On Sunday 10th April 2016 Anne Boleyn hit the news with articles in the Sunday Times and Mail Online claiming that a copy of a lost portrait of Anne Boleyn had been found by Alison Weir.1 Now, this wasn’t news to everyone as Weir had shared her eBay find on her Facebook page and that had sparked off discussions on her page and other Tudor history Facebook pages, groups and Twitter accounts.

What was this eBay find?

Well, it was a listing for “Photo of a print: Anne Boleyn portrait from the Holbein Room at Strawberry Hill”. The seller, Mr Howard Jones, was selling photos of a print he owned and in the description, he stated:

“Walpole’s Tudor painting had been incorrectly identified as Lady Joanna Bergaenny [sic] who died before 1505. The initial A on the necklace, the two additional initials and other clues suggest this is a ‘new’ and one of the best surviving portraits of Queen Anne. Boleyn. An engraving of Walpole’s painting had earlier been made in 1798. This is a later more detailed copy made after the Strawberry Hill sale of 1842. Additional information regarding this identification and the provenance of the Tudor painting (by, or after Holbein?) will be sent with the photograph.”2

I purchased a photo and started corresponding with Mr Jones regarding his print, while also researching the print, related prints and the original portrait, and contacting people with expertise in art and costume. Mr Jones told me that the re-identification of the print, from Joan/Joanna (née Fitzalan), wife of George Nevill, Baron Bergavenny, was his own and that it was based on the letters of the necklace being A, B and R – which he took to stand for Anne, Boleyn and Rochford – and the British Museum Print Room telling him it was a Victorian fake of Anne Boleyn. The information he sent with the photo stated that the original portrait was known as Lady Bergavenny, that it was given to Horace Walpole by Lady Beauclerk, daughter of the Duke of Marlborough, that it used to hang in the Holbein Rooms at Strawberry Hill, that the sitter’s necklace had three initials A, B and R, that there is a figure of 8 on the necklace and a swelling on the sitter’s neck, that the sitter has almond-shaped eyes and that the sitter’s facial features match other portraits of Anne Boleyn, such as the Radclyffe portrait/Hever Rose portrait and the National Portrait Gallery D21020 engraving by Robert White – see http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw91121/Unknown-woman-formerly-known-as-Anne-Boleyn?

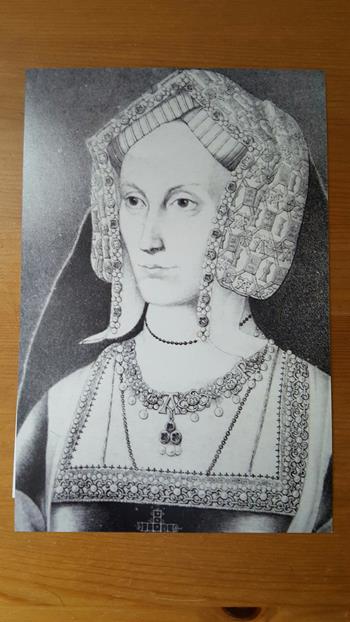

Here is the photo I received, which unfortunately was not a photo of the print but a photo of part of the print.

Alison Weir agreed with Mr Jones’s re-identification and, according to the Sunday Times, believed that the original portrait, which has not been found yet, “may have been painted to mark Boleyn’s coronation in 1533.” Weir believes that the A, B and R stand for Anne, Boleyn and Regina (Queen) and noted that the A on the necklace and hood resembled the A worn by Elizabeth, the future Elizabeth I, in the Family of Henry VIII painting. The article also stated that “Weir thinks the carnation held by the sitter in the engraving is also significant. The flower symbolises love and may derive from the word coronation” and quoted Weir as saying “Put all this together [and] it does look as though this may be a portrait of Anne Boleyn painted to mark her marriage and coronation.” Tracy Borman, joint-chief curator for the Historic Royal Palaces said that she was also “very convinced”.3

I’m not convinced and neither are the experts I consulted. While we cannot say that it is definitely not Anne Boleyn, the evidence so far, in our opinions, just does not point to it being so. I will now share our research.

