Following on from my post a few weeks ago about Anne Boleyn’s 1534 mystery pregnancy, I wanted to examine the various theories regarding Anne’s final pregnancy which ended in January 1536, less than four months before her execution.

A Straightforward Miscarriage

The majority of historians and authors believe that Anne Boleyn’s final pregnancy ended with a miscarriage on 29th January 1536, the day of Catherine of Aragon’s burial and a few days after Henry VIII suffered a serious jousting accident.

There are three main pieces of contemporary evidence for the miscarriage, a letter written by Eustace Chapuys, the Imperial ambassador, and the chronicles of Charles Wriothesley and Edward Hall:

“On the day of the interment [Catherine of Aragon’s funeral] the Concubine had an abortion which seemed to be a male child which she had not borne 3½ months, at which the King has shown great distress. The said concubine wished to lay the blame on the duke of Norfolk, whom she hates, saying he frightened her by bringing the news of the fall the King had six days before. But it is well known that is not the cause, for it was told her in a way that she should not be alarmed or attach much importance to it. Some think it was owing to her own incapacity to bear children, others to a fear that the King would treat her like the late Queen, especially considering the treatment shown to a lady of the Court, named Mistress Semel, to whom, as many say, he has lately made great presents.”1 Eustace Chapuys to Charles V, 10th February 1536.

“And in February folowyng was quene Anne brought a bedde of a childe before her tyme, whiche was born dead.”2 Edward Hall

“This yeare also, three daies before Candlemas, Queene Anne was brought a bedd and delivered of a man chield, as it was said, afore her tyme, for she said that she had reckoned herself at that tyme but fiftene weekes gonne with chield…”3 Charles Wriothesley

All three sources state that Anne miscarried her baby, and two of them state that it was a boy and that it was at the three and a half month mark. Wriothesley goes on to put forward the idea that the miscarriage was caused by Anne suffering shock at the news of Henry VIII’s jousting accident, as does Chapuys. The dates differ, with Chapuys stating that it happened on 29th January, Hall saying February and Wriothesley saying the 30th January, and Raphael Holinshed saying in his chronicle the 29th, but we can assume that it happened at the end of January.

A Deformed Foetus

In the novel “The Other Boleyn Girl” by Philippa Gregory, Anne Boleyn miscarries “a baby horridly malformed, with a spine flayed open and a huge head, twice as large as the spindly little body”.4 Now, obviously this is just a novel but Gregory used the work of historian Retha Warnicke as a source and Warnicke believes that Anne did miscarry a deformed foetus. In “The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn”, and also her essay “Sexual Heresy at the Court of Henry VIII”, Warnicke puts forward the idea that Anne’s miscarriage was a factor in her fall because it was “no ordinary miscarriage”5 and that it was “an unforgivable act”6. According to Warnicke, the foetus was deformed and this was seen as an evil omen and a sign that Anne had committed illicit sexual acts or been involved in witchcraft. Warnicke believes this because:

- Anne was charged with committing incest with her brother, George, who Warnicke believes was Mark Smeaton’s lover.

- Anne was charged with adultery with Smeaton, Norris, Brereton and Weston, who Warnicke believes to have been “suspected of having violated the Buggery Statute” and who “were known for their licentious behaviour”7

- There seems to have been a delay between the miscarriage and the news being announced, showing that there was something odd about it – Chapuys did not report it until 10th February 1536.

- “From late January the councillors moved to protect Henry’s honour by leaking erroneous information about his consort before the public announcement of her miscarriage”8 so that the sin would be seen as Anne’s and not the King’s.

However, in my own reading on pregnancy and childbirth in Tudor times,9 I have learned that deformities, or things like birthmarks, were actually thought to have been caused by things the mother had seen during pregnancy, rather than the parents necessarily committing a sexual sin. Seeing a hare, for example, was thought to result in a baby being born with a harelip, eating strawberries was thought to result in a strawberry birthmark, and deformities were thought to be caused by shocks or sudden frights, by seeing ugly sights or pictures, or by having contact with animals. These were superstitious times.

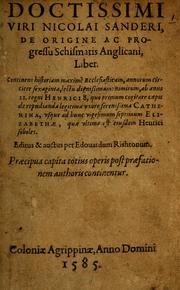

The only source, anyway, for Anne miscarrying a deformed foetus is Nicholas Sander, a Catholic recusant writing in the reign of Anne’s daughter, Elizabeth I. His book “De origine ac progressu schismatis Anglicani” was published in 1585 and translated from Latin into English by David Lewis in 1877 as “Rise and Growth of the Anglican Schism”. In the English translation, Sander wrote of Anne’s miscarriage:

“The time had now come when Anne was to be again a mother, but she brought forth only a shapeless mass

of flesh.”10

Sander went on to write of how Anne blamed Henry VIII for the miscarriage, crying “See, how well I must be since the day I caught that abandoned woman Jane sitting on your knees”, but he did not attempt to explain the “shapeless mass” or give any more details. I’m sure that if he thought it was important and suggestive of sin or witchcraft that he would have mentioned it. Sander is the only source that describes Anne’s baby in this way, and he was writing much later (he wasn’t born until c.1530). As Professor Eric Ives pointed out “no deformed foetus was mentioned at the time or later in Henry’s reign, despite Anne’s disgrace”, nor was it mentioned in Mary I’s reign “when there was every motive and opportunity to blacken Anne”.11 Ives concluded that “it is as little worthy of credence as his assertion that Henry VIII was Anne’s father” and I agree wholeheartedly. Sander, as a Catholic exile, had every reason to blacken the name of Elizabeth I and her mother.

