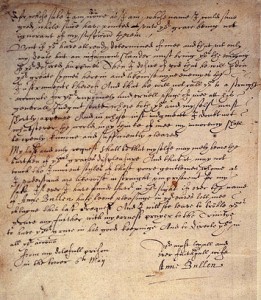

On 6th May 1536, it is said that Anne Boleyn wrote the following letter to her husband, King Henry VIII, from the Tower of London:

On 6th May 1536, it is said that Anne Boleyn wrote the following letter to her husband, King Henry VIII, from the Tower of London:

“To the King from the Lady in the Tower” [Heading said to have been added by Thomas Cromwell]

“Sir, your Grace’s displeasure, and my Imprisonment are Things so strange unto me, as what to Write, or what to Excuse, I am altogether ignorant; whereas you sent unto me (willing me to confess a Truth, and so obtain your Favour) by such a one, whom you know to be my ancient and professed Enemy; I no sooner received the Message by him, than I rightly conceived your Meaning; and if, as you say, confessing Truth indeed may procure my safety, I shall with all Willingness and Duty perform your Command.

But let not your Grace ever imagine that your poor Wife will ever be brought to acknowledge a Fault, where not so much as Thought thereof proceeded. And to speak a truth, never Prince had Wife more Loyal in all Duty, and in all true Affection, than you have found in Anne Boleyn, with which Name and Place could willingly have contented my self, as if God, and your Grace’s Pleasure had been so pleased. Neither did I at any time so far forge my self in my Exaltation, or received Queenship, but that I always looked for such an Alteration as now I find; for the ground of my preferment being on no surer Foundation than your Grace’s Fancy, the least Alteration, I knew, was fit and sufficient to draw that Fancy to some other subject.

You have chosen me, from a low Estate, to be your Queen and Companion, far beyond my Desert or Desire. If then you found me worthy of such Honour, Good your Grace, let not any light Fancy, or bad Counsel of mine Enemies, withdraw your Princely Favour from me; neither let that Stain, that unworthy Stain of a Disloyal Heart towards your good Grace, ever cast so foul a Blot on your most Dutiful Wife, and the Infant Princess your Daughter.

Try me, good King, but let me have a Lawful Trial, and let not my sworn Enemies sit as my Accusers and Judges; yes, let me receive an open Trial, for my Truth shall fear no open shame; then shall you see, either mine Innocency cleared, your Suspicion and Conscience satisfied, the Ignominy and Slander of the World stopped, or my Guilt openly declared. So that whatsoever God or you may determine of me, your Grace may be freed from an open Censure; and mine Offence being so lawfully proved, your Grace is at liberty, both before God and Man, not only to execute worthy Punishment on me as an unlawful Wife, but to follow your Affection already settled on that party, for whose sake I am now as I am, whose Name I could some good while since have pointed unto: Your Grace being not ignorant of my Suspicion therein.

But if you have already determined of me, and that not only my Death, but an Infamous Slander must bring you the enjoying of your desired Happiness; then I desire of God, that he will pardon your great Sin therein, and likewise mine Enemies, the Instruments thereof; that he will not call you to a strict Account for your unprincely and cruel usage of me, at his General Judgement-Seat, where both you and my self must shortly appear, and in whose Judgement, I doubt not, (whatsover the World may think of me) mine Innocence shall be openly known, and sufficiently cleared.

My last and only Request shall be, That my self may only bear the Burthen of your Grace’s Displeasure, and that it may not touch the Innocent Souls of those poor Gentlemen, who (as I understand) are likewise in strait Imprisonment for my sake. If ever I have found favour in your Sight; if ever the Name of Anne Boleyn hath been pleasing to your Ears, then let me obtain this Request; and I will so leave to trouble your Grace any further, with mine earnest Prayers to the Trinity to have your Grace in his good keeping, and to direct you in all your Actions.

Your most Loyal and ever Faithful Wife, Anne Bullen.