The Print and Portrait – Provenance

Mr Jones, in Facebook comments and in emails has stated that “the provenance question is silly” but anyone who watches “Antiques Roadshow” or “Fake and Fortune” will know how important provenance is, not only in determining the value of a piece of art but also in identifying the artist or sitter. The National Portrait Gallery has produced fact sheets about researching portraits and provenance is listed as one of the factors that should be researched: “Tracing the history of the ownership or provenance of a portrait can provide further research leads” and “knowing who originally owned a portrait can sometimes help us to identify the sitter as portraits”.4 So, I got digging!

Howard Jones’s print is one of several based on a painting which, as Jones states, was given to Horace Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford, by Lady Diana Beauclerk (née Spencer, 1734–1808), daughter of Charles Spencer, 3rd Duke of Marlborough. Diana was a maid of honour to Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, and an artist. I haven’t been able to find (yet!) how Diana got hold it. In A description of the villa of Mr. Horace Walpole, youngest son of Sir Robert Walpole Earl of Orford, at Strawberry-Hill near Twickenham, Middlesex. With an inventory of the furniture, pictures, curiosities, etc. (1784),5 I found a mention of the painting in the “more additions section”: “Johanna lady Abergavenny; vide Royal and Noble Authors: a present from miss Beauclerc, the maid of honour”. This was a reference Walpole’s book Royal and Noble authors in which he included Joan, Lady Bergavenny, as an authoress of prayers, which was a mistake as he meant Frances, wife of Henry, Lord Bergavenny. The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University, state that the portrait was kept in the Holbein Chamber of Strawberry Hill and that in 1774 its description was “unidentified” but in 1784 its description was “Johanna lady Abergavenny”.6

In 1842, Walpole’s Strawberry Hill Collection was sold by his heirs, dispersing thousands of paintings, drawings, prints, pieces of furniture, books, manuscripts, ceramics etc. around the world. In the sale catalogue is a description of the painting given by Lady Diana Beauclerk to Walpole:

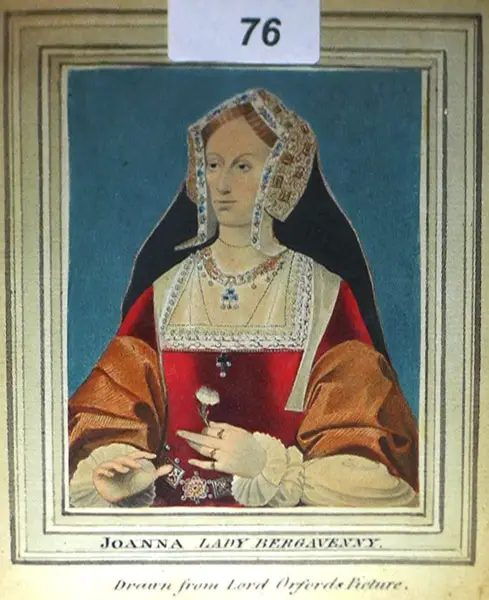

“This is a pleasing portrait of a woman in middle life, handsomely attired in the costume of Henry VIII’s reign, and holding a flower. The network of her head-dress is filled with the letters I [note: I was used for J too] and A, the initials of her maiden name, in alternate rows: and she wears a splendid necklace, which has an A in the centre and at each side a B standing for Bergavenny, as the title was then written…”7

The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University, state what happened to it at the sale:

“Provenance: Gift of Lady Diana Beauclerk to Horace Walpole; 1842, Strawberry Hill London Sale, day 20, lot 76[sold] bt Jarman, £21.00.00.”8

This could be John Jarman, a London dealer of curiosities. It passed from Jarman on to Ralph Bernal, being listed in Catalogue of the celebrated collection of works of art, from the Byzantine period to that of Louis Seize, of that distinguished collector Ralph Bernal as:

“The celebrated Lady Johanna Abergavenny, in a crimson dress with yellow sleeves, a gold head-dress embroidered jewelled girdle ornament her dress; she holds a pink in her left hand – in tortoiseshell frame – half-length – 16 in. by 12 in.”9

