Thank you to author Loretta Goldberg for visiting us here at the Anne Boleyn Files today as part of the book tour for her debut book, an Elizabethan spy novel called The Reversible Mask which comes out on 3rd December. I have had a sneak peek at it and it’s a wonderful read. I loved the main character, Edward Latham, and the storyline gripped me throughout.

Thank you to author Loretta Goldberg for visiting us here at the Anne Boleyn Files today as part of the book tour for her debut book, an Elizabethan spy novel called The Reversible Mask which comes out on 3rd December. I have had a sneak peek at it and it’s a wonderful read. I loved the main character, Edward Latham, and the storyline gripped me throughout.

Over to Loretta…

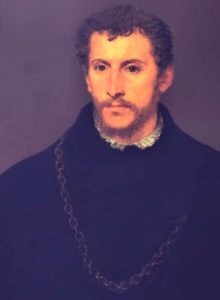

Back in 2013, I was immersed in developing my tale of the tangled relationship between my main character, fictional Sir Edward Latham, and Edmund Campion. Both Catholic subjects of Elizabeth, they acted out their religious convictions in different ways. They met at the pivotal points in their lives, both in England and Europe, and their courses invariably diverged. Late June and early July 1580 were important dates for Campion, for he landed in Dover on 25 June 1580, and within days began the Jesuit mission of conversion and public challenge to the Elizabethan government that led to his execution as a convicted traitor on 1 December 1581. He didn’t plot; he argued. Were his words opinion, incitement or treason?

Son of a London bookseller and Catholic family, Edmund Campion was born on 24 January 1540. An intellectual prodigy, he gave an admired speech to Catholic Queen Mary in 1553 when he was just thirteen, He received a B.A. degree at Oxford in 1560 and took the Oath of Supremacy. Elizabeth was Queen by then, and England had become legally Protestant. Whatever Campion’s yearnings for Catholicism were, he took orders as a deacon in the Anglican Church sometime between 1564 and 1568 (sources differ on the year).

So on 31 August 1566, when Elizabeth began a week-long visit to Oxford as part of her annual royal progress, celebrated scholar and proctor, Edmund Campion, was chosen to argue for the Crown as Queen’s champion in the Latin debates. He addressed Queen, court, special guest Gusman de Silva, the Spanish ambassador, and the Oxford community. Stepping on stage at St. Mary’s Hall, he began, “One thing only reconciles me to the unequal contest I must maintain single-handed against four pugnacious youths; that I am speaking in the name of Philosophy, the princess of letters, before Elizabeth, the lettered princess.”

In his proposition he amalgamated science, classical astronomy and mythology, couching his logic in the language of tribute. “The tides are caused by the moon’s motions. Further, the lower bodies of the universe are regulated by the higher, the highest of which, in the sublunary sphere, is the moon. At the peak of the sublunary sphere is the moon goddess, who therefore regulates the moon and all below.” Since Elizabeth was often called Cynthia, moon goddess, Campion was implying that his sovereign was a prime mover in the cosmos. Despite the custard-thick flattery and fanciful logic, his argument turned out to be impossible to dismantle.

In his proposition he amalgamated science, classical astronomy and mythology, couching his logic in the language of tribute. “The tides are caused by the moon’s motions. Further, the lower bodies of the universe are regulated by the higher, the highest of which, in the sublunary sphere, is the moon. At the peak of the sublunary sphere is the moon goddess, who therefore regulates the moon and all below.” Since Elizabeth was often called Cynthia, moon goddess, Campion was implying that his sovereign was a prime mover in the cosmos. Despite the custard-thick flattery and fanciful logic, his argument turned out to be impossible to dismantle.

The first opponent argued that the lower bodies regulated the higher. He cited an ancient theory that the heavens were formed by distilling corrupt earth and water into the purer air and fire, which in turn improved the earth. “Meteors are expulsions of earth’s gross matter,” he stated.

The next contestant proposed that as the higher and lower bodies never touched, it was not provable that they acted on each other. The final contestant argued that all the others were wrong. Citing Renaissance scholar Paracelsus, he said that the four humours governed mind, matter, and the firmament, not the moon.

The moderator declared that no one had disproved Campion’s proposition that the tides were caused by the moon’s motions, therefore he won. He also won an impromptu Latin debate on “Fire” the next day. Both Leicester and Cecil offered him patronage.

My fictional character, young courtier Sir Edward Latham, was at this performance. Unlike Campion, he knew his doctrinal convictions, and was finding it impossible to reconcile his faith with fidelity to a heretical state. With intellectuals like Campion becoming Protestantism, he saw no space for a covert Catholic like him. Latham decided to throw everything up—status, family and wealth—to serve Catholic monarchs abroad.

