A big welcome to Seamus O’Caellaigh who visits us today as part of the book tour for his wonderful new book Pustules, Pestilence and Pain: Tudor Treatments and Ailments of Henry VIII. Here is an article based on an extract from his book about a complaint that Henry VIII suffered in 1539 and how it would have been treated.

A big welcome to Seamus O’Caellaigh who visits us today as part of the book tour for his wonderful new book Pustules, Pestilence and Pain: Tudor Treatments and Ailments of Henry VIII. Here is an article based on an extract from his book about a complaint that Henry VIII suffered in 1539 and how it would have been treated.

Over to Seamus…

Modern people do not like talking about using the bathroom, and especially avoid talking about issues with constipation, haemorrhoids or diarrhoea. The king, however, had no privacy, and his movements were never inconspicuous. In fact, he had a ‘Groom of the Stool’ who oversaw his most private business. In 1539, his constipation appeared to be more than just a minor issue, and the issues were recorded by the most intimate of his courtiers.

During Henry’s 36-year reign, he had four Grooms of the Stool. From 1509 to 1526 the role was taken by Sir William Compton. Sir William was knighted during this time and also acted as an Under-Treasurer of the Exchequer, Chancellor of Ireland and sheriff of a few regions. After Sir William, came Sir Henry Norris, who was Groom of the Stool for ten years. His term ended with his execution as one of the four men found guilty with Queen Anne Boleyn and her brother. Sir Thomas Heneage then held the office for a decade, followed by Sir Anthony Denny for just two years, as the king passed away in 1547.

The following letter was written by Sir Thomas Heneage, Groom of the Stool, to Thomas Cromwell in September 1539:

“I received your letter this morning, although your servant came over night; ‘for by th’advice of the physicians the King’s Majesty went betimes to bed, whose Highness slept until two of the clock in the morning, and then his Grace rose to go to the stool which, by working of the pills and glister that his Highness had taken before, had a very fair siege, as the said physicians have made report; not doubting but the worst is past by their perseverance, to no danger of any further grief to remain in him, and the hinder part of the night until 10 of the clock this morning his Grace had very good rest, and his Grace findeth himself well, saving his Highness saith he hath a little soreness in his body. And I would have had his said Majesty to have read your letter, but would that I should make to him relation thereof, whereat his Grace smiled, saying that your Lordship had much more fear than required.’ I will send your bills as soon as his Grace has signed them. The long tarrying of your servant here was by my command. Hampthill, Friday, between 10 and 11 a.m.”1

With the diet that Henry ate, it is no wonder that he had some digestive issues. Henry, of course, was not the only one eating at the Tudor court. In one year, meat consumption totalled 1,240 oxen, 8,200 sheep, 2,330 deer, 760 calves, 1,870 pigs and 53 wild boars and they drank 600,000 gallons of beer. A Declaracion of the Particular Ordinances of Fares for the Dietts to be served to the King’s Highnesse, the Queen’s Grace, and the sides, with the Household2 shows that an awful lot of meat and not enough fibre were consumed at Henry VIII’s court. It is no wonder he was troubled by constipation.

In my book, I include a recipe for a ‘glyster’, or enema, from Bullein’s Bulwarke of Defence by William Bullein. Bullein talks of using dock, a broad-leaved wayside plant with large tap-roots, or rumex, for a glyster being sodden. He says it will move the belly to be laxative. The fluid for the glister should be made like a decoction, or boiled mash, and the plant product strained from the remaining water. Then the fluid is placed in the pig bladder, another bag, or a syringe. The bag is attached to a tube and the tube inserted into the rectum. The bag is then squeezed, forcing the fluid into the rectum.

In my book, I include a recipe for a ‘glyster’, or enema, from Bullein’s Bulwarke of Defence by William Bullein. Bullein talks of using dock, a broad-leaved wayside plant with large tap-roots, or rumex, for a glyster being sodden. He says it will move the belly to be laxative. The fluid for the glister should be made like a decoction, or boiled mash, and the plant product strained from the remaining water. Then the fluid is placed in the pig bladder, another bag, or a syringe. The bag is attached to a tube and the tube inserted into the rectum. The bag is then squeezed, forcing the fluid into the rectum.

Dioscorides wrote about the types of dock and that “all of these (boiled) soothe the intestines.”3 However, the process of an enema without a herb or chemical other than a natural saline, will have a desired effect just by filling the rectum with fluid, expanding out the walls of the rectum, and making it easier for the stool to move.