I’ve been unable to trace its whereabouts after that but art historian Dr Bendor Grosvenor states in his blog post on the subject that it is not lost and that he’s seen a colour photograph of it. He was asked to look into whether it might be Anne Boleyn and he explains: “Our belief at the time was the sitter was most likely not Anne Boleyn, though the tedious thing is I can’t now remember all of our conclusions. There was nothing in the way of provenance, or traditional identification, to lead us down that path. As far as I recall, there was no matching necklace in any Royal Tudor jewel inventory. But I do remember paying attention to the other motifs in the headdress, and not being able to connect any of them to Anne Boleyn.”10

As I have said there are several prints based on the portrait and they are all rather different – see above. As well as the one belonging to Howard Jones (top left), which he describes his as “a Victorian antique print, or Mezzotint” dating to after the 1842 sale, there are the following versions:

- Bottom left – Joanna, Lady Bergavenny, gray wash:13.7 x 10.5, by G P Harding, from A Description of the Villa of Horace Walpole, 1784 (Kirgate’s extra-illustrated copy), Strawberry Hill Press. From http://images.library.yale.edu/walpoleweb/oneitem.asp?imageId=lwlpr17849

- Bottom right – Joanna, Lady Bergavenny, stipple:18.9 x 14.1, by S Harding after G P Harding, published 1798. From http://images.library.yale.edu/walpoleweb/oneitem.asp?imageId=lwlpr17850

- Top right – An Italian version by Innocenzo Geremia in the British Museum which dates to 1806, stipple: 188mm x 140mm. It is described as “Portrait of Joan, Baroness Bergavenny; half length looking to left; wearing English gable hood, golde girdle, cross and embroidery decorated with her initials, and holding flower; illustration to Walpole’s “Royal and Noble Authors”. 1806

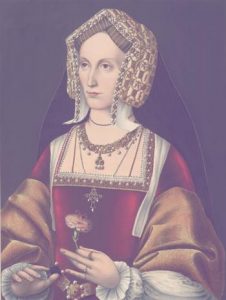

- A colour version of Mr Jones’ engraving by Henry Shaw in the British Museum (see main picture at the top right of this article) which dates to c. 1820-1868, colour, aquatint: 245mm x 185mm. It is described as “Portrait of Joan, Baroness Bergavenny; half length looking to left; wearing English gable hood, gold girdle, cross and embroidery decorated with her initials, and holding flower; from painting at Strawberry Hill.” It also says “Lettered below image with title”. It was acquired by the museum in 1868. click here to view it on the British Museum website.

- Watercolour version (see below) – from http://www.the-saleroom.com/en-us/auction-catalogues/criterion-auctioneers/

As you can see they are all very different – in style, in the appearance of the sitter and also the details shown in them. I think they tell us more about the era in which they were produced than the portrait they were based on. One interesting difference is the necklaces – with some not showing the letters and the later versions, the coloured British Museum one and the one belonging to Howard Jones, having the letters A, B and R, rather than the A and two Bs described as being on the necklace in the original portrait.

That’s as far as I’ve got somewhere with my research on the prints and original portrait.

“Clues” in the print

Howard Jones, in an email to me, wrote of the print having clues that pointed to Anne Boleyn as the sitter. I assume he was referring to the letters, which he took to mean Anne, Boleyn and Rochford, and that Weir takes for Anne, Boleyn and Regina, and the gillyflower, also known as a pink or carnation. Flowers, plants and trees, in medieval times and Renaissance art, were used as symbols. Think back to Ophelia in Act 4 Scene 5 of Shakespeare’s Hamlet:

“There’s rosemary, that’s for remembrance. Pray you, love, remember. And there is pansies, that’s for thoughts….”

In The Garden of the Renaissance: Botanical Symbolism in Italian Painting, Mirella Levi D’ancona writes “According to custom spread from the Netherlands, the carnation, or its variation, the pink, was worn by the bride on the day of her wedding and the groom was supposed to search her and find the pink. For this reason the pink or the carnation became a symbol of marriage and were often shown in pictures of newly-weds or betrothed.”11

In its description of a 16th century painting known as “A young man holding a carnation”, the Victoria and Albert Museum state: “Carnations or pinks, especially when red, were symbols of betrothal, probably originating in a Flemish wedding custom. In portrait painting especially of the 15th and 16th centuries, when held in the sitters hand it signifies betrothal. A similar, earlier example of the Italian type is Andrea Solario’s Man with a Pink ca. 1495 (London, National Gallery).”12

