December 15: Knight's Fork

Thank you to historical novelist Loretta Goldberg, author of the Elizabethan spy novel The Reversible Mask, for today's contribution, which is from her work in progress which has the working title Knight’s Fork: An Elizabethan Spy Novel of Sir Edward Latham and is a sequel to The Reversible Mask. The scene features a manuscript which really does exist and you'll find details about it after Loretta's excerpt.

Scene from Knight's Fork: An Elizabethan Spy Novel of Sir Edward Latham

A SURFEIT OF ENEMIES

Wimille, Franc., 12 December 1589 Gregorian Calendar; 2 December 1589 Julian Calendar in England.

After two days of watching the Wimille house, Edward Latham decided it was safe to knock on the back door. Dame Fortune’s favours to me must be near emptied, he thought. Too many espials for Elizabeth; too many foes. Still, this place looks secure.

Sir Francis Walsingham had bought the house, badly damaged when Henry VIII sacked Wimille in 1544. The spymaster used it as a derelict but safe place for his agents to meet. Latham’s handler and former court friend, David Hicks, had arrived from London yesterday. In disguise, snow-spattered and shivering in a biting east wind, Latham had stood vigil overnight. He’d detected no threat.

Now, as the bells of squat St. Pierre Church tolled eight a.m., Latham presented himself at the servants’ entrance. He was dressed as a gypsy woman in threadbare skirts. His blond hair was a matted dyed brown, strands poking from a wool cap over a faded blue kerchief concealing his broad shoulders.

“Rodomontade!” (braggart) he called through the closed door. Swapping insults in the language of the country where they met was their password.

“Hircine avec lientery embouche!” (smelly goat with diarrheal mouth) Hicks parried. Hicks opened the door, wearing a workmanlike sword at his waist. He beckoned Latham in.

Latham followed him to the main room, noting a sheathed knife between Hicks’s shoulder blades. Hicks had spread a blanket on the pitted wooden floor. A flagon of small beer and two tankards stood on the blanket, along with a platter of bread and cheese. His cropped hair’s gray, Latham mused. That silver-hoop earring glints over tired green eyes. and I bet that sag on his cheek means he’s given up a molar to the tooth drawer. The years tread all of us. Latham took off his cap and scarf, revealing two knives and an illegal wheel lock pistol.

“David,” he burst out as soon as he was comfortably seated, “why does Elizabeth insist that England keeps the old Julian calendar, ten days behind the rest of Europe, which uses Gregory’s dates? I’m meeting you on Tuesday while you’re meeting me last Saturday. It’s confusing.”

“Come on, Edward. You know the answer. The name Gregory is anathema. That Bishop of Rome and his successor tried to assassinate Her Majesty and destroy our realm. Still try.”

“Yes, yes. But after defeating the Spanish armada last year, surely Elizabeth has nothing to prove.” Latham stopped at Hicks’s bored stare. Scratching his hair, he continued, “Adamant, I see. Dye’s a torment. I don’t know how many more missions my luck can compass. I need to come home. I have an astonishing document that will secure my reputation.”

Hicks sighed. “Edward, you left England twenty years ago and served Catholic monarchs abroad before devoting your talents to helping us. Your value to Her Majesty is your foreign contacts.”

Latham frowned. Give him time. He pivoted to his last dispatch. “What did Her Majesty think of my espial, the convoy of Hansa merchant ships carrying war materials to resupply Spain?”

“Giving us the sailing date and unique route designed to evade us was excellent. As you know, ‘El Draco’ captured all sixty ships and brought them back to Plymouth, with their cargoes. The Admiralty Court has it all for adjudication. Her Majesty gave the Hanseatic League fair warning. They didn’t listen. Humbling these arrogant traders getting rich off both warring sides will help us, in time. But we have so many problems no one has the belly for cheer. We drum our fingers, dreading the next Spanish armada. Hopefully, taking these war supplies will delay it. What’s the document?”

“David, know that my enemies are increasing. Apart from suspicious Spanish intelligencers, there are holdover Huguenot thugs who’ve never learned that I’m now Elizabeth’s best man abroad, and of course it’s too dangerous to tell them. In addition, a Hansa merchant hired a factor who stays close to me and my manservant. It’s getting crowded! Happily, these foes don’t love each other.” He crossed himself. “God’s will be done. Well, the document.”

As Latham drew a thick sheaf of papers from his basket, he felt the familiar tingle from toes to scalp that accompanied his passing on of materially significant information.

“I took it from an Italian printer’s shop one late Saturday night. In a fever, I copied the Italian and returned the papers before dawn Monday. Undetected. I rode post here and translated it. Under colour of being ambassador to Sultan Murad III in Constantinople, this Catholic spy has analysed the Great Turk’s Empire: twenty-five pages detailing armed forces, money, religion, form of government, social conditions. Elizabeth has worked for years to build a Turkish alliance, and Murad has become friendly…”

Latham paused. He and Hicks exchanged grins while Latham nibbled a bread crust. Latham gave himself a moment to relish the memory of discovering, in a Constantinople warehouse owned by Murad and bypassing customs inspection, Elizabeth’s secret gift of silver, brass and gold artifacts from Catholic monasteries and churches for Murad to melt down for his needs. A gift that Elizabeth had kept from her Privy Council.

