December 12

Thank you so much to author Alex Marchant for contrubuting today's Advent Calendar treat, I'm certainly going to be checking out Alex's books now!

A Topsy-Turvy Christmas, 1483

This week, as usual, I undertook the annual ritual of hefting the box of decorations up from the cellar in order to decorate our splendid Christmas tree. Rummaging in amongst the tinsel and ancient baubles (as ever feeling like Will Stanton – the lead character in my favourite book, The Dark is Rising – on Christmas Eve), I came across a little something I must have left in there specially when packing everything away last Twelfth Night. A newspaper cutting of a poem by poet laureate Carol Ann Duffy.

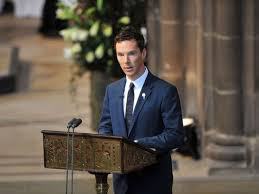

As a Ricardian, I have a soft spot for Duffy, whose poem ‘Richard’ was read by Benedict Cumberbatch at King Richard III’s reinterment in March 2015. (She later dedicated the poem to Philippa Langley MBE who led the search for the king’s grave as part of the Looking for Richard Project team.) I echo some of the imagery at a significant point in The King’s Man, the second book in my sequence telling the story of the real King Richard for children and young adults – The Order of the White Boar. I also used a line from it (with her permission) as the title for an anthology of short fiction inspired by the king that I’ve recently edited for sale in support of Scoliosis Assocation UK (SAUK) – Grant Me the Carving of My Name.

Here's a link to that poem: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/mar/26/richard-iii-by-carol-ann-duffy

This new poem, however, was not about King Richard, although it is entitled ‘The King of Christmas’. It begins:

‘Bored, the Baron mooched in his Manor

on the brink of belligerence. Life lacked glamour

and Christmas was coming. The Baroness,

past her best, oozed ennui, stitched away

at a tapestry...’

Here's a link to the new poem: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/dec/24/king-of-christmas-carol-ann-duffy-new-poem

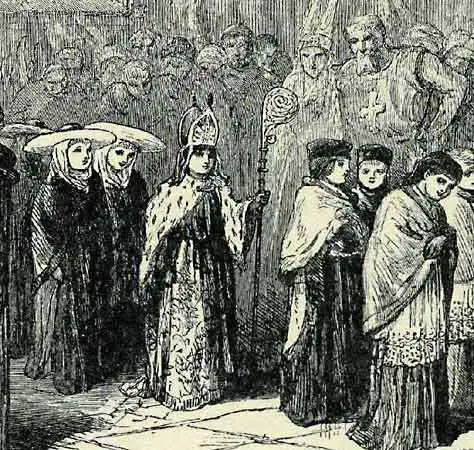

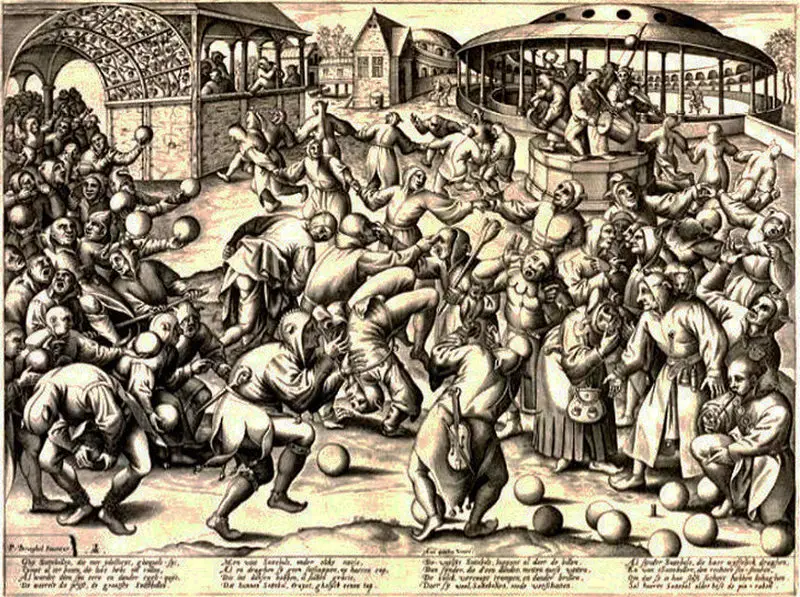

It tells of the day when the bored Baron decides to appoint a ‘Lord of Misrule’. This was a tradition in courts and noble houses across Europe, and also within the church hierarchy – whereby a lowly servant or peasant (or choir boy in the cathedral song schools) was named lord or bishop (or even pope) for the day or the season to take charge of the Christmas festivities.

Everything would be turned ‘topsy-turvy’ for that period, with the lowly in positions of power and the powerful subservient to them. In some cases the emphasis was on children having fun for a change, focused on the Feast of the Holy Innocents on 28 December, which memorialized the slaughter of children by King Herod in his attempt to get rid of the infant Jesus. The European counterpart of the ‘feast of fools’ became so raucous a drunken, cross-dressing festival aimed at turning power on its head that it was banned in the fifteenth century.

