This day in history, 31st May 1533, saw the lavish and triumphant coronation procession of Anne Boleyn from the Royal Palace of the Tower of London to Westminster Hall in readiness for her coronation on the 1st June 1533.

Anne and Henry had waited years for this moment so it is little wonder that the procession was one of splendour. As I have said before, it was not just a coronation procession, it was a statement that Anne Boleyn was Henry’s rightful wife and queen, and that she was carrying the heir to the English throne.

Nasim Tadghighi wrote a wonderful article last year about this procession after she walked the route, so I am reposting it here for those of you who have not read it. Thanks so much, Nasim!

Anne Boleyn’s Coronation Procession

by Nasim Tadghighi

On 1st June 1533, Anne Boleyn was crowned Queen of England in Westminster Abbey. The ceremony marked the zenith of the coronation proceedings, though several days beforehand she had been celebrated as the new queen in a series of spectacular events. The most impressive was a procession that took place on Saturday 31st May. The pageant took Anne from the Tower to Westminster Hall, the site of her coronation feast planned for the following day. The procession wound its way through the most important and busy streets of the city, each area being associated with different trades and schools. Along the way Anne was entertained with sumptuous displays that ranged in sophistication; from an endearing display of schoolchildren dressed up as merchants on Fenchurch Street to a feature designed by Holbein on the corner of affixing Gracechurch Street.

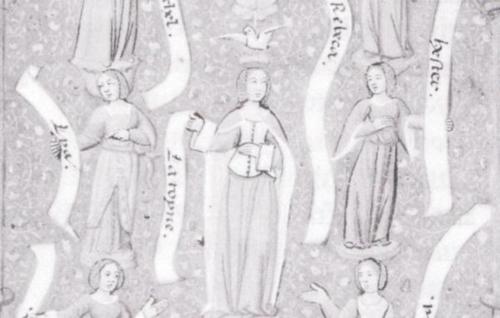

These spectacles and the landmarks cited in descriptions of the procession are long gone. What was not naturally demolished over the ages, fell victim to the Great Fire of 1666. Worse still, we lack images of Anne’s coronation procession except for a preliminary drawing by Holbein of the pageant he designed for Gracechurch Street (see picture).

So we could say that it is hard to deduce what the coronation procession was like and how Anne herself experienced the event. Yet though we lack the buildings she knew and images of the pageants designed for her on that day, we do possess contemporary and later accounts. These sources give us some idea of what the procession was like for Anne and also provide us with a general insight into Tudor London. Furthermore our understanding of the day can be enhanced by our ability to retrace Anne’s steps. This can be hard given that the city today is so different from what it was in 1533. The numerous business complexes and coffee shops are distracting, and can deter us from truly understanding the experiences of those who participating in and witnessed the event. But I think in order to understand what the day was like it is useful to take into account the route of the journey by walking it. Walking the route strengthens our perception of the events and conveys to us a further understanding that reading valuable documents alone cannot provide.

Planning the Coronation

According to Eric Ives and Gordon Kipling, the procession was planned in a very short space of time. Though they disagree with one another about the exact length of preparation (for Ives it was about four weeks, for Kipling it was barely two), they nonetheless see the procession as something that was quickly compiled.

Anne had been pronounced as queen on the 12th April 1533 in the Chapel Royal at Greenwich and naturally she and Henry wanted her legitimacy as queen consort to be further enforced by Anne being anointed as such, and publicly displayed as queen to the capital. So important was this that Henry went to the unbelievable length of having Anne crowned with St. Edward the Confessor’s crown, though no previous consort was ever granted the privilege of using the crown specifically deemed for ruling monarchs. By spring 1533 Anne was also pregnant, and the coronation needed to occur prior to the birth of the hoped for male heir. Anne’s pregnancy was mentioned again and again throughout the pageant, and she visibly showed off her state throughout. Coronations of queen consorts and queen regnants (as it is during the Tudor period that we see for the first time coronations of queen regnants), always propagated the subject of fertility, for the bearing of heirs was a queen’s main duty. For Anne, the day of her coronation procession was much about the celebration of her unborn child as it was about her. Alice Hunt has regarded Anne’s coronation as Henry VIII’s second coronation, but I think it is more appropriate to say that this marked the ‘couple’s coronation’ and certainly their moment of triumph more than any individualistic approach. Quite simply, Anne was witnessing a celebration of her union with Henry.