“The Ottomans don’t like Spain any more than we do,” Hicks agreed. “We need Murad’s goodwill as we continue to fight Spain.” He began to whistle as he flicked through the pages.

Latham grabbed his arm. “Read it sceptically, David. It has subtle policy. By craftily exaggerating the Great Turk’s weakness, it makes war against them seem profitable. This writing can help Her Majesty and Murad, and me. It’s a knight’s fork of a document.”

“Our Turkey Company is doing well since Murad granted us exclusive trade preferences,” Hicks mused. “War in Ottoman lands is against our interests. Go on.”

“Because of my time in Constantinople I can ferret out the writer’s purpose and flaws. Murad will appreciate Elizabeth sending him the document. His Grand Vizier will know, by the manner of complaints recounted, what factions bent the spy’s ears. I excerpted key points.”

Latham read aloud: “‘I intend not to declare in what voluptuous vice and delights the Turks nowadays are wrapped in …’”

Hicks pumped his own thigh with a fist. “I see this man mislikes the Turk!”

“Not subtle,” Latham laughed. “‘…only this must I say that as heretofore there did covet nothing more than wars, weapons, and motion…’ This is a complaint of a particular faction,” Latham explained. “Listen. ‘Now contrarywise the chiefest of them yea and the rest after the example do highly abhor the same in such sort as when any enterprise is in hand, many of them did make great presents and bribes to avoid both the danger and the charge...’”

“Aha. Corruption. How strong is this faction?” Hicks asked.

“Not strong. They’re dispersed Turk warriors yearning to be heroes like our Arthurian knights. They have chroniclers and dervish leaders they follow. The ancestors of these warriors enlarged Ottoman lands last century. They were paid in land their descendants must manage. The land isn’t rich. Listen. ‘themselves confess that although their Empire be great and of so many Kingdoms, yet a great part thereof is weak, disinhibited and ruined being among the Turks, an ordinary proverb, that in what soil soever the Ottomans’ horse do feed, never after there growth any grass.’ For his security, David, Murad keeps an army ready in peace and war paid by salary. This spy estimates it at one hundred and thirty thousand. European Princes don’t have that.”

Hicks whistled again.

“Put your arms around the essential point,” Latham continued, reading on. “’That monarch is not so well fortified as were necessary to resist a war,…by how much their people subject to them are their connived enemies, and chiefly in those countries that do not only confine with Christian princes, but besides this are inhabited with people, although not Christian, yet their foes, being those Turks of the Persian law…There is also great hatred, and emulation, between the Great Turk and the King of Persia. The opinion of this Ali (founder of Persian Islamic law) is not only holden through all the Persian Empire, but also it is favoured through all the provinces of Asia, although such as are the Turk’s subjects, and namely those about the gate…’ The writer refers to the royal palace and central administration as the ‘gate.’ ‘do keep the same secret…’”

“Seething near-complete hatred?” Hicks asked.

“Much exaggerated. There aren’t hordes of Sufis running the ‘gate’ waiting for deliverance by the Persians. My great friend, Ahmet Gul, a tax collector there, keeps me informed.

“Here’s his true aim. ‘The Persian is very superstitious, yet valiant, and very warlike, and, therefore, were it not amiss that the Christian princes should make account of the Sufi and to have straight intelligence with him to the end to dispose of his forces …with artillery and other weapons for the war against the Great Turk, and to restrain the Turkish insolence, the intelligence of Christian princes with the Sufi were doubted a very good bridle….’”

Hicks ate and drank while he absorbed what he’d heard. “Obviously, the spy means Catholic when he writes of Christian princes. He’s exhorting Catholic princes, who don’t have the forces to attack the Ottoman army directly, to fight to the last Persian life, giving them artillery and other weapons, it suggests? All the while leaving Spain’s navy free to concentrate on us. Ha, ha! A juicy strategy, indeed. Well done, Edward. So, it’s being published to rally these Catholic princes. Sir Francis will like this espial.”

“Here’s the Italian original and my translation. Her Majesty will want to check my accuracy!”

Hicks laughed. “Our careful Queen will do that. I’ll try to get you traveling papers home.”

A few hours later, the two men left the house, Latham now wearing the livery of Hicks’s servants. They rode in silence toward Calais. Every so often Hicks patted his saddlebag containing the Constantinople paper.

Finally, Hicks turned to Latham, looking embarrassed. “Edward, I’ll plead for your immediate return, urge using a different man for the next job. But I must warn you, you may be asked to go to Spain again. One of our reliable men is silent. We must learn what happened, for the safety of several others.”