When researching this treatment, I assumed that the dock had little to do with the treatment, however, on further investigation, I found that it contains anthraquinone.4 “Besides their utilization as colourants, anthraquinone derivatives have been used for centuries for medical applications, for example, as laxatives and antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory agents. Current therapeutic indications include constipation, arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and cancer.”5 It appears that this treatment, along with laxative pills made from myrobalan, aloe and scammony (recipe also by Bullein), could very well have been the reason for Henry’s “very fair siege”.

Pustules, Pestilence, and Pain

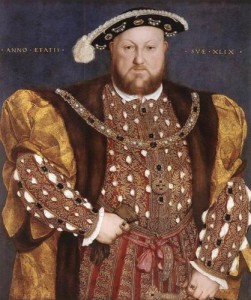

Henry VIII lived for 55 years and had many health issues, particularly towards the end of his reign.

Henry VIII lived for 55 years and had many health issues, particularly towards the end of his reign.

In Pustules, Pestilence, and Pain, historian Seamus O’Caellaigh has delved deep into the documents of Henry’s reign to select some authentic treatments that Henry’s physicians compounded and prescribed to one suffering from those ailments.

Packed with glorious full-colour photos of the illnesses and treatments Henry VIII used, alongside primary source documents, this book is a treat for the eyes and is full of information for those with a love of all things Tudor. Each illness and accident has been given its own section in chronological order, including first-hand accounts, descriptions of the treatments and photographic recreations of the treatment and ingredients.

You can click here to find out more about the book.

Author Bio

Seamus O’Caellaigh has always been interested in the Tudor dynasty and the many uses of plants. He grew up learning about plants from his grandmother Anne Kelley and mother Diane Prickett. Their love of plants has manifested in Seamus through his love of being out in the wild looking for medicinal plants, through his spending lots of time in the family garden and through spending time in the woods in the Pacific Northwest. He is most often seen with his head down, looking at the plants along the path and not at what lies ahead.

Seamus O’Caellaigh has always been interested in the Tudor dynasty and the many uses of plants. He grew up learning about plants from his grandmother Anne Kelley and mother Diane Prickett. Their love of plants has manifested in Seamus through his love of being out in the wild looking for medicinal plants, through his spending lots of time in the family garden and through spending time in the woods in the Pacific Northwest. He is most often seen with his head down, looking at the plants along the path and not at what lies ahead.

Having joined a pre-1600s recreation group, Seamus found a way to incorporate his love of the Tudors with a study of medicinal plants from that time period, along with the many herbal books written from the 1st century to the turn of the 17th century. Nothing makes Seamus happier than finding an obscure reference, or his son Jerrick bringing him a plant for “Dad’s Plant Projects.”

Seamus’s book tour has also included these blogs:

Notes and Sources

- Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 14 Part 2, 153.

- “Ordinances for the household made at Eltham in the XVIIth year of King Henry VIII A.D. 1526”, 174 in Nichols’ A collection of ordinances and regulations for the government of the royal household, made in divers reigns. From King Edward III. to King William and Queen Mary….

- Dioscorides de materia medica: being an herbal with many other medicinal materials., Book 2, 263.

- Schilling, Judith A., and Sean Webb. Nursing Herbal Medicine Handbook. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2006.

- Malik, Enas M., and Muller, Christa E., “Anthraquinones As Pharmacological Tools and Drugs”, Medicinal Research Reviews 36.4 (2016): 705-48. Web. 18 Jan. 2017.

From other things I’ve read the lower classes ate far more healthy fare than those higher up. I know from the research done on the remains of Richard III he had consumed things that may not have tasted very good because they were hard to aquire (peacock). I’m sure at Henry’s table, he being so caught up in his own majesty had some pretty exotic and not so healthy things served to him during his reign.

Yes, the wealthier classes could afford meat and showed off by consuming lots of it, whereas the lower classes ate more vegetables and would survive on pottage with different vegetables added according to what was in season and what they could get hold of.

