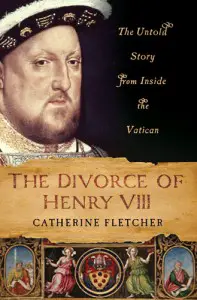

Thank you so much to Catherine Fletcher, historian and author of “The Divorce of Henry VIII: The Untold Story from Inside the Vatican”, for this guest article. You can read my review of Catherine’s book over on our review site – click here.

Thank you so much to Catherine Fletcher, historian and author of “The Divorce of Henry VIII: The Untold Story from Inside the Vatican”, for this guest article. You can read my review of Catherine’s book over on our review site – click here.

Over to Catherine…

In the six years it took Henry to end his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, dozens of people were employed in the ‘divorce’ negotiations. Who were the key players, and what do we know about their relationships with Anne?

Henry did not initially plan to break with Rome. In 1527, as he first began working towards marrying Anne, he and his advisers hoped to persuade Pope Clement VII to agree that Henry’s marriage to Catherine had never been valid. It took almost three years of serious negotiating – and another three of delaying tactics – before the final rift came. Against the backdrop of a disastrous war on the Italian peninsula, Henry dispatched a series of envoys to the papal court. But they struggled to persuade Clement, a member of the Medici family, whose priority was getting his exiled family back into power in Florence.

Henry entrusted the first negotiations with Pope Clement VII to his secretary, Dr William Knight, an experienced diplomat. But when Knight arrived in Rome he found it virtually impossible to see the Pope, who was under siege by the troops of Charles V, Catherine of Aragon’s nephew.

After Knight failed to get the commissions required, Cardinal Wolsey managed to take control of matters. (As Jessica Sharkey’s intriguing research shows, Wolsey had been sidelined during the Knight mission: http://eastanglia.academia.edu/JessicaSharkey.) Wolsey issued new instructions to Henry’s permanent representative in Rome, the Italian Gregorio Casali. Casali had entered the English service some eight years earlier and had been accredited as ambassador to Rome in September 1525. He was joined at the papal court in March 1528 by Stephen Gardiner and Edward Fox, two up-and-coming Cambridge-educated lawyers.

Only in 1529 did anyone close to Anne Boleyn get involved in the diplomacy. That was Sir Francis Bryan, her cousin (their mothers were half-sisters). Sir Francis, one of Henry’s inner circle, was nicknamed the “Vicar of Hell” for his raucous behaviour at court. He was even alleged to have slept with a courtesan in Rome in an effort to gain information useful to the king’s cause. While on mission to Rome he corresponded directly with Anne, the only one of the diplomats we know to have done so.

As it became clear to Sir Francis that there was little hope of a negotiated settlement, he was reluctant to disclose the bad news to Anne. He wrote to Henry: “I dare not write unto my cousin Anne the truth of this matter, because I do not know Your Grace’s pleasure whether I shall so do or no; wherefore, if she be angry with me, I most humbly desire Your Grace to make mine excuse.”

There was more trouble for Anne at the end of 1529, when Sir Nicholas Carew headed to Italy as a special envoy prior to the coronation of Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor. (Anne’s father led an embassy to Charles too, shortly afterwards, but did not get a warm reception.) Sir Nicholas, one of Henry’s leading courtiers, was married to Elizabeth Bryan, Sir Francis’ sister, but he and his wife were friendly to Catherine and Princess Mary. Later, in the mid-1530s, they threw their lot in with the Seymours: Henry and Jane met a number of times at Carew’s home, Beddington.

Little is known about the detail of Carew’s mission, but it was alleged that some of the king’s envoys in Bologna behaved disloyally, encouraging their colleagues ‘to hinder and trouble these the king’s causes’. Was Carew among them? The Spanish ambassador in London, Eustace Chapuys, certainly claimed that he favoured Catherine. Chapuys’ counterparts in Italy were keen to pick up on any hostility to Anne. They reported that both William Benet, another English diplomat in Rome, and Giambattista Casali (Gregorio’s brother, who acted as English agent in Venice) had expressed worries about Henry’s plans.

Anne herself found occasion to castigate Gregorio Casali for his failures when the pair met in October 1532. A report, albeit at second- or third-hand, recounts that she ‘ill-treated’ him ‘for not managing her affair better, for she had hoped to be married in the middle of September’. As the one man present in Rome throughout the years of negotiations, he was an obvious target for her wrath.

The Spanish, however, struggled to find firm allies among the English diplomats at the papal court. For the most part they seemed to respect Henry’s orders, whatever their personal views. Chapuys had more luck with courtiers back in London, including Elizabeth Howard, wife of Anne Boleyn’s uncle. On one occasion she smuggled a copy of one of Casali’s letters to Catherine, concealed in a gift of ‘poultry and an orange’. Anne did not need to look to Rome for enemies: she had plenty back in London.