From my doleful Prison the Tower, this 6th of May.”1

The letter first appeared in Lord Edward Herbert’s 1649 book The Life and Raigne of King Henry the Eighth”.2 Herbert was sceptical, believing that the letter may have been a fake penned in the reign of Elizabeth I, but Gilbert Burnet, Bishop of Salibury,3 writing in 1679, believed it to be genuine. It was claimed that the letter was found with Sir William Kingston’s letters in Cromwell’s papers and, like Kingston’s letters to Cromwell, it had been damaged during the Ashburnam House fire of 1731.

This letter has often been considered a forgery, mainly due to the handwriting which differs from other authenticated letters by Anne. However, at the time of publication, the claim was made that the letter found was a copy made by Cromwell. This would explain why it was not in Anne’s handwriting. Although Burnet and Victorian historian J.A. Froude4 believed that the letter was authentic, historians such as Agnes Strickland and James Gairdner thought it to be a forgery, with Gairdner5 believing it to be written in an Elizabethan hand. Other historians, like Paul Friedmann and P W Sergeant, also thought it to be a forgery. Modern day historian Alison Weir6 makes a further point when she draws our attention to Henry Savage’s view. Savage states that the difference in handwriting could be due to this letter being written a decade later than Anne’s other authenticated letters, which date from the 1520s, and also the fact that she was imprisoned and living in fear of her life. Weir also cites Jasper Ridley, editor of The Love Letters of Henry VIII,7 as pointing out that the letter “bears all the marks of Anne’s character, of her spirit, her impudence and her recklessness”.

There are, however, anomalies which suggest that the letter is a forgery:

- The signature “Anne Bullen” rather than the usual “Anne Boleyn”, “Anne de Boulaine” or “Anne the Queen”.

- The fact that Cromwell kept it rather than destroying it.

- The heading at the top: “To the King from the Lady in the Tower” – wouldn’t Cromwell have referred to her as the Queen or as Anne Boleyn? “The Lady in the Tower” is rather poetic and romantic.

- The style, which is not consistent with Anne’s other letters.

- The reproving tone and provocative content – The writer is claiming that the King instigated the plot so that he could marry Jane Seymour. Would Anne risk angering and insulting Henry in this way?

BUT these anomalies can be thrown out of the window:

- If the letter was a copy then this could have been Cromwell referring to Anne.

- It wasn’t discovered until the 17th century so it was obviously kept hidden and not made public.

- Perhaps Cromwell no longer saw her as Queen and nicknamed her “The Lady in the Tower”.

- Anne was not writing a normal letter, she had the shadow of the axe (or rather, sword) hanging over her.

- Anne could be provocative when she wanted to be. It may have been a huge risk to take but perhaps she wanted this one opportunity to tell the King what she thought of him and his plot.

- The handwriting issue and the use of “Bullen” can also be explained away. The letter could have been a copy made by Cromwell. It could be, as argued by Jasper Ridley,8 a late 16th century copy of the earlier original, or Anne may have been so distraught that she dictated it to one of her ladies.

Ultimately, there is no way we can be certain one way or the other, but I hope that Anne did write it or something like it. Anne’s execution speech stuck to the usual rules, in that she accepted her sentence and praised the King, but I’d like to think that Anne had some opportunity to let the King know what she really thought.

(From The Fall of Anne Boleyn: A Countdown by Claire Ridgway)

Notes and Sources

- Smeeton, G (1820) The Life and Death of Anne Bullen, Queen Consort of England.

- Herbert, E (1649) The Life and Raigne of King Henry the Eighth.

- Burnet, G (1865) The History of the Reformation of the Church of England.

- Froude, J A (1891) The Divorce of Catherine of Aragon: The Story as Told by the Imperial

Ambassadors Resident at the Court of Henry VIII. - LP x. 808

- Weir, A (2009) The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn, 173.

- The Love Letters of Henry VIII, ed. Ridley, Jasper (1989)

- Ibid.