The Coronation Route

As mentioned previously, the procession started at the Tower. It was supposed to start at 2pm, but ended up being three hours late. A contemporary pamphlet helps us deduce what happened next. In The noble tryumphaunt coronacyon of quene Anne (1533), it states that the mayor of London ‘mette the queens grace at her coming forthe of the towre/and all his bretherne and aldermen standing in chepe’. He had with him ‘the craftes of the cyte’ to receive her. Did Anne possible reflect on the fact that her great-grandfather, who had been mayor of the same city, would have performed similar functions? Perhaps, though her connections to the city in that regard appear not to have been focused upon in the festivities.

The procession travelled to the north-west of the Tower, for it soon was at Fenchurch Street. It seems probable that Anne passed through Tower Hill, the famous execution site. Nearly three years later her supposed ‘lovers’, including her brother, were executed on this spot. The procession then arrived at Fenchurch Street, where Anne was greeted with her first pageant; ‘a pagent fayre & semly/ w’ certayne chylsdren which saluted her grace with great honour and prayse’. The children were dressed as English and French merchants, and gave speeches in these languages.

The procession moved down the street until it reached Gracechurch Street (or, as it was also called in its day ‘Gracious church’). On the corner, Anne witnessed one of the most magnificent of the six-full scale pageants planned for the day. This pageant, sponsored by the merchants of the Steelyard and described in the contemporary pamphlet as ‘costly’, was designed by Holbein. Apollo is surrounded by the Nine Muses, ‘amonge the mountains/syteyng on the mount of Pernasus/and every of them havynge their instruments & apparayle acordyng to the deicryption of poetes.’ The Nine Graces bestowed gifts upon Anne, whilst red wine flowed from the fountain the ensemble where positioned upon. Today a Marks and Spencers stands on the corner that leads Fenchurch Street to Gracechurch!

The procession continued down Gracechurch Street when it stopped at Leadenhall for another display. Leadenhall was a famous food market; in Anne’s day it was notable for the sale of fish, meat, poultry and corn. Here a castle was constructed, with a ‘heavenly rouse’ at the top whilst red and white roses sprung forth. From this heavenly rose descended a falcon which landed on a stump. An angel in armour then descended and crowned the falcon. Evidently this pageant recreated Anne’s badge. The spectacle at Leadenhall also drew attention to Anne’s namesake, St Anne, mother of the Virgin. St Anne and her children, the three Marys, and their own children, sat beneath the stump the falcon rested upon. Here Anne Boleyn was addressed directly by a verse composed by Nicholas Udall:

‘Honour and grace bee to our queene Anne.

ffor whose cause an Aungell Celestiall

Descendeth, the ffalcon as white as swanne

To croun with a Diademe Imperiall!

In hir honour reioyce wee all,

ffor it cummeth from God, and not of man.

Honour and grace bee to our Queene Anne!’

The message was clear – Anne and her child were England’s ‘hope’. The name Anne was equated with ‘grace’ promoting the idea that through Anne’s marriage to the monarch and the bearing of issue, the realm would receive God’s favour, as St Anne was favoured by being the mother of the Holy Virgin. So not too much pressure on Anne Boleyn there! (Ives amusingly points out that everyone was rather careful not to mention that St Anne had produced only daughters!)

This pageant was familiar to Anne in more than one way. Her badge had been reconstructed, but the pageant also replicated a traditional element in coronation processions of queen consorts. It was popular to show angels or other celestial creatures descending with crowns from heaven and bearing the crown to the queen or crowning an object meant to represent her. This feature was present in a coronation of a queen consort that Anne witnessed – the coronation of Queen Claude of France. Claude had been entertained with a mechanical dove, representing the Holy Ghost, offering her a crown. Fortunately we have an image of this scene, provided in Pierre Gringoire’s Pageant for the Paris Entry of Queen Claude (1512). Did Anne reminisce about her days in France when she saw this flattering display?