According to another source, gillyflowers are also “associated with springing from the Virgin’s tears and therefore presage the Passion of Christ. The Virgin of the Pinks depicts Christ holding them in his hand.”13 Still another source gives the following meanings: red carnation: my heart aches for you and admiration, white carnation: innocence, love and devotion, pink carnation: I’ll never forget you, yellow carnation: you disappoint me, rejection.14

Art historian Melanie V. Taylor gives examples of other portraits depicting sitters holding pinks. The first is Raphael’s Madonna of the Pinks, which you can see at https://upload.wikimedia.org/ and which is now in the National Gallery.

In the Hever Castle portrait of Arthur, Prince of Wales, he holds a similar flower (see above). This portrait was discovered in the early 1990s and is by an anonymous member of the Anglo-Flemish School. Dendrochronology supports the idea that this was painted at the time of Prince Arthur’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Van Eyck’s painting of c.1436 of a man holding a pink was also probably painted to celebrate a forthcoming marriage, which demonstrates the visual trope of using a pink as a symbol of marriage – see https://upload.wikimedia.org/

Likewise, it is possible that the Holbein’s portrait of Georg Gisze now hanging in Gemäldgalerie, Berlin also contains references to a forthcoming marriage by the vase of pinks on the table, but like all things Holbein, this painting has much more than a simple visual aid to the sitter’s marital status – see https://commons.wikimedia.org/

The only thing that I’ve found about these flowers being linked to coronations is an article on carnations on Wikipedia which says: “Some scholars believe that the name “carnation” comes from “coronation” or “corone” (flower garlands), as it was one of the flowers used in Greek ceremonial crowns. Others think the name stems from the Latin “caro” (genitive “carnis”) (flesh), which refers to the original colour of the flower, or incarnatio (incarnation), which refers to the incarnation of God made flesh.”15 Perhaps the name comes from “corone”, but I haven’t found any 16th century link between the flower and coronations.

Costume

I have known Bess Chilver, a costume expert and re-enactor, for many years now and I contacted her as soon as Alison Weir shared her Ebay find on Facebook. We’ve been discussing the sitter, her costume and jewels ever since, as well as sharing our thoughts on social media. Bess is working on a detailed article about the sitter’s costume and jewellery, and I will share that when she has completed it. For now, I can tell you that Bess’s knowledge of costume of the period – and she has also discussed this with other costume experts – means that she can date the costume to between 1520 and 1525 and it is the costume of a wealthy and high status lady. What is the evidence for this?

- The shape and style of the English gable hood – The hood worn by the sitter in these prints dates to the early 1520s. The gable hood evolved over time, just like the French hood. As you can see in the prints, the lappets (the bands that you see hanging down) almost brush the shoulder. By the 1530s, as you can see on the Holbein portrait of Jane Seymour and the 1534 Anne Boleyn medal, these were much, much shorter.

- The neckline – The sitter’s dress has a much narrower square to its neckline than the wider neckline Anne is wearing in the medal, and which was fashionable in the 1530s. If you look at the National Portrait Gallery portrait of Anne Boleyn, which dates to her daughter’s reign, you can see that the neckline is so wide that it is almost off the shoulder.

- The white bands – If you look at the prints, you can see that the sitter has a band of white fabric coming down over each shoulder and ending just below the bust. These bands were fashionable in the 1520s but had disappeared by the 1530s. Anne is not shown wearing them on the 1534 medal, Jane Seymour does not wear them in her portrait and Katherine of Aragon starts to lose them in the late 1520s/early 30s.

If the print is a coronation portrait, as Alison Weir states, then Anne Boleyn is extremely unfashionable – she is wearing fashion that is ten years out of date! Would a queen allow herself to be depicted wearing out-of-date clothes? I don’t believe so. She would have the wealth and status to be up-to-date and she would be setting the fashion.