They did not meet again for seven years. Latham spent those years spying for Catholic Spain against French Huguenots and the Dutch Protestant rebels. He avoided any direct action against England, but fought in one battle. Unsettling dreams about the scale of Catholic violence in Europe were beginning to plague him, but he was fixed in his doctrinal beliefs.

Campion eventually rethought his Protestant allegiance, leaving Oxford in 1568 to be a scholar in Ireland. Suspected of Catholic sympathies in the aftermath of the 1569 Catholic rebellion against Elizabeth, he fled to Douai. He announced his conversion and took a Bachelor of Divinity degree granted by the University of Douai.

The Campion Latham met in Douai was implacable. This was the man who wrote to his old mentor in England, Richard Cheney, Bishop of Gloucester, a compromising Catholic. “Wherein lies your hope?… Because of all heresiarchs you are the least crazy?… Because you are hospitable to your townspeople and to good men? Because you plunder not your palace and lands as your brethren do? Surely, these things will avail you if you return to the bosom of the Church…But now whilst you are a stranger and an enemy, while like a base deserter you fight under an alien flag, it is in vain to attempt to cover your crimes with the cloak of virtue. You shall gain nothing, except perhaps to be tortured somewhat less horribly in the everlasting fires than Judas or Luther or Zwinglius, or those antagonists of yours, Cooper, Humphrey and Samson…” He warned that after the Catholic reforms of the Council of Trent one must be altogether within the house of God. The tiniest deviation and a man was anathema. He wallowed in line after line of graphic depictions of hell’s tortures if Cheney didn’t convert. Of course, he went on at length because he was desperate to save a friend. But that care doesn’t lessen the feral quality of his spirituality. (Source: Richard Simpson Edmund Campion A Biography, Williams and Norgate, London1867, n p.363).

Campion could have taught in Douai as he had at Oxford. He was charismatic and students loved him. But he wanted to be a Jesuit. The order’s founder, Ignatius Loyola, had said: if His Holiness names something black, which members of our society see as white, then they must, in like manner, term it black. This was the certainty Campion craved.

Against this background, Jesuit Edmund Campion prepared to return, with the understanding that he would avoid challenging Elizabeth on her own land. To make sense of how he acted in England, it is worth considering the timeline of his stop in Geneva on the way.

Geneva was the headquarters of Calvinist leader Theodore Beza. Campion, with a party of priests, had been promised the freedom of the city after an examination by a magistrate. After dinner on the first day, Campion and several Jesuit companions sought Beza out at home, saying that they wished to discuss doctrinal differences between Protestants and Puritans, since Elizabeth abhorred Puritans, whose doctrines seemed close to Beza’s Calvinism. Beza’s wife Candida answered the door. She was an object of curiosity and merriment to the priests, since they knew she’d been a Parisian tailor’s wife before running away with Beza. A grumpy Beza came down from his study and a discussion began. Campion’s goal was to drive a wedge between Beza and Elizabeth. When he began to expound the substantial contradictions between the Anglican hierarchical church and Calvinism, Beza signalled his wife to get him out of there. He sent students to meet the Jesuits. Discussions and dining went on until midnight. Then things escalated. Frustrated that Beza was eluding them, the Jesuits challenged him to debate any disputed point in public in front of neutral judges, with the condition that the loser would be burnt alive in public at the stake. Intellectual disputation was to morph into a debating dance of death.

In my novel, Edward Latham, meets Campion in a quiet Calais cemetery, to give him money and contacts for his English mission. He was still serving Spain exclusively, his spymaster being Don Juan de Idiaquez, Secretary of State, though his doubts are growing. There was an additional complication. A Papal/Spanish expedition to support Irish Catholic rebels against Elizabeth was about to set sail. Philip wanted the Jesuits to keep a low profile. Latham expressed his disapproval of Campion’s blatancy in Geneva.

Adapted excerpt:

He tugged Latham’s arm, eyes sparkling. “Firstly: the English queen rules her church with a strict hierarchy. Secondly: Calvinism considers church hierarchy anathema. Therefore, thirdly: the English queen is a heretic to Protestants as well as Catholics. It’s unbreakable. The chance to publicly debate the leader of the Calvinist heretics was irresistible! Our superiors didn’t say to avoid challenging Elizabeth everywhere; just in her own lands. Geneva is not England. It was a great caper. How could we lose?”

He released Latham and leaned against the tree, laughing. “We had logic on our side. Tactics favoured us, too. If Beza refused our challenge, he’d be shamed in front of his students, a beaten dog slinking into shadow. If he took the challenge and we won, smoke would have risen over Satan’s greatest ally since Luther! Elizabeth’s lustre tarnished, whatever the verdict. And if we lost, then we weren’t worthy messengers of God. He would have clasped three cleansed souls to His merciful bosom.