The Tudor Monarchs and nobility ate huge amounts of meat it’s true, swans and yes peacocks, all served and dressed in their natural state to take pride of place on the table, joints of beef pheasants partridges, quails and chickens made in huge pies decorated with figures on the top, many types of fish sturgeon pike etc, and then wonderful desserts made with marzipan, marchpane as it was called then, gilded with rose water, dishes piled high with fresh and dried candied fruit, Henry 111 and Anne Boleyn particularly loved cherries and they had several orchards, imagine the wonderful fare at the banquets, silver tankards filled with wine and winking in the candlelight, the colourful array of the sumptuous dishes spread along the huge refectory tables, the company dressed in their colourful outfits and the sound of the musicians in the background, chatter and laughter and music, the great hall at Hampton court or Greenwich or Richmond, dazzling with tapestries and the overworked pages scuttling to and fro, the rich are well and Henry as we know ate more than most but they had little knowledge of the need for fibre which is what the body needs to produce soft stools, constipation as we all know for we have all suffered from it at some time in our lives is caused by luck of fruit and veg, nowadays manufacturers add fibre to ready meals and there are more they say in breakfast cereals, but bran is the best cereal to have, I hate it and prefer porridge, we know the need for fibre but there are people today who just live on takeaways and donuts and are not earning hardly any fruit or veg, as Michael says the poor in Tudor times ate little of the latter, vegetables was ate by the poor as it was cheap and easy to grow, therefore the farmer and his wife must have spent a quarter of the time on their toilet than poor Henry did, he did consume large amounts of wine to with sugar and it is believed he suffered from and possibly died from type 2 diabetes, imagine if chocolate had been around then I reckon Henry would have been twice the size he eventually became, and been more constipated, Seamus’s book does sound very entertaining and well researched.

I just can’t get over the fact that this one king had health problems plentiful enough to fill whole books! It’s a good thing such meticulous records were kept and still survive. I’m sure they have benefitted in the education of doctors past and present. I can’t help but smirk and wonder how His Majesty would feel knowing that 500 years after his reign, these are the great things that are remembered about him! LOL!

Agreed. During his reign we all would probably be convicted of treason and have our heads removed for ‘impugning the king’s dignity’. Sure glad we live in the 21st century because as odd and somewhat gross as this topic is, it is entertaining.

I am not surprised they had bowel problems. Have you ever eaten meat for a few days on the run, red meat rather than white and had a few drinks and partied? You soon need to modify your diet with veg or salads, including nuts and more fibre. It was the weird stuff they ate. And they probably ate more than the average person as well. I am surprised, however, that they didn’t use senna as it has been around for thousands of years and known to relieve constipation. On the other hand an enema was something quacks recommended so it is not unexpected Henry would follow that advice. Whatever he did, obviously worked as the closed stool had a goodly siege at 2 a.m. Pooh!!!

I would just like to add, with Steve we have to follow the opposite advice as high fibre and fruit and vegetables are not good with a stoma. You need low fibre, oat fibre and anything which thickens and starch and pasta are particularly good. As a pie man, he has no problem with this. What’s in and what’s out is a real hit and miss affair at first, but you soon get into a routine. Chicken is also much better than red meat and we both like that. White bread is in, but good bread, you know wholemeal, is out, save for me, which makes shopping really odd. Bowel health is so important today, it’s no wonder some people actually died from food problems back then.

Human beings by origin are vegetarians not meat eaters, hence our small teeth, we have not the carnivorous teeth that cats and dogs have, to eat a diet made up mostly of red meat is not good for the human body, we need iron which red meat has but then eggs and cheese and strawberries to contain iron, in fact there’s supposed to be more iron in strawberries than a juicy steak, there’s also fibre in brown bread, wholemeal and granary and sourdough, not white bread with brown added, (the cheap variety) and white meat has been known for some time to be far more superior than red meat, both pork and lamb are fatty meat and I dread to think what Henry’s cholesterol level was like, he ate huge quantities of meat and in pies to, thickly covered in pastry, in Weir’s book ‘Henry V111 King and Court’, she mentions he was fond of fruit and ate plenty but obviously it wasn’t enough to improve his bowel movements, imagine being his doctors and having to examine his stools! Urgh.

Y coin Weirs book Henry V111 King and court she mentions that Henry was very fond of fruit but

Made a mistake there sorry!

We are omnivores. Our teeth and digestive systems are designed for eating both meat and vegetable matter. We have incisors in front for tearing flesh and molars for crushing and breaking down plant material. People who are strictly vegetarian also have problems; namely anemia. Iron supplements will help with this. We as humans need both kinds of food. Personally I would love to eat only meat but I do not want to end up like the King.

I’m a vegetarian with vegan leanings and I don’t have any problems at all with any deficiencies. I’ve never been anaemic or needed iron supplements. Iron isn’t just in red meat, it’s in pulses and beans, nuts and seeds, dried fruit, dark green leady veg, wholegrains, tofu, all sorts. People are always telling me that a vegan diet doesn’t give you enough protein, but that’s a myth as protein is found in lots of non-dairy milk, nuts and nut butter, lentils, veg like spinach and kale, seeds, quinoa, tofu, beans etc. Meat and dairy don’t suit my digestive system, so I gave up meat and have cut down on dairy. All my levels in a recent blood test were super healthy.

I just reread what I wrote. I apologise for sounding so insulting. That was certainly not my intent. The only experience I have with vegetarianism is my wife and her sister. Neither fared well. My wife ended up in the hospital for a week with severe anemia. This was 30 yrs ago. Please continue to stay healthy. We all need you.

Don’t worry, I wasn’t offended. If people just cut things out of their diet without making sure that they’re replacing key nutrients then they will be unwell, it’s all about having a healthy and balanced diet, whether that includes meat or not. Regarding anaemia and iron, there are so many ways to get it other than meat but you have to make sure you eat those things.

Thank you!

May I ask what is quinoa and tofu? I love kale and spinach, especially as part of a mixed salad with fruit and nuts and chicken and herbs. I have not heard of the others.

Thanks.

Quinoa is a grain, a bit like cous cous, and it can be used like rice or pasta. You can do quinoa salads, put it in casseroles and stews, all sorts. Tofu is used a lot in Asia and is bean curd. It’s a great meat substitute as firm tofu can be cut into chunks and then cooked in sauces like you would with chicken pieces. You can also marinate it. Soft tofu can be used in dessert recipes.

I eat a much more varied diet now I’m veggie and I’ve discovered all sorts of beans, pulses and sees that I’d never tried before. I love a spinach/kale, mango, banana and seed smoothie! I bought a nutri-bullet and I smoothie everything!

I also run three times a week and walk so try to keep healthy. Tim and the kids still eat meat but Tim now east a lot more veg as he’s sharing my veggies recipes too.

Thanks, Claire, I prefer salads to most other things with meals so I am very creative about what goes into them, have always mixed in fruit and nuts and it is amazing how creative you can be. I am allergic to tomato so that’s out, but the more colourful the better. I think I will try quineo, it sounds very nice. Thanks again.

Yes I stand corrected, omnivores that’s right Michael, personally I love meat but don’t eat a lot of it, I may have lamb or beef once a week, Henry’s problem was he had always eaten heartily but in his youth he had been very athletic, however he continued to eat like that when he became less mobile thus the extra weight, quite possibly the depression he must have suffered from at the problems in his legs, his marital affairs etc made him over eat also, just seen your post Claire your diet just be very healthy, what do you eat at Christmas though, do you cook a bird?

The rest of my family are meat-eaters so I do roast dinners for them, and the usual Christmas dinner, and I just replace the meat with something veggie like a nut roast, mushrooms in a sauce or a slice of veggie lasagne. I do a suet free Christmas pud too.

Sounds delicious I like veggie food as well as meat it must be good for your cholesterol to.

I had bloods taken two weeks ago and my cholesterol levels were very healthy, whereas they’d been borderline when I had them taken the last time, when I was eating meat and more dairy foods.

I went veggie because Tim and I did a ten day “fast” which was ten days of avoiding meat, dairy, alcohol, processed foods etc. and instead eating salads, plant-based meals, veggies soups, fruit and veg smoothies etc. and I felt so much better. I have suffered with IBS since I was 19 and it really helped, so I decided to keep off meat and lower my dairy intake. I discovered beetroot and orange juice – yum! Also apple and ginger! So many things I try now that I didn’t before.