The coronation procession then moved down Cornhill Street, which is a left turn off Gracechurch. The street today is full of expensive designer boutiques; Anne would approve! Everywhere she looked there would have been magnificent trappings, for the street was covered in tapestries and carpets, with crimson and scarlet cloth. At the conduit on the street she was entertained by a pageant starring the Three Graces. Here wine flowed continuously from a fountain. Fortunately we have no record of the citizens benefiting a little too much from the free wine and restoring to the antics that are now a familiar sight every Friday/Saturday night in central London!

The procession moved past what is today the Royal Exchange and went straight on to Poultry and then onto Cheapside. Two pageants were held at Cheapside; the first at the Cheapside Cross (now long gone), and one at the Great Conduit which was situated near Honey Lane. The one at ‘the crosse in chepe’ involved the Recorder of London and the aldermen who greeted Anne and spoke verses to her. As contemporary chronicler Edward Hall noted, the Recorder, ‘gaue to her in the name of the Citie a thousand markes in golde, in a Purse of golde, whiche she thankefully accepted with many godly words’.

At the Great Conduit, the Judgment of Paris was recreated. Paris of Troy is asked to judge who of three goddess – Juno, Pallas and Venus – should be rewarded with the golden apple, a prize which he granted to Venus. The renowned story is given a slight twist here. When Anne approached the display Paris was just about to give the apple to Venus but upon seeing Anne he grants her the prize, for her exceeding beauty and grace:

Paris:

‘yet, to bee plain

Here is the fouerthe ladie now in our presence,

Moste worthie to haue it of due congruence,

As pereles in riches, wit, and beautee,

Whiche are but sundrie qualitees in you three.

But for hir worthynes, this aple of gold

Is to symple a reward a thousand fold.’

Instead of the procession travelling in a straight direction, which would have taken Anne through south of Smithfield (the famous place of execution), it turned south-west, to pass by St Paul’s Cathedral. Upon arriving at the gates, another pageant was held. Three ladies, dressed magnificently, were seated on the floor. They appear to have had something affixed to their heads that together contained the message: ‘Regina Anna! Prospere, procede, et regna!’ They all held tablets containing biblical passages, and yet again they included angels holding out crowns to Anne. They then spoke a prophecy that Anne would one day have a son and through that child ‘there shall be a golden world unto the people’. Anne was being reminded again that all hope for England rested upon her child, and of course her ability to bear a male heir.

The procession went on to St Paul’s Churchyard. In 1512 John Colet had founded a school here, St. Paul’s, which was relocated in 1884. Two hundred schoolchildren put on a display for Anne by the Cathedral, in which they had translated poems into English and gave rapturous praise for both her and Henry. Hall states that Anne ‘highly commended’ the boys’ efforts. This is not surprising. As queen consort, and indeed just prior to her marriage, Anne had offered financial assistance for students, and was involved in the education of not only her ward and nephew, Henry Carey, but also other aristocratic children. As queen she offered refuge to the French humanist, Nicholas Bourbon, and had him educate her nephew and other boys at court. Clearly she took an interest in education; perhaps she found this one of the most interesting and endearing of the displays put on for her.

The procession moved on to Ludgate (so moving in a west direction). Situated on the right of Ludgate Hill (when standing from the end of St Paul’s), there is situated St Martin’s Church. The current church was built by Sir Christopher Wren after the original was destroyed in the fire of 1666. From the rooftops of the church Anne was entertained by a choir of men and children who sang ballads in her honour. After this the procession continued to move west, down Fleet Street. The conduit here was redecorated for her. A Tower was built upon it, with four turrets, from which stood virtues that promised Anne they would never abandon her. And from the middle of this tower came ‘suche seueral solempne instruments, that it semed to be an heauenly noyse, and was muche regarded and praised’.

There are few details about the rest of the procession. It moved down Temple Bar, where another choir greeted Anne here. This appears to be the last display. The next place Anne stopped was Westminster Hall, so the procession probably moved down the Strand. Today Somerset House stands here, the current building dating to the eighteenth-century. The first Somerset House was built in the 1550s and was once occupied by Anne’s daughter, Elizabeth, before she became queen. The procession probably turned left at what is today Trafalgar Square and moved down Whitehall which leads to Westminster Hall. When Anne reached Westminster Hall, she was given refreshments which she shared with her ladies, and gave thanks to those present for the event. Probably exhausted after the long event, especially considering her pregnancy, Anne retired. It seems that she decided to spend the night before her coronation with Henry, for Hall records:

‘And so [Anne] withdrew her selfe, with a fewe ladyes, to the Whitehalle, and so to chamber, and there shifted her, and after went into her barge secretely to the kyng to his Manor of Westminster, where she rested that night’.