“Anyway, Beza’s wife clapped a stopper on the whole thing. What kind of holy man hides behind a woman? She ran out, the wife, carrying piles of paper, shouting he had work to do then dragged him bodily upstairs. How we laughed. He sent students to debate us. They weren’t bad fellows, but they were just students, so we didn’t press the idea of a burning. Once I touch English soil, I’ll preach giving Elizabeth her due in temporal matters.”

“You’re naïve,” Latham snapped. “If I’ve heard the story, so has the English privy council. They won’t distinguish between challenging Elizabeth outside and inside their borders.”

“Look,” Campion said, suddenly sombre. “I’m a scared sinner like everyone else. I’d rather make converts on this side of the Channel; I did well in Prague. But my orders are to minister to the faithful and educate the willing in England, which is the Church’s greatest need. There’s been a generation of quiet under Elizabeth. As Catholics die, theology is forgotten. A nation slumbers unaware towards perdition. I must do what I can to turn its fate.

“His Holiness says we may urge English Catholics to give Caesar, Elizabeth, her due in temporal matters, to obey her until the Vatican directs otherwise. What could the privy council object to now, that’s not purely doctrinal? I can offer such comfort that I ache to begin, including to your sister.”

Latham sighed. “Gregory’s neutral directive justifies my handing you the jewels and contacts. My task is done. But listen to what you’ve said. Think about how Elizabeth will interpret it. The Vatican’s not compromising; it’s playing for time. English Catholics shouldn’t rebel now, all passion and no plan. No. They should wait for orders, presumably given when missionary priests like you have converted enough of the nobility to papal allegiance to be able to defeat the government. It’s not whether to rebel, it’s when. You ask what the privy council could object to. Gregory aims to nurse opposition into viable life. That’s what they’ll object to. Your tautology is gossamer.

“Think on it another way. If you were a man who sowed your fields, walking up and down the muddy furrows, dropping the seeds into the hungry earth, watering your seeds if times were dry, spreading the richest dung to help them grow; and your brother, with a stronger back, harvests, aren’t you both equally engaged in bringing ripe crops to market?”

Campion rebuffed this concern, warning Latham to look to his own soul, which he knew was beset by doubt. Latham’s last glimpse of Campion was his back, as he bent to pick wildflowers from a roadside ditch before strolling to the harbour to find a boat to Dover.

The crux of their argument still bedevils us, particularly with the power of social media.

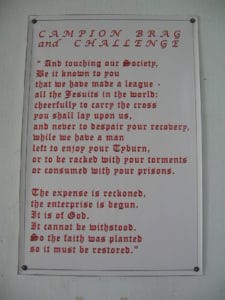

Campion’s mission began quietly, but by September he’d written his famous “Brag,” titled Address to the Lords of the Privy Council. He sent his letter to Europe, where it was printed then smuggled back. It circulated privately but widely, bringing its author instant fame. He’d gone public.

Campion’s mission began quietly, but by September he’d written his famous “Brag,” titled Address to the Lords of the Privy Council. He sent his letter to Europe, where it was printed then smuggled back. It circulated privately but widely, bringing its author instant fame. He’d gone public.

After explaining that his mission was to cry alarm spiritual against foul vice and proud ignorance besetting his co-nationals, Campion challenged the entire Elizabethan establishment. He demanded public debates on theology in front of the Lords in Council and the Heads of both Houses of Parliament, in which he would prove England had a faulty relationship between Church and State; at both Oxford and Cambridge Universities, where he promised to prove the truth of the Catholic faith; and in front of the Courts Spiritual and Temporal, where he would justify primary allegiance to Pope over Crown. He demanded an audience with Elizabeth, to correct her misguided beliefs.

The map shows the problem:

Campion justified primary allegiance to Rome, while a Papal/Spanish army of five to six hundred men had taken Smerwick, Irish territory ruled by England, and an English force of ships and men was trying to take it back. Privy councillors who had to counter Campion’s words were also repelling an invasion.

Unable to find Campion, the English government rebutted the Brag with published counter-arguments that were quickly mocked by Catholics abroad. Still, Campion wasn’t preaching rebellion. He was demanding to argue doctrine to a conclusion. There were legal precedents for changing religious law after public debate; Elizabeth’s church had been created by Parliament after debates. Campion might have thought he’d found his legal loophole. But his radical intent was clear.

Nine months later, he escalated.

The second pamphlet’s title was Ten Reasons; ten proofs of Protestant heresy. It was secretly published in England. Campion arranged to put this tract on the seats of St Mary’s Hall, Oxford, before graduation ceremonies for four hundred degree recipients. Many of these graduates were going into government, due to take the Oath of Allegiance to Elizabeth, which they couldn’t do if they accepted Campion’s logic. After arguing that Protestant theology was self-contradictory, he insisted that Heaven couldn’t hold both Calvinist and Catholic monarchs. On top of the Brag’s ‘cry alarm spiritual against foul vice and proud ignorance’ besetting English citizens, he was implying that they were in danger of damnation. And by putting his tract in the hands of new graduates, he was demanding that they make choices he hadn’t been ready to make at their age. 27th June 1581, Campion came full circle: St. Mary’s Hall was where he’d debated as Elizabeth’s champion in 1566. At St. Mary’s Hall, he threw down his final gauntlet.