Fear slammed Latham’s gut and diaphragm. For a moment he was cold and breathless with fury. But the irresistible thrill of a challenge soon loosened his muscles. He was two men: a seasoned diplomat/spy calculating likely outcomes; the twenty-three-year-old idealist who’d chanced everything on adventuring into an uncertain future. He gulped in dank bracing sea air. God’s will be done.

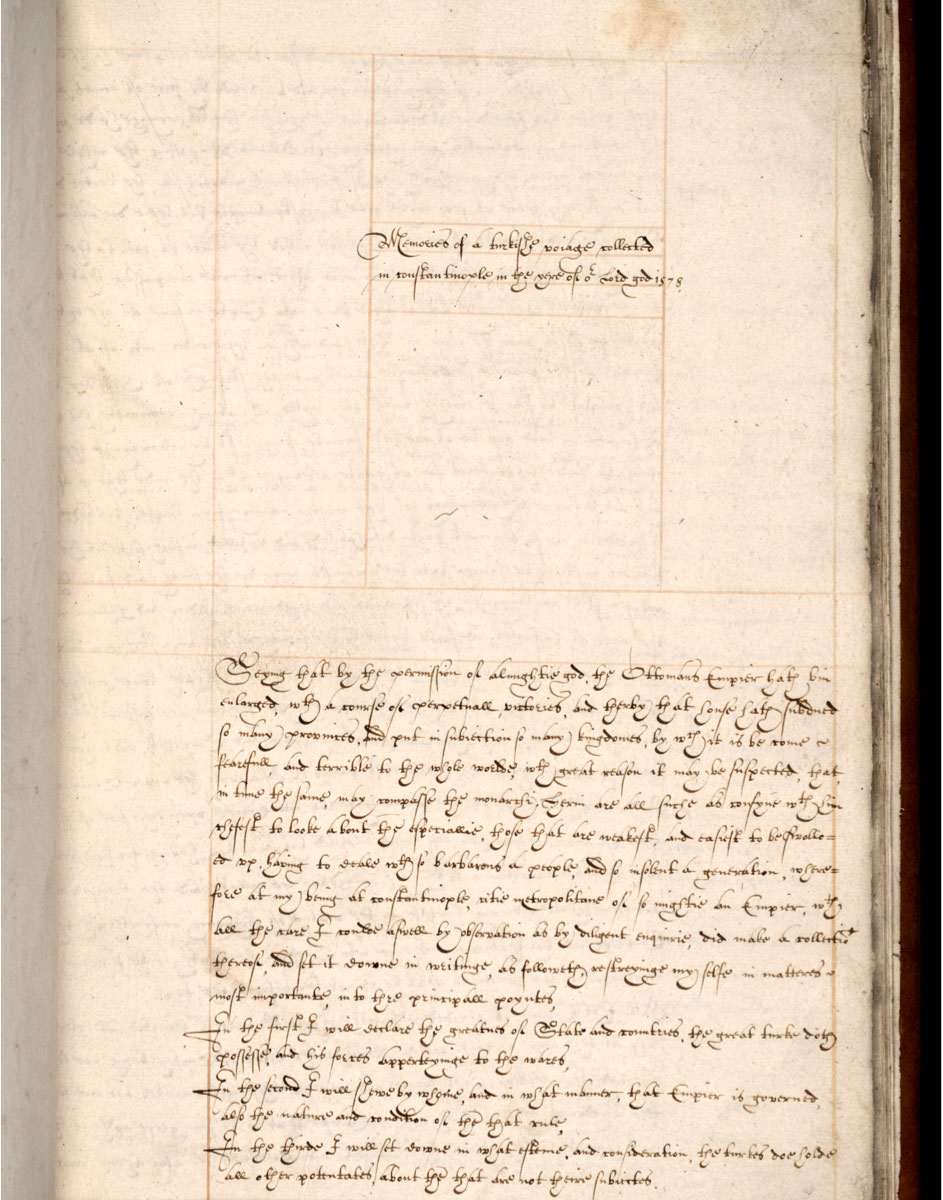

This extraordinary single-spaced twenty-five-page document is in the Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscripts Library at Yale University: Relation of Sir Anthony Standen. Memories of a Turkish Voyage, collected in Constantinople in the year of our Lord God 1578. My transcription is by Jacqueline Lye.

Scholars Kathleen Lea, Geoffrey Ashe and Leo Hicks attribute the document to Standen, taking his name on the title page at face value. However, the style is inconsistent with Standen’s confirmed dispatches contained in the papers of his handlers, Anthony and Sir Francis Bacon. A fourth scholar, Susan A. Skilliter, suggests that Standen translated from Italian the work of Venetian envoy Marchantonio Barbaro and put his own name to it. This makes much more sense historically. In my novel, my anti-hero, Sir Edward Latham, loosely inspired by Standen, claims only translation credits. That contribution to his country’s security is already enough.