For Anne it was probably the perfect end to the perfect day.

Legacy

Anne’s coronation procession has been shrouded by the controversy of her marriage to Henry and by certain contemporary documents which wished to present the event as a disaster. Far from it; the authorities had managed in such a short space of time to organise an impressive and respectable affair. No one publicly booed Anne; as Ives states, those who witnessed the event were more curious about the proceedings than anything else.

However much Anne was disliked by many within London for the simple fact that she replaced Katherine of Aragon, they also appreciated a spectacle. The Imperial ambassador claimed that the Hanseatic merchants had taken the opportunity to publicly insult Anne by displaying the Imperial Eagle within the Holbein display on Gracechurch Street. But Chapuys was wrong, as the eagle displayed was not the double-headed Imperial one of Charles V. For Anne, the procession was a moment of triumph and a chance for her to enact her role as queen consort in such a public space. She did well, with her many gracious speeches and her careful observation of all the displays put on for her. It is impossible to know with precision what Anne felt during this event. But I think exultant and flattered are likely. Perhaps there was also a sense of unease for the entire pageant drew attention to the importance that the child she carried be male. In public both Henry and Anne showed confidence in their belief that they would have sons. What Anne privately felt is up for debate.

Finally, what of Anne’s legacy – what of the ‘golden’ child the ladies at St Paul’s promised she would bear. Well obviously it was not a son, but Elizabeth, who retraced her mother’s footsteps over twenty-five years later during her own coronation procession. As Elizabeth travelled through Fenchurch Street on 14th January 1559, she paused at a series of stages that had been built from one side of a street to the other. On one stage stood representations of her parents, Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn. ‘apparelled with Sceptours & diademes, and other furniture due to the state of a king and quene’, ‘Anne’ and ‘Henry’ greeted a representation of their daughter placed on the forefront stage. What Elizabeth thought of this display we can only guess, though as she moved past this pageant she asked that her chariot may be ‘removed back’ so she could see these representations better and for a little while longer.

I have created an album on the procession on my flickr page:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/20631910@N03/sets/72157623587965011/

Further reading

Primary sources

- The noble tryumphaunt coronacyon of quene Anne (1533) – available to read on Early English Books Online.

- Frederick J Furnivall (ed.), Ballads from Manuscripts: Vol I: Ballads on the condition of England in Henry VIII’s and Edward VI’s Reigns (London, 1868-72), pp.364-401. Contains Hall’s account and all verses composed for the event.

- James M. Osborn (ed.), The Quenes Maiesties Passage through the Citie of London to Westminster the Day before her Coronacion (New Haven, 1960) – this is a contemporary account of Elizabeth I’s coronation. See pp. 33-34 on the representation of her family.

Secondary sources

- Alice Hunt, The Drama of Coronation: Medieval Ceremony in Early Modern England (Cambridge, 2008), pp. 39-76.

- Alice Mary Maitland Hunt, ‘’What art thou, thou idol ceremony?’: Tudor coronations and literary representations, 1509-1559’, PhD diss., Birkbeck (University of London), 2005.

- Eric W. Ives, The life and Death of Anne Boleyn (Oxford, 2004), chps. 12 & 15.

- Gordon Kipling, ‘He That Saw It Would Not Believe It’: Anne Boleyn’s Royal Entry into London’, in Alexandra F. Johnston and Wim Hüsken (eds.), Civic Ritual and Drama (Amsterdam, 1997), pp. 39-79.

- Retha Warnicke, The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn: Family politics at the court of Henry VIII (Cambridge, 1989), pp. 123-130.

Nasim runs an excellent blog on Mary I, see http://mary-tudor.blogspot.com/ and also has a wonderful YouTube channel with lots of Tudor documentaries and goodies – http://www.youtube.com/user/littlemisssunnydale