A big welcome to author and historian Toni Mount who is joining is today for the final stop of her blog/book tour for the launch of her latest historical novel. The Colour of Murder is the latest whodunit in the popular ‘Sebastian Foxley’ series of medieval murder mysteries and it’s a wonderful read.

A big welcome to author and historian Toni Mount who is joining is today for the final stop of her blog/book tour for the launch of her latest historical novel. The Colour of Murder is the latest whodunit in the popular ‘Sebastian Foxley’ series of medieval murder mysteries and it’s a wonderful read.

Over to Toni…

540 years ago, on the 18th February 1478 the Duke of Clarence was, famously, drowned in a butt of malmsey wine. Did he jump or was he pushed? The question has never been answered, so this was an opportunity for the intrepid investigator Seb Foxley – to finally solve the mystery.

If someone was found to be criminally insane, even in the fifteenth century a possible outcome was to be sent to Bedlam Hospital.

In the thirteenth century, Simon FitzMary, whose origins are obscure, rose to become one of the two Sheriffs of London, serving in that office twice, though he never made it to the top as Mayor. Simon was a pious man with a particular devotion to the Virgin Mary and, more unusually, to the Star of Bethlehem. The reason why he venerated the star – so the story goes – is that while he was on Crusade in the Holy Land with Richard the Lionheart, he became lost one night, all alone and in danger of straying into the enemy’s camp. Suddenly, a bright star appeared in the sky and guided him back to his companions. Simon was certain this was the Star of Bethlehem, the same one that had led the three Wise Men to visit the Christ Child.

On returning home to London, Simon became a wealthy man and determined upon a charitable act in thanksgiving to God for having sent the Star of Bethlehem to rescue him. He donated a plot of land outside Bishopsgate to the Bishop of Bethlehem, so that a priory and hospital could be founded for the benefit of the poor. In 1247, the small Priory of St Mary of Bethlehem was built and devoted to the care of the sick. It became known as Bethlehem Hospital and used the sign of the Star as its badge. Local folk soon abbreviated the name to ‘Bethlem’ which became ‘Bedlam’.

The priory hospital was a single storey building on a plot of two acres which became known as ‘St Mary [Ho]spital Fields’ and eventually Spitalfields. There was a central courtyard and a chapel where both monks and patients prayed. There were twelve separate cubicles, rather like monks’ cells, for the patients, as well as accommodation for the Infirmerer in charge and the religious brothers who cared for the sick. A separate kitchen provided meals and a small garden not only supplied produce for the kitchen but was a place where patients could exercise and, if they were well enough, even tend the plants or do a bit of weeding. The hospital remained at Bishopsgate until 1676 when it became too cramped and small for the number of patients and was moved to Moorfields. Today, the original site lies beneath Liverpool Street Railway Station.

At some point, quite early in the hospital’s history, the monks began to accept patients suffering symptoms of mental illness, rather than physical disabilities or disease. No one understood these ‘invisible’ ailments: no fever, no rashes, no pain; but anguish, misery and, perhaps, outbursts of inexplicable behaviour. Although most sufferers of such problems would have remained at home, for those without family members to care for them, or if they became too unstable and violent to remain in the community, then Bedlam was their only refuge. By 1346, a hundred years after its foundation, the hospital was struggling to survive on the financial bequests left by Simon FitzMary but its services were recognised as vital, so the Mayor and Aldermen of the City of London agreed to take it over. From then on, it specialised in the treatment of ‘madness’, although we now know that among its patients were those with learning difficulties, epilepsy – or the ‘falling sickness’ as it was then called – severe depression and various forms of dementia; people who weren’t ‘mad’ at all. There is a possibility that patients from a similar asylum known as Stone House by the Eleanor Cross at Charing – now Charing Cross – were moved to Bedlam Hospital in the 1370s. By 1403, all the patients there were reckoned to be ‘mad’, as noted in a scandalous event that year. The hospital treasurer, Peter Taverner (aka Peter the Porter), was found guilty of stealing from the charitable funds and the theft of both hospital property and the belongings of the six male patients, all of whom were mente capti i.e. ‘insane’.

Because mental illness was so hard to explain, unsurprisingly, medieval people saw it as a punishment for sin, sent from God but it could be unclear who was being punished: the victim, their family or the community? If the patient was the sinner, then their treatment should consist of physical punishment and the hospital inventory of equipment included manacles, shackles and a set of stocks, all used to detain and deter criminals. The pain and shock were believed to cure certain conditions. Confession of sins, penance and prayer were more kindly treatments often used as the first resort and then, if the patient didn’t recover, in conjunction with the corporal punishments. If neither of these ‘treatments’ helped, then isolation might well help the patient ‘come to their senses’, or so it was thought.