There is also no evidence that the five men executed in May 1536 were involved in “illicit” sexual acts, or that Anne was involved in witchcraft.

Phantom Pregnancy

In her recent book on Anne Boleyn, Sylwia Zupanec12 discusses Anne’s 1536 miscarriage and puts forward the idea that it may have been a phantom/false pregnancy and not a miscarriage at all. The evidence she puts forward for this is:

- That Sander actually did not mention a “shapeless mass of flesh” but, according to Zupanec, “In Latin described the outcome of Anne’s pregnancy as ‘mola'”. She goes on to say that “Sander’s account is not précising the information about what had happened on 29 January 1536 so he could have meant that Anne Boleyn had suffered from phantom pregnancy, miscarried an undeveloped foetus or expelled some kind of tumour.”13 Zupanec believes that Sander’s work was “incorrectly translated” and that as a result of this historians have misinterpreted it.14 She cites two Latin works to back up her translation of “mola” as a false conception, “M. Verrii Flacci Quae Extant: Et Sexti Pompeii Festi De Verborum Significatione”15 and “Lexicon Philosophicum Terminorum Philosophis Usitatorum”16 by Johannes Micraelius, Latin glossaries of terms.

- That rumours spread around Europe saying that Anne had pretended to miscarry and that she hadn’t been pregnant at all. Zupanec quotes the Bishop of Faenza writing to Prothonotary Ambrogio on 10th March 1536, saying that Francis I had said “that “that woman” pretended to have miscarried of a son, not being really with child, and, to keep up the deceit, would allow no one to attend on her but her sister, whom the French king knew here in France “per una grandissima ribalda et infame sopre tutte.””17 She also quotes Dr Ortiz writing to the Empress on 22nd March 1536: “La Ana feared that the King would leave her, and it was thought that the reason of her pretending the miscarriage of a son was that the King might not leave her, seeing that she conceived sons.”18 Zupanec believes Sander’s words and these reports, when combined, suggest that Anne may have been “simply suffering from illness unknown to her contemporaries”,19 i.e. a phantom or false pregnancy.

However, if you read Sander’s original Latin, as I have done, Sander does not use the word “mola”. Here is what Sander says about Anne’s miscarriage in his book “De origine ac progressu schismatis Anglicani”:

“”Venerat tempus quo Anna iterum pareret, peperit autem informem quandum carnis molem, ac praeterea nihil.”20

So, he says “molem” and not “mola” and the two words have completely different meanings.

My Latin is not very good at all, so I asked Phillipa Madams (thank you, Phillipa!), a Latin expert and Latin teacher, to translate the sentence by Nicholas Sander and also the Latin references given by Zupanec. Phillipa translated Sander’s words as “an unformed shapeless mass of flesh”, which was in keeping with Lewis’s 19th century translation. As far as the references cited by Zupanec to back up the idea that “mola” meant a “false conception”, Phillipa stated that the first one (by Marcus Verrius Flaccus and Sextus Pompeius Festus the famous Roman grammarians) gave a definition of the word “mola” as “a millstone”, used for milling grain, and there was nothing about conception or pregnancy in the definition.

The second one (Johannes Micraelius’ glossary of Latin terms) was a definition for “mola carnis” (not “carnis molem”), saying that it was a “useless conception”. Indeed, as one of Phillipa’s students, Ellen, found, there is a condition called a molar pregnancy which is caused by problems with fertilization. Perhaps this is what Zupanec is referring to when she says “false conception”, rather than a phantom pregnancy, but this is a very rare condition and today is more common in teenage pregnancies or in women over 45. In a molar pregnancy, the cells of the placenta behave abnormally and “grow as fluid-filled sacs (cysts) with the appearance of white grapes”.21 In a complete molar pregnancy, a mass of abnormal cells grow and no foetus develops, and in the case of a partial molar pregnancy some normal placental tissue forms along with an abnormal foetus which dies in early pregnancy. In most cases, today, there are no signs that the pregnancy is anything but normal, until the woman has a scan, but in some cases the woman can experience bleeding or can lose the developing foetus. The treatment is for the woman to have the “mole” removed by surgery (a dilatation and curettage, or D&C), because if it is left then there can be complications, such as the growth becoming cancerous. The woman does not miscarry the “mole” or “tumour”. Sander is quite specific in saying that Anne “brought forth only a shapeless mass of flesh”, i.e. that she miscarried or gave birth to something. A foetus in the early stages of pregnancy may have appeared as a “shapeless mass of flesh” anyway to untrained eyes.

A phantom pregnancy, or false pregnancy (pseudocyesis), is when a woman experiences many of the symptoms of a real pregnancy and believes that she is pregnant, but there is no foetus, or placenta. This just doesn’t fit with what we know about Anne in January 1536 – Chapuys, Hall, Wriothesley and Sander all write of Anne miscarrying rather than being “pregnant” for months and then there being no baby born at the end of it. We can rule out a false pregnancy in this case.

As I said before, “mola” and “molem” are two completely different words and neither Phillipa nor I can understand why the references cited are definitions of a word not used by Sander in his book. Sander clearly wrote “informem quandum carnis molem” and “molem” simply means “mass”. Phillipa explained to me “Carnis is clearly and unambiguously referring to flesh and informem can have a range of meanings from shapeless to monstrous. Even without the misunderstanding of mola/molem she clearly gave birth to something.”22 The Latin translation by David Lewis is, therefore, correct and has not been misinterpreted by historians. There is no way, in my opinion, that Sander’s words can be read as suggesting that Anne was suffering from a phantom pregnancy and it doesn’t fit the symptoms or outcome of a molar pregnancy either. That’s even if we take Sander’s words seriously. We don’t know what he’s basing his story on and we don’t take his description of Anne seriously – the six fingers, projecting tooth etc. – so we need to take his description of the miscarriage with a hefty pinch of salt too.

As far as the rumours of Anne pretending to be pregnant are concerned, they are likely to have been just that: rumours. We have Chapuys, Wriothesley and Hall, and later Holinshed23 and Sander, all writing of a miscarriage. Professor Eric Ives pointed out in his biography of Anne Boleyn that Wriothesley was Windsor Herald, a man whose “post gave him a ready entrée to the court” and that “his cousin Thomas was clerk of the signet and close to Cromwell”,24 so he would have been well informed. There is no reason to doubt these reports.

Conclusion

Having looked at the various theories and having examined the contemporary sources, I believe that Anne suffered an ordinary, but tragic, miscarriage in January 1536. That is what the evidence points to and that is what I will believe. It was obviously a huge blow to the royal couple, and may have been a factor in her downfall, but there was nothing strange about this miscarriage.

What do you think?

Update

Thank you so much to Louise Stephens for drawing my attention to the fact that Lancelot de Carles also writes of Anne miscarrying a male baby. I have Lancelot de Carles’ “Poème sur la Mort d’Anne Boleyn” so I was able to find the lines:

“Adoncq le Roy, s’en allant a la chasse,

Cheut de cheval rudement en la place,

Dont bien cuydoit que pur ceste adventure

Il dust payer le tribut de nature:

Quant la Royne eut la nouvelle entendue,

Peu s’en faillut qu’el ne chuet estendue

Morte d’ennuy, tant que fort offensa

Son ventre plain et son fruict advança,

Et enfanta ung beau filz avant terme,

Qui nasquit mort dont versa mainte lerme.”25

Here, de Carles is saying that the news of Henry VIII’s jousting accident caused Anne to collapse, landing on her stomach, and this caused her to give birth “avant terme”, prematurely, to “ung beau filz”, a beautiful son, who was born dead. He backs up what Wriothesley, Hall, Chapuys and Holinshed say and de Carles was the secretary of the French ambassador so is likely to have received information from Cromwell.

Notes and Sources

- LP x.282

- Hall’s Chronicle, p818

- A chronicle of England during the reigns of the Tudors, from A.D. 1485 to 1559, Charles Wriothesley, p 33

- The Other Boleyn Girl, Philippa Gregory, Touchstone 2001, p589

- The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn, Retha Warnicke, p191

- Sexual Heresy at the Court of Henry VIII, The Historical Journal Volume 30, Issue 02, June 1987, p260

- The Rise and Fall,p214

- Sexual Heresy, p258

- Birth, Marriage, and Death: Ritual, Religion, and the Life Cycle in Tudor and Stuart England, David Cressy, and Women and Gender in Early Modern Europe, Merry E. Wiesner.

- Rise and Growth of the Anglican Schism, Nicholas Sander, Burns and Oates, 1887, p132

- The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn, Eric Ives, p297

- The daring truth about Anne Boleyn: cutting through the myth, Sylwia Zupanec, 2012, Kindle version, Chapter 9

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- M. Verrii Flacci Quae Extant: Et Sexti Pompeii Festi De Verborum Significatione, libri XX, 1826, p424

- Lexicon Philosophicum Terminorum Philosophis Usitatorum, Johannes Micraelius, 1661, p825

- LP x.450

- LP x.528

- Zupanec

- De origine ac progressu schismatis Anglicani, Nicholas Sander, 1585, p166

- Molar Pregnancy, NHS. I also looked at Hydatidiform Mole and Choriocarcinoma UK Information and Support Service and Cancer Research UK

- Phillipa Madams, 2nd December 2012

- Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland, Raphael Holinshed, p796

- Eric Ives, p296

- Poème sur la Mort d’Anne Boleyn, Lancelot de Carles, lines 317-326, in La Grande Bretagne devant L’Opinion Française depuis la Guerre de Cent Ans jusqu’a la Fin du XVI Siècle, George Ascoli