December 5: The ‘Boleyn’ Inscription at the Tower of London

A big thank you to Anne Boleyn Files follower Tara Ball for sharing with us this excellent article on an inscription at the Tower of London that has been linked to the Boleyns.

Over to Tara...

The Tower of London has many mysteries attached to its vast 1,000 year history. The central keep, the White Tower (also once known as Caesar’s Tower) was built as a palace and fortress between c.1078-1100. It was not long before it gained a reputation as a prison for traitors whose actions and intentions threatened the life of the monarch and the security of the realm. There is no historical document that is a complete list of prisoners who have entered the Tower’s formidable walls suspected of treason. A former Chief Yeoman Warder, A. H. Cooke, did produce a booklet for the exclusive use of his colleagues, the Yeoman Warders. From that booklet, Yeoman Warder Brian A. Harrison extended and revised a ‘Prisoner’s Book’ that Tower staff still use as a handbook today.

However, it is not just paper that is the only record of the fateful names. The very walls of the Tower itself bears the long-gone names of prisoners in the shape of graffiti and etchings etc. A sharp-eyed visitor to the Tower today will notice that barely a wall, passageway or stairwell has been left untouched by history. These markings vary from quotes and names to more detailed devices such as Hugh Draper’s 1561 intricate horoscope in the Salt Tower to the Dudley family crest in the Beauchamp Tower. These markings remind us that however their stories are told and retold, the prisoners were real people who steadfastly held onto their faith and principles at a time when they endured the toughest test of their lives; torture, execution and abandonment could await them once inside the cold stone walls of the Tower of London.

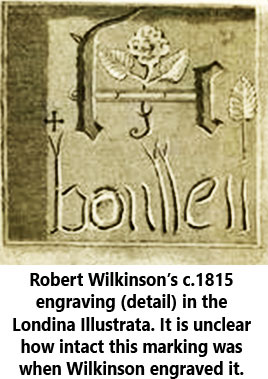

The Martin Tower is one of the buildings that holds some of the more famous graffiti of the Tower. Their presence is proof in itself that this two storeyed building (much rebuilt in red brick in the 17th century) was used as a prison, particularly in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. One particular marking is often sadly missed by the modern visitor but is one of the most significant. It is a simple marking by a staircase that leads to a later inserted third level. Worn away by time and curious fingers, it is now safely kept behind a secure panel of glass. A large ‘H’ is still clearly seen with a flower in its centre but a word etched underneath is harder to interpret: ‘bo..lle..’ are the only letters clearly seen with two vertical lines where a third letter should be and at the end of the word (see figure 2). Recently historians have believed it once said ‘boullen’, an alternative spelling of the name ‘Boleyn’. With the presence of the H above, it is commonly seen to being linked with the ever popular and romantical historical figure Queen Anne Boleyn.

She was the second wife of King Henry VIII and was imprisoned, tried and executed at the Tower on charges of adultery, incest and treason in May 1536. Seven men1 were accused and imprisoned with her, including her own brother, George Boleyn. Historians have pondered over who would have made this graffiti; was this a show of support or of their predicament, as it is generally accepted that all the accused were innocent and part of a plot to eliminate the Boleyn’s and their influence on the King which, they had held for ten years. With little evidence to go on, are we able to unravel the truth behind this remarkable piece of history left on the silent and cold stone?

The earliest record of this mark appears in a publication from about 1815 ‘Londina Illustrata’. A beautifully detailed print by Robert Wilkinson is accompanied by a brief, romantically written text. It reads that this is “the autograph of the unfortunate ANNA BOULLEN” who “even in her prison hours.. her affection toward the cruel HENRY.. presents a touching and melancholy proof” by the joining of her name with his initial with the royal emblems of the rose and thistle. The description ends “Could he have beheld her in this sorrowful and solitary labour, would he have felt any returning kindness? We fear not1. This piece was clearly designed to pull the heartstrings of the reader in favour of Anne Boleyn and pointing out Henry’s legendary cruelty. Unfortunately there is little truth to this text.