However, suppose it wasn’t the patient who had sinned but they were being punished by God on behalf of others who had transgressed? This was believed to be perfectly feasible, in which case, the victim was considered holy. Epileptics were thought to be ‘inspired’ by God and the stories of many saints who had seen visions and behaved strangely might well have been reckoned ‘mad’ at the time. This was a conundrum so, just in case the ‘mad’ person was holy, it was a religious duty to care for and show compassion for those afflicted.

Although few mentally ill people were ever put into such a place, Bedlam was regarded as the specialised long-term solution for the problem of what to do with those who were ‘insane’. The image of ‘Bedlam’ gave a new word to the English language, to describe a chaotic, noisy and irrational situation. Medieval Bedlam was probably a haven of peace compared to what it became in its later situation at Moorfields in the eighteenth century. There, the treatment was often inhumane. Visitors could pay for a tour, to view naked patients raving or staring at nothing, being beaten or confined in strait-jackets. They were encouraged to laugh at those who crawled like animals on all fours or claimed that they were John the Baptist returned.

In 1930, the Bethlem Royal Hospital, as it is now correctly called, was moved to the south London suburb of Bromley. It has 350 beds for patients with mental health problems and the Star of Bethlehem remains as the hospital logo today. We still have difficulty understanding and explaining some of these problems but at least we are more humane in dealing with them.

Trivia from Claire: Did you know that on 27th July 1529 George Boleyn, brother of Anne Boleyn, was appointed Governor of Bethlehem (Bedlam) Hospital? He remained governor until his execution in May 1536.

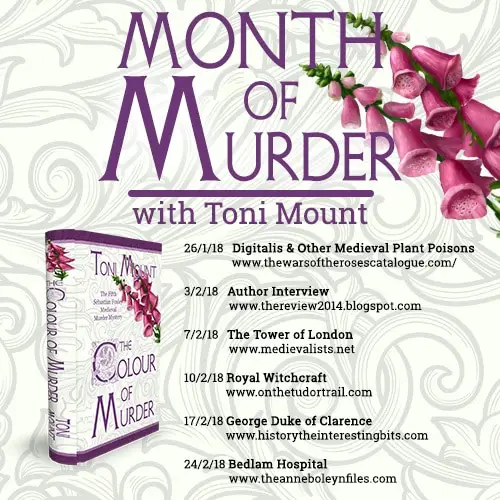

If you missed the other stops on Toni’s book tour then do visit them at the blogs listed above.

Toni Mount is a popular writer and historian; she is the author of Everyday Life in Medieval London and A Year in the Life of Medieval England (pub Amberley Publishing) and several of the online courses for www.medievalCourses.com. Her successful ‘Sebastian Foxley’ series of medieval whodunits is published by MadeGlobal.com and the latest book in this series The Colour of Murder is now available as a paperback or on Kindle – http://getbook.at/colour_of_murder

The Colour of Murder

In February 1478, London is not a safe haven, whether for princes or commoners. A wealthy merchant is killed by an intruder; a royal duke dies at the Tower but in neither case is the matter quite as it seems. Seb Foxley, an intrepid young artist, finds himself in the darkest of places, fleeing for his life. With foul deeds afoot at the king’s court, his wife Emily pregnant and his brother Jude’s hope of marrying Rose thwarted, can Seb unearth the secrets which others would prefer to keep hidden?

In February 1478, London is not a safe haven, whether for princes or commoners. A wealthy merchant is killed by an intruder; a royal duke dies at the Tower but in neither case is the matter quite as it seems. Seb Foxley, an intrepid young artist, finds himself in the darkest of places, fleeing for his life. With foul deeds afoot at the king’s court, his wife Emily pregnant and his brother Jude’s hope of marrying Rose thwarted, can Seb unearth the secrets which others would prefer to keep hidden?

Join Seb and Jude, their lives at hazard in the dangerous streets of the city, as they struggle to solve crimes and keep their business flourishing in this new Sebastian Foxley medieval murder mystery: The Colour of Murder. Click here to find the book on your country’s Amazon site.

Free e-book – The Foxley Letters

The Foxley Letters – An exclusive collection of letters. This unique e-book in the bestselling Sebastian Foxley Medieval Murder Mystery Series is free to download. With personal letters from all the main characters, including Seb, Emily, Jude and even the wonderful Jack, this collection of letters will add to the lives and stories of those involved in the intrigue, drama and excitement of these historical thrillers set in Medieval London. You can download it at www.madeglobal.com/authors/toni-mount/download/

The Foxley Letters – An exclusive collection of letters. This unique e-book in the bestselling Sebastian Foxley Medieval Murder Mystery Series is free to download. With personal letters from all the main characters, including Seb, Emily, Jude and even the wonderful Jack, this collection of letters will add to the lives and stories of those involved in the intrigue, drama and excitement of these historical thrillers set in Medieval London. You can download it at www.madeglobal.com/authors/toni-mount/download/

You can follow Toni and her work at: