them on, even though you suspect that you shouldn’t. I could not have written these books without the knowledge that came from history, nor the encouragement history lovers, on this forum and others, have given me. These books have been a joy to create and I hope that anyone with a similar love of history who read them would be able to enjoy them, too.

About Gareth Russell

Gareth Russell is twenty-six years-old and originally from Belfast, Northern Ireland. He studied History at the University of Oxford and completed his postgraduate in medieval history at Queen’s University, Belfast, where he produced a dissertation detailing the intricacies and importance of court life under Catherine Howard. In 2012, he spoke on two of the History Tours of Britain’s special tours – The Executed Queens Tour, where he spoke on Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard, and The Anne Boleyn Experience, where he spoke on the Queens’ households under all six of Henry VIII’s wives – how each queen’s personality influenced court life and how the organisation of the household managed to stay the same.

His first novel Popular was published in the UK and Ireland by Penguin in 2011. In 2012, it was updated and re-issued with a new cover by MadeGlobal, along with its first sequel, The Immaculate Deception. Gareth runs the blog Confessions of a Ci-Devant and a website for the Popular series (www.thepopularseries.com.) He is currently working on the third instalment in the Popular series and his first piece of non-fiction. Book 1 in the series, Popular, has already been adapted twice for the stage and extracts from the second, with Joe Williams, David Paulin, Lauren Browne and Claire Handley, were performed on the Belfast stage in 2013.

Notes and Sources

- Gareth Russell, Popular (London, 2011), p. 1

- Caroline Weber, Queen of Fashion: What Marie-Antoinette wore to the Revolution (New York, 2006); Aileen Ribeiro, Fashion in the French Revolution (London, 1988)

- E.W. Ives, The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn (Oxford, 2004), p. xiii.

- Wyatt’s poetry reflects a revulsion with the morality and in-fighting of Henry VIII’s court, yet his career showed a total inability to stay away from it. An addiction to life in the court forms a cornerstone of the theories put forward by the lovely Julia Fox in her book Jane Boleyn: The Infamous Lady Rochford (London, 2007). For a discussion of Wyatt’s attitudes to the hypocrisy, extravagance and indulgence of court life, see Ives, pp. 8-10.