Today we know from the primary sources that Anne was never imprisoned in the Martin Tower, but was held in the long demolished Royal Apartments, built by King Henry III to the south of the White Tower in the Inmost Ward. It was only up until fairly recently that it was believed her prison had been the black and white timbered Tudor house on Tower Green, a stretch of lawn in the west of the Tower site, now known as the “Queen’s House”. Her name and initials also appear carved in a bedroom, thought to have traditionally been of her hand, but are now certainly false.

The Tower’s history of tourism was built on traditions and propaganda. Visitors and tours to the Tower of London have been recorded as far back as Elizabethan times and the traditional tour guides have always been the Yeoman Warders. In their role as guardians of the Tower, both of its history and operations, they have guided visitors through the curiosities it holds, such as the armoury, Royal Menagerie and the Crown Jewels. They told the spectators the tales behind the historical prisoner names but accuracy was not given close attention. Primary sources and records were not as easily obtainable as they are today and the Yeoman could only recite tales and legends they had heard of. Even today, their famous tours are for entertainment value, as each Yeoman Warder is required to have served in the military for twenty-two years and are not required to have an academic background. A lot of the early writers and chroniclers of history relied upon the Yeoman tours and took them at face value as fact, as proved in this case about Anne Boleyn imprisoned in the Martin Tower and carving her name. Due to the recent, more accurate research of historians, we now know this cannot possibly have been Anne’s own work.

It is often suggested that this could be a mark left by George Boleyn instead and that the Martin Tower served as his prison, rather than his sister’s. The truth is there is no record of where he was kept. The Prisoner’s Book does not tell us and although there is no evidence to agree, there is evidence to suggest that he was not. The other markings in the building all date much later than George Boleyn’s imprisonment. By 1671, it was used as a vault for the newly created Crown Jewels after the Restoration of the Monarchy and above the vault was home to the Keeper of the Crown Jewels and his family.2 At the time of George Boleyn’s imprisonment, it seems the building was uninhabitable and in poor shape. In 1532 (just four years before his arrest) it was recommended that a timber floor was needed, staircases and the roofs of the two turrets needed replacing2. Boleyn’s status required him to have comfortable accommodation, so this suggests that neither he or any other of the accused men would not have been held here, especially as payments are absent from the surviving accounts of the actual work done. Iron bars are still visible in the windows, demonstrating the security of this tower, but these were not inserted until 1596/73. It seems unlikely that the inscription is associated with either Boleyn sibling. Indeed the word may not even be ‘Boullen’ at all.

The inventory ‘Royal Commission on Historical Monuments’ (published in 1930) makes no mention of it being linked to the Boleyn’s. Instead it simply enters it as “bouttell” and says no more on its history4. The word ‘bouttell’ is from an old English word ‘bodl’ or ‘botl’ which, means a dwelling or a hall. If so, could this inscription be of no historical value at all, but simply a label in reference to the room’s function? Indeed, Londina Illustrata does call the room ‘Hall of the Regalia House’. Bouttell is also a possible surname (Bootle being the modern spelling as well as being a well-known English town in Merseyside). Could this possibly be the name of another prisoner who found themselves incarcerated in the Tower’s walls? Sadly not. Using the Prisoners’ Book, this name does not appear in the lists. However as the word in both Wilkinson’s engraving and photo evidence, the word is indecipherable. Using the most clearest letters, the word could spell ‘Bole’ or an equivalent spelling of. In the Prisoners’ Book, however, an entry does appear for ‘Mr. Boles’ (or Booles)5. Very little is known about him; he was imprisoned in 1571 and was still there in 1574. His fate is unknown and no source is given on him. He was part of the ‘Ridolfi Plot’. This plot’s aim was to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I and put her rival, Mary, Queen of Scots on the English throne. As cousins, each woman had a claim for the English throne and thus were rivals due to Elizabeth’s illegitimacy and their different religious beliefs. As a Catholic with French Royal blood, Mary was the figurehead for Elizabeth’s enemies and after abdicating in favour of her baby son, she had fled to England for support. Elizabeth dawdled on any decisions surrounding her fallen cousin, preferring to keep Mary in her control as best she could. A frustrated Mary however, was open to any offers to free her from Elizabeth’s grip and always had her eye on England’s throne.