My main character in The Order of the White Boar and The King’s Man, twelve-year-old merchant’s son Matthew Wansford, is a former chorister at York Minster who enters King Richard’s service at Middleham Castle in the summer of 1482 when Richard is still Duke of Gloucester. Matt has left the Minster song school under a cloud that summer through no fault of his own (honestly!), but even while he was at the school, he always missed out on the custom of topsy-turvy as he would return to his family home elsewhere in York to celebrate the Christmas season – returning only to sing at the various services over the Christmas season.

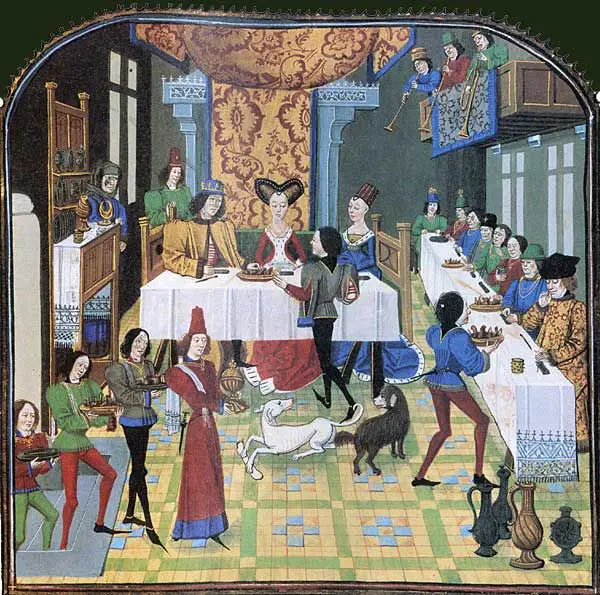

Matthew spends Christmastide in 1482 at the Palace of Westminster with Duke Richard and the family of his brother, King Edward IV, where:

I was always included with the rest of the guests, no matter how lowly, in the sumptuous Christmas festivities. In the whirl of that time – those days and nights of elaborate feasting, of courtly dancing, of minstrels, of jewelled gowns for the ladies, jewel-coloured velvets for the gentlemen, of gorgeously decorated chambers, draped with swags of greenery and berries, of laughter and jesting and masques – I saw a great deal of the royal family and their courtiers.

And on Twelfth Night,

the last day of Christmastide was marked by the most elaborate festivities. A fabulous banquet with more courses than I could number. Not one or two, but three dancing bears. Then troops of mummers performed for the assembled guests.

It was very different from the Bible stories of our Corpus Christi plays in York, but, may God forgive me, I enjoyed it as much. The jewelled costumes, colourful speeches, ribald songs, fantastical monsters fashioned from sumptuous fabrics stretched over wooden frames, the swordplay agile like dancing, the dances alight with fire-eaters, sword-swallowers, knife-jugglers. And with the dancing that followed under the still-flaring torches...

But a year later, in the winter of 1483/4, having once again had to move to a new residence (at the start of The King’s Man), Matt finally experiences a topsy-turvy time in the household of his new master, wealthy London merchant Master Ashley:

It was the start of a joyous run-up to the Christmas season, though, for me, one very different to that of the previous year, when I had been guest at the court of the old King. All the solemnities of religious services were interlaced with the customary feasting and gifts, but the highlight for me was the practice of ‘topsy-turvy’ on Twelfth Night.

I had heard tell of it at the York Minster song school, but, living always at home and not as a boarder at the school, I had never been a part of it, or seen the Dean serve the choristers and canons at table, or any other of the customs involved. So to witness Master Ashley don rough clothes and place an apprentice cap upon his head, and Mistress Ashley tie a housewife’s apron about her oldest gown, and both carry trays of meat and drink to tables, and bow to us boys and journeymen as they served us and poured our ale – and even sing for us during the meal, poke the huge Yule log in the hearth and clear away the empty dishes – it was all remarkable to me. It was a tradition in such households across the city and beyond – although it never reached as far as my father’s house in York’s Stonegate.

Matthew writes of it to his good friend Alys, now part of the household of Elizabeth of York, with such enthusiasm that she decides to suggest the same idea to Duke Richard (by now King) and his wife Queen Anne the following Christmastide. Sadly, by then, in December 1484, a great tragedy has befallen the royal family and Alys doesn’t remember until it’s too late. Perhaps, however, in the circumstances it would hardly have been appropriate. And a year later ... well, a year later, everything had changed in England, and Matthew’s and Alys’s lives will never be the same again...

About Alex Marchant

Born and raised in the rolling Surrey downs, and following stints as an archaeologist and in publishing in London and Gloucester, Alex now lives surrounded by moors in King Richard III’s northern heartland, working as a freelance copyeditor, proofreader and, more recently, independent author of books for children aged 10+.

Her first novel, Time out of Time (due out 2019), won the 2012 Chapter One Children’s Book Award, and her second was put on the backburner in 2013 at the announcement of the discovery of King Richard’s grave in a car park in Leicester. As a Ricardian since my teens, that momentous announcement prompted me to write a novel about the real Richard III for older children (there being no such book available), and so The Order of the White Boar (with its sequel The King’s Man) was born.

You can find out more on her website https://alexmarchantblog.wordpress.com