But could it be a 1520s image of Anne? Well that doesn’t make sense either, unfortunately. Bess points out that the sitter’s costume, with all the embroidery on the hood, and her display of jewellery shows that she is a wealthy and high status woman. In the early 1520s, Anne Boleyn was not high-status. She didn’t become a marchioness until September 1532. But wasn’t her father a king’s favourite and a wealthy man in the 1520s? Yes, but his daughter just did not have the status to be painted in this way. Bess explained this really well on Facebook so I will quote her words here:

“There were many people who were wealthy. The first Millionaire lived in Lavenham and was a Merchant of wool, though he too was also knighted. However, what then comes into play is something called Sumptuary laws. These were strict and were designed to ensure that people dressed according to their status in life. A gentlewoman, daughter of a mere knight, does not dress as if she is a duchess. It would be insulting to those at court. Thomas Boleyn, though he maybe wealthy, is still not in a position to rock that particular boat even in the 1520s […] dressing his daughters to rival the Queen at the time is not one is he is going to risk. As a Maid of Honour (NOT lady in waiting) the girls would have also been expected to dress to a specific standard and not step over that line to be better dressed than others who are higher ranking than they are. It was one thing to be spoken of as one who stands out due to cut of dress (Anne did have more French styled gowns) but it would have been a completely different thing to have been spoken of because one is dripping in jewels and fabrics that are above one’s station in life.”

The Jewellery

As has been pointed out, the sitter shown in Mr Jones’s print is wearing a necklace with a central A and then a B and an R. I know from my own research into Anne’s jewellery that a list of “Certen jewelles of the Kinges highnes which be trussed and inclosed within a faire deske of wodde, maser colour” (LP xii. Part 2. 1315) included rings and jewels with H.A. on them, a ring engraved with MOSTE (Anne’s motto was The Most Happy) and a brooch with R.A. in diamonds for Regina Anna. There were also rings with H. I. for Henry and Jane, an I being used in that period for a J too. It was fashionable in Henry VIII’s reign to use letters or ciphers in jewellery, and Henry also made use of them in buildings. We know that Hans Holbein designed a number of pieces of jewellery and ciphers with letters entwined. In the 15th century, Margaret of York, Duchess of Burgundy, was painted with a B pendant, very similar to the B of Anne Boleyn’s famous B necklace, attached to her head-dress so they were fashionable then too.

However, letters did not have to be related to the person’s name. As Bess pointed out in her Facebook comments to people saying things like “it must be Anne because of the A and B”, letters in pre-Reformation England could have religious significance and could be abbreviations for Latin phrases relating to Christ, such as the “IHS” that Jane Seymour is depicted as wearing in her portrait. The “IHS” monogram refers to the Holy Name of Jesus. An intertwined A and M could be used as a monogram of the Virgin Mary with Auspice Maria meaning “Under the protection of Mary”. As Bess, notes, an ‘A’ on its own “could refer to ‘Alpha’ for all we know”.

While Anne Boleyn could make use of an R after her marriage to Henry VIII, when she is Anne Regina, she couldn’t have made use of an R in the early 1520s. Her father may have become Viscount Rochford in 1525 but Anne was not entitled to use the title of “Lady Rochford” then as only the daughters of dukes, earls and marquesses could style themselves as “Lady ….”. Only from December 1529, when her father was made Earl of Wiltshire, could Anne call herself Lady Rochford. Bess explains that Thomas Boleyn’s elevation to earl “allows his daughter Anne to be style Lady Anne Rochford as she takes the surname from his secondary title of Viscount Rochford. His son George is styled by that secondary title so becomes Viscount Rochford”.

But the letter R isn’t even in the original portrait! As I said earlier, the description of the original portrait says that the sitter “wears a splendid necklace, which has an A in the centre and at each side a B standing for Bergavenny”. So, let’s forget about the R.

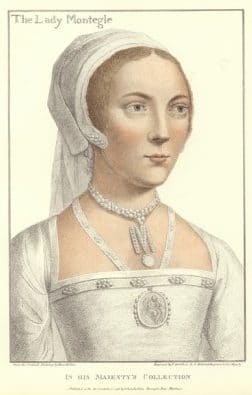

What about the “A” and “B”s? Surely, they scream Anne Boleyn! Well, no, they don’t. If they aren’t religious ciphers then they are more likely to be family names, i.e. surnames or titles. I was discussing this with art historian Melanie V. Taylor and she said that we have to remember the status of women at this time. She explained to me that a 15th or 16th century woman is not going to draw attention to her first name, she is going to draw attention to her family name and title as that is what she was defined by. Mary Brandon, Baroness Monteagle, is depicted wearing an M necklace not for Mary but for Monteagle, and Margaret of York, Duchess of Burgdundy, wears a B for Burgundy. An A in the centre the necklace, and so the prominent letter, might make sense for a Queen Anne, but not for a noblewoman named Anne.