The hunt for him intensified, and he was captured. Torture, trial and a traitor’s death followed. He got his debates, but as part of the interrogation and trial process, not public. The international response at the time was repugnance at Elizabethan cruelty, especially as Campion and his fellow infiltrators hadn’t fomented a current rebellion or plotted assassination. “You imbue your cause with viciousness,” English spy Anthony Standen wrote to Walsingham, adding that moderate Catholic foreign princes would have been keener on an alliance had English policies been milder.

My fictional Edward Latham reacted in the opposite way. Campion’s implacability had shown him how truly dangerous Jesuit and Spanish activities were to his birth country and family. He decided to become a double agent from then on, and to use his spying for both sides to buttress the current balance of power. Campion was beatified in 1886 and canonised in 1970, four hundred years after Elizabeth’s excommunication.

The Reversible Mask: An Elizabethan Spy Novel

Summer 1566. A glittering royal progress approaches Oxford. A golden age of prosperity, scientific advances, exploration and artistic magnificence. Elizabeth I’s Protestant government has much to celebrate.

But one young Catholic courtier isn’t cheering.

Conflicting passions—patriotism and religion—wage war in his heart. On this day, religion wins. Sir Edward Latham throws away his title, kin, and country to serve Catholic monarchs abroad.

But his wandering doesn’t quiet his soul, and when Europe’s religious wars threaten his beloved England and his family, patriotism prevails. Latham switches sides and becomes a double agent for Queen Elizabeth. Life turns complicated and dangerous as he balances protecting country and queen, while entreating both sides for peace.

Intrigue, lust, and war combine in this thrilling debut historical novel from Loretta Goldberg.

Editorial reviews:

“This is a glorious novel! Rich in detail and atmosphere, jewel-like in its creation of Elizabethan England, it’s the best kind of historical fiction, transporting readers to a captivating time and place and story. Goldberg does a magnificent job of conveying the intrigue, passion and sometimes sheer sumptuousness of Elizabeth – I’s court and politics. I loved it.” – Jeanne Mackin, award winning author.

“Goldberg has created a richly detailed world, brought to life with a brilliant cast of engaging characters. The Reversible Mask is a true delight.” – Adrienne Dillard, author of Cor Rotto.

Click here to find out more about Loretta’s book or to pre-order it as a kindle or paperback. It can be read for free if you have Kindle Unlimited.

The Historical Novel Society New York Chapter are holding a book launch event on 18th December for The Reversible Mask. It’s in the Willa Cather Community Room at Jefferson Markey Library, 425 Ave of the Americas at 10th St, New York, at 6-8pm, and is free and open to the public. There will be a reading, a slideshow, a Q&A, and refreshments.

Loretta

An Australian-American, I earned a BA in English Literature, Musicology and History at the University of Melbourne, Australia. After teaching English Literature at the Department of English for a year, I risked all, coming to the USA on a Fulbright scholarship to study piano with Claudio Arrau. My discography consists of nine commercial recordings, now in over seven hundred libraries. I was lucky to premier an unknown work by Franz Liszt on an EMI HMV (Australian Division) album, and my edition of the score for G. Schirmer is in its third edition. Concurrently, I built a financial services practice, which I sold recently to focus on writing. My published non-fiction pieces consist of articles on financial planning, arts reviews and political satire. I earned an MA (music performance) from Hunter College, New York; and a Chartered Life Underwriter degree from the American College, Pennsylvania. Member of the Historical Novel Society, New York Chapter, I started and run their published writer public reading series at the landmark Jefferson Market Library.

An Australian-American, I earned a BA in English Literature, Musicology and History at the University of Melbourne, Australia. After teaching English Literature at the Department of English for a year, I risked all, coming to the USA on a Fulbright scholarship to study piano with Claudio Arrau. My discography consists of nine commercial recordings, now in over seven hundred libraries. I was lucky to premier an unknown work by Franz Liszt on an EMI HMV (Australian Division) album, and my edition of the score for G. Schirmer is in its third edition. Concurrently, I built a financial services practice, which I sold recently to focus on writing. My published non-fiction pieces consist of articles on financial planning, arts reviews and political satire. I earned an MA (music performance) from Hunter College, New York; and a Chartered Life Underwriter degree from the American College, Pennsylvania. Member of the Historical Novel Society, New York Chapter, I started and run their published writer public reading series at the landmark Jefferson Market Library.