The Ridolfi Plot aimed to marry Mary to the 4th Duke of Norfolk (a maternal relative of Elizabeth’s). Elizabeth’s intelligence network warned her of danger before the plot could be carried out. Norfolk was later executed.

The flower on the ‘H’ above the word engraved in the Martin Tower is unidentifiable. According to Londina Illustrata, both the rose and thistle are present in the graffiti but the thistle is absent from the engraving. Nevertheless it is worth pointing out that the Scottish thistle emblem was not used by the English royalty until the eventual succession of King James I, Mary’s son, upon the death of Elizabeth in 1603. The uniting the English and Scottish crowns also included incorporating each other’s emblems. Therefore the thistle would never have been used by Anne or George Boleyn.

If this engraving is one made by the prisoner ‘Mr. Bole’, the ‘H’ above his name could be linked as support for Mary Queen of Scots. The letter H is a strong symbol for Mary; she was a descendant of the founder of the Tudor dynasty, King Henry VII, her father-in-law had been King Henri II of France, her second husband had been Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley and with the Ridolfi plot, her fourth prospective bridegroom was Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk. Furthermore, she had once been in possession of a jewel known as the ‘Great H of Scotland’. This was a large jewel made of diamonds and rubies. Tradition said it had been given to her grandmother, Princess Margaret by her father, Henry VII, when she left for Scotland to marry King James IV of Scots. More likely it was actually a gift from her father-in-law, Henri II, at the time she wed his son the Dauphin. Upon her widowhood, she took it back to Scotland with her. When she was forced to flee Scotland in 1568, she had left her jewellery behind, having been confiscated by her half-brother, Regent Moray. When he was assassinated, Mary wrote requesting the return of the Great H from his widow in 1570 and again in 1571, around the time of the Ridolfi Plot. Did she plan to use the Great H once again if she gained the crown of England? Did the conspirators plan to use ‘H’ symbolically as some kind of banner for their cause? We do not know for sure but it is certainly a potentially powerful and well-connected symbol for supporting Mary, Queen of Scots.

As for the Great H, it eventually passed into the hands of her son, King James VI and I, who had it broken up and reformed as the Mirror of Great Britain. This jewel included the Sancy Diamond and is the only survivor of the jewel today and is displayed in the Louvre.

In conclusion we cannot know for sure how to correctly interpret this fascinating mark in the Martin Tower. My conclusion is that it is unlikely to be connected to either Anne or George Boleyn and is either a prop in the early, inaccurate yet entertaining tales of the Tower or it is indeed connected to another prisoner waiting to be rediscovered. What are your thoughts?

Tara Ball

Her Majesty’s Palace and Fortress The Tower of London is under the care of the Charity Historic Royal Palaces (HRP). The views and opinions are entirely the author’s own and are not affiliated with HRP. HRP is a self-funding charity and has suffered through the current COVID-19 pandemic. If you wish to support and make a donation you can find out about HRP’s crucial work on the official website www.hrp.org.uk.

Useful links:

To read HRP’s Coronavirus statement: https://www.hrp.org.uk/coronavirus-covid-19-statement/#gs.lio3jw

To make a donation: https://www.hrp.org.uk/support-us/#gs.liny1w

NOTES

1) Londina Illustrata (shortened title), William Herbert and Robert Wilkinson; c.1819-1825; v.II, p.115.

2) The Elizabethan Tower of London: The Haiward and Gascoyne Survey, Anna Keay; 1991; p. 36

3) ibid

4) Royal Commission on Historical Monuments East London, V, p.83 *see also The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn; Eric Ives; 2004 p. 424 note 34

5) Condensed Summary of Prisoners of The Tower, 1991 Revision, Yeoman Warder Brian A. Harrison; p.69