Its not about being vegetarian or not but making certain you have as balanced a diet as possible, because we can’t just eat meat or fruit and vegetables. Some very young vegetarians don’t supplement their meals, which is why they are deficient as they don’t eat pasta, eggs, cheese, pulses, a wide variety of fruits, potatoes, breads and nuts or vary their diet enough. The same can be said of meat eaters who don’t touch vegetables, don’t have salads of any description, pulses, potatoes or even fruit. If we eat too much of the wrong stuff or even too much of the right stuff we are going to be missing some vit or other as there are dozens that we need, not just the obvious ones. It’s all about DASH which is a diet that stops you getting high blood pressure and is a very well balanced one for modern lives. You eat something from each food group regularly four times a day and it gives you lots of energy. Exercise is also important, any exercise, gardening is good as is walking, within your capabilities, which is why Henry probably didn’t have too many problems when he was active as he would have worked it all off, but as he put on weight it must have been difficult. It really doesn’t matter, however, if we are vegetarian or eat meat and fish, because we all forget to eat properly and eat what tastes nice, usually a great big cream cake or ice bun, with fish and chips or a pasty or something else, but we don’t always follow the advice on a mixture of five a day and varied diet. We eat as we feel, because we eat what we enjoy. As long as we try to balance it out over time, personally I would rather due happy than eat so plainly I was miserable. On a DASH diet there is a lot of variety and taste and it is very enjoyable. I think that is the key, enjoying food and variety. Just don’t pig out on too much fatty stuff, have a piece of fruit occasionally. By the way, contrary to popular myth, a cooked breakfast is not bad for you. If you swap the sausage for homemade and grill or bake the bacon and poach the eggs, with mushrooms you are actually getting a very balanced, plenty of fibre and good carbs. If you add tomatoes, have them fresh and this is one of your five a day. Baked beans today also come in a sauce with far less fat and salt and more taste. Steve actually has to have a lot more salt in his diet than the average person because he can’t absorb food otherwise, thus he gets dehydrated quicker as he only has part of his colon. To make certain he eats a more varied diet he eats pasta and rice and any fruit has to be really cut up and skinned. By drinking fresh full juices that help his system he gets enough B12_which is an essential vit for absorption. So pomegranate juice or apple and cranberry are good super fruits as is blueberry juice and apple, pear and mango, combined are all rich in the right supplements without taking too many extra things. He has to make certain he doesn’t eat too many pies, though as obviously this would put on too much weight. It’s a balancing act but of course today we have access to so many different things and you don’t have to be wealthy to eat most of them. What makes me laugh about the Tudor elite was they did have a wide variety of fruits from the new world and home grown ones and they had fresh produce but only for a short seaon, but in any event they failed to serve it as often as they should. Their diet was heavy on fish and meat but they also served some very odd, rich things like porcupine, dolphin, pheasant, sharks, even swans and peacocks. If they could get hold of them lizards also ended up on the menus, but it was mostly boar, pigs, venison, beef and the Tudor sweet tooth is very well known, making sculptures out of icing and sugar and marchpane. They spared no expense and a meal lasted a good couple of hours. They ate pies, but not the pastry as it was designed to preserve, not to be eaten, but the contents were very rich, birds being a favourite. They had some weird thing called a coccatriece which was two animal halves sown together and served, so it might be half salmon, half peacock for one example. They used exotic herbs and rich sauces and several courses were served. Now they didn’t eat very large amounts of food, all piled up, this was a time to entertain and you selected from a variety of dishes and only ate what you could eat. Henry Viii was a large man so he probably did eat well, but his main problem was later in life when he also comfort ate, had far less exercise and so his weight ballooned. In his healthier years he could pick up malaria and shake it off, but it returns every few years as it does now, but when he was more static, he developed long term health problems that come with obesity of his excessive size and he couldn’t do anything about them. Henry may have had anything from Type 2 diabetes to blocked arteries. We don’t know for certain if he did, but it’s a reasonable assumption that he had some of the conditions associated with extreme weight gain and a rich diet. Any combination would kill him prematurely.

BQ, how is Steve doing now?

Steve is generally doing fine and he has most of his diet under control, although I have to remind him if something has caused chaos before, as he forgets. He is hoping for reversing the stoma in the Summer or Autumn, but he has to have radium therapy first, as he had prostate cancer in 2009/10 and although everything was fine, they have found a tiny nubbin which can mean a possible fatty lump or tiny spot of cancer, more the former but they have to be certain so he has had injections and two upcoming sessions in April. He has mostly good health so his reverse and hernia repair should go well. We have the best surgeon in the country, with an international reputation, so he is very confident of a big success and looking forward to it. He doesn’t have the confidence to do certain things of an evening now in case his bag gets active, so I booked a few things starting at different times, for both of us and after it behaved perfectly, now he is fine. I keep telling him it will behave better out of the house and I am correct. It is better behaved when we are on holiday so it was obviously going to behave if we go out. It’s not as if places don’t have accessible loos these days. The first time we went away as a couple was a nervous time a year afterwards, but he was fine. His stoma nurse told me to make sure he had his tablets and supplies but make him do as much himself as possible. Oh and don’t walk back with him if we are out and he has to go back to find a loo, he has to gain confidence himself. We were actually somewhere we knew so it was fine. He is much his old self now so I don’t have to worry about him.

Thanks for asking, Claire, we both appreciate it. The loo really is the human topic we all share. hahaha.

so clare u have IBS? so do I along with other stomach issues maybe I should try cutting meat an dairy out too! I could deal with out meat but I don’t know about dairy I love cheese!!! dose it really help your stomach issues? thanks!!!!

It just depends on what affects your digestive system. I felt better cutting them out but that’s just my body. You could try cutting meat our for ten days or so and see how you feel. It’s so hard to know what causes it, isn’t it?

Hi Carrie, a friend of mine and my nephew has IBS and they both found cutting out fatty foods like cream and cheese helps, also certain veg like sprouts can cause problems and my nephew can’t touch sweet corn or granary bread, also fizzy drinks cause problems to but I think it’s all down to the individual, you just have to see what foods cause you problems and eliminate them one by one from your diet, pain I know, good luck!.