December 9: Palace of Sheen/Palace of Richmond, Surrey

Thank you to author Kristie Dean for sharing this excerpt from her book ‘On the Trail of the Yorks’ about the fire at Sheen.

As with Greenwich, Elizabeth [of York] would know two palaces here – the palace of her youth, known as Sheen, and the palace built by her husband, known as Richmond. The palace of Sheen had been visited often by royalty over the years, with Edward III dying here. Richard II especially loved Sheen, and he and his wife, Anne, visited here often. Following Anne’s death, Richard II order the building demolished. Under Henry V and Henry VI, building commenced on another palace nearby.

The palace of Elizabeth’s youth was built on a grand scale using freestone, beer stone, timber, ragstone and brick. Two large stone towers were on the east side of the palace adjoining the timber building known as Byfleet. A large brick wall enclosed a garden. The History of the King’s Works describes the construction:

a ‘great moat’ 25 feet wide and 8 feet deep…being dug between the old site (veterem fundamentum) of the manor of Sheen and ‘the new building of the manor of Sheen’, and a palisade was being erected ‘outside the moat of the manor of Byfleet joined to the new building of the manor of Sheen’… a new range of chambers was under construction on the north side…

The rooms of the castle were filled with stained glass containing the king’s arms and other devices. William Worcester said the castle also contained a large courtyard surrounded by chambers. Elizabeth would have visited here several times during her father’s reign.

Following their marriage, Elizabeth and Henry often stayed at Sheen, often celebrating Christmas here. During the Christmas celebration in 1497, on ‘St Thomas day at night in the Christmas week about nine of the clock’, a great fire broke out within the king’s or queen’s lodgings and lasted several hours. The damage from the fire was extensive, but, even though several members of the royal family were lodged here, no one was hurt. The Milanese ambassador, de Soncino, reported the incident:

Fire broke out in the palace where his Majesty was staying with the queen and all the Court, by accident and not by malice, catching a beam, about the ninth hour of the night. It did a great deal of harm and burned the chapel except two large towers recently erected by his Majesty. The damage is estimated at over 60,000 ducats. The king does not attach much importance to the loss by this fire, seeing that it was not due to malice. He proposes to rebuild the chapel all in stone and much finer than before.

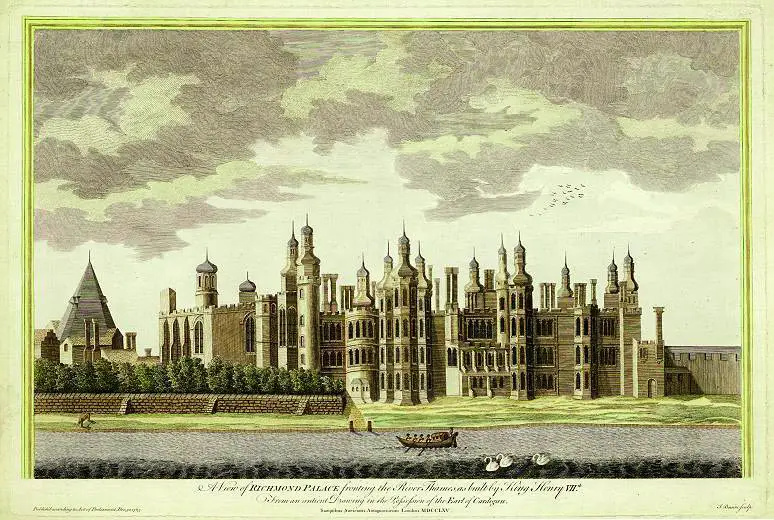

Henry V’s donjon was not destroyed, although its interior seems to have been devastated. Henry VII began a rebuilding project and by November 1501 had finished most of the new works, which became known as Richmond. The privy block which contained Elizabeth’s chambers were three storeys high and built of white stone. Her chambers had large bay windows which looked out over the Thames. The palace towers had turrets with pepper pot domes, each topped with a vane of the king’s arms, painted and gilded. It was encircled with a strong brick wall with towers of different heights standing in each corner and in the middle. The Southwest London Archaeology Unit believes that Henry’s palace was also moated and built on the same ground plan as Sheen. The king and queen’s chambers were reached by a bridge over the moat from the courtyard.

Entrance to the palace was through its strong gates of double timber. Visitors entering through the inner gateway saw a large courtyard, with galleries surrounding it on each side. These galleries were well lit by many windows and led off to the chambers for courtiers.

On 25 January 1502, Elizabeth’s daughter, Margaret married the king of Scotland in a proxy ceremony at Richmond, giving Henry a chance to display its ‘great comodities, pleasures, and excellent goodlynes’ to his Scottish guests.

As the morning of her daughter’s wedding dawned, Elizabeth made her way along the paved and painted gallery to her privy closet in the chapel to observe Mass. Henry’s closet was cushioned and hung with silk, and his altar was plated with relics of gold and precious stones. Elizabeth’s closet, located on the right hand side of the chapel, was similar to her husband’s. The chapel itself was ‘well paved, glasid, and hangyd w‘ cloth of Arres’. The ceiling was white washed and painted in azure, having ‘between evry chek a red rose of gold or portcullis’. Each wall contained statues of past kings who had become saints, like St Edward and St Edmund. The choir and nave were hung with cloth of gold. After Mass, Henry, Elizabeth and many others made their way to the Queen’s Great Chamber for the ceremony.

After the questioning part of the ceremony concluded, the Archbishop of Glasgow turned to Margaret and asked if she was entering the marriage of her own free will and without compulsion. Margaret answered that if ‘it please my Lord and Father the King, and my Lady my mother the Queen’. Margaret then received the blessings of the king and queen before the Archbishop secured the promises of King James from the Earl of Bothwell.

Margaret then spoke her vows, taking the ‘said James King of Scotland unto and for my Husband and Spouse, and all other for him forsake, during his and mine Lives naturall…’ Afterwards, the trumpeters blew and the minstrels played. Elizabeth then took Margaret by the hand and they dined together.

The next day a great tournament was held in honour of Margaret’s marriage. Afterwards a large banquet was held in the Great Hall, which sat across the Fountain Court from the chapel. The court was paved with free stone, and in the middle of its courtyard stood a large conduit and cistern, decorated with lions, red dragons and other beasts.

As the visitors crossed the courtyard and entered the hall, they would have walked over the tile floor to stand under its timber roof with its ‘knotts craftily corven, joined, and shett toguyders with mortes, and pynned, hangyng pendaunts’. The hall was built of stone and was about one hundred feet long. Its walls were decorated by rich tapestries of arras depicting scenes such as the siege of Troy. Statues of former and mythical kings in gold robes and swords in their hands were placed between each of the large windows. A statue of Henry VII was slightly higher up on the left-hand side of the hall, since he was ‘as worthy that room and place with those glorious princes as any King that ever reigned in this land’

The palace of Richmond also contained gardens, which abutted the chambers on the east side. The gardens were large, containing herbs, flowers and decorative stone statues of beasts. A two-storey gallery encircled the gardens, with the upper floor enclosed so that courtiers could walk around and admire the gardens. On the far side of the gardens was an area where visitors could play chess, dice, cards, bowl, or play tennis.

Elizabeth would spend her last Christmas at Richmond. Having lost her oldest son, it was likely a sad Christmas for both her and her family.

Kristie Dean has been published widely in magazines and newspapers, as well as being involved in the International Congress on Medieval Studies. After completing her MA in History with high honours she began to teach and was the recipient of the Outstanding Teacher of the Year award for her district. She lives in Tennessee.

Find out more about Kristie at www.kristiedean.com. Her Twitter is @kristiedavisdea, and her Facebook author page is @kristiedeanauthor.

Buy Kristie’s “On the Trail of the Yorks” at https://amzn.to/3gdhDsK