And what about the “I”s and “A”s on the hood? Why would Anne Boleyn use an “I” (which was also used for a “J”)?

Age of sitter

We don’t know Anne Boleyn’s exact birth-date but historians believe that she was born in the first decade of the 16th century, with 1501 and 1507 being the dates argued. As we have established through dating the costume, if the missing portrait is contemporary then it was painted in the early 1520s. Anne returned to England from France in late 1521 or very early 1522 when she was either about 20/21 or 14/15. At this time she was a young woman in her prime, not “a woman in middle life” which is how the sitter of the original portrait was described in 1842.

If we set aside the dating of the costume and go with Weir’s idea of it being a coronation portrait, then Anne would have been about 32 or 26. You might call that middle-aged for the Tudor period, but would Henry and Anne want Anne, the new queen, depicted as middle-aged and a frump too? Portraiture was propaganda, it wasn’t about realism when it came to royalty.

And why is her pregnancy not obvious? I’m sure that 16th century costume could hide a pregnancy quite well but Anne was 5/6 months pregnant in June 1533 and her pregnancy was a huge deal, so wouldn’t a coronation portrait have celebrated this? Anne’s coronation procession alluded to her pregnancy and fertility – her falcon badge, with the falcon on a tree stump from which white and red roses spilled, a pageant with St Anne surrounded by her children – and the monarch’s crown, the crown of St Edward, was used at Anne’s coronation which has been taken by some to signify that Anne’s unborn child was actually being crowned. Where are the allusions to pregnancy and fertility here?

Appearance

There were many, many comments on social media when this engraving was shared about how it looked like Anne. People were posting it side by side with various portraits of Anne Boleyn, forgetting that none of these portraits are contemporary. Unfortunately, we don’t know what Anne looked like. The one authentic contemporary image of Anne is the 1534 lead medal which is significantly damaged and, as G W Bernard points out, “is consequently not that helpful as an indication of her appearance”.16 Lucy Churchill studied the medal in detail to make a beautiful replica and the late Eric Ives wrote of how Lucy’s replica “has brought us as close to the real Anne Boleyn as we shall ever be able to get”. As Lucy states on her website, “we can deduce that Anne Boleyn clearly had a long face with high cheek bones, and a prominent chin”,17 but we can’t tell more than that. How can we compare this engraving to the medal? All four versions are very different – just look at the noses for starters.

Howard Jones pointed out the swelling on the neck of his version and I’ve also seen comments about this online. I don’t believe the sitter does have a swelling – there certainly isn’t one in the other versions – but even so, that does not point to it being Anne Boleyn. A now-lost, hostile anonymous account of Anne Boleyn’s coronation states that “She wore a violet velvet mantle, with a high ruff (goulgiel) of gold thread and pearls, which concealed a swelling she has, resembling goitre” but it also says that “a wart disfigured her very much” and “her dress was covered with tongues pierced with nails”, descriptions that don’t fit with any of the other contemporary accounts of her coronation or her appearance.18 Nicholas Sander, a Catholic recusant writing fifty years after Anne Boleyn’s time as queen, wrote of how Anne wore high-necked dresses to cover a swelling on her throat, but he also described her as having an extra finger and a projecting tooth. Sander was only six years of age when Anne was executed and he never met her. His description, again, is not backed up and Anne was not known for wearing high-necked dresses.19

Conclusion

At the end of the day, we’re discussing a mid to late 19th century copy of a portrait we don’t have at the moment, although Bendor Grosvenor knows that it is still in existence and has seen a photograph of it. He states that there was nothing in his research – and he IS an art historian and an authority – that linked it to Anne Boleyn. Grosvenor writes: “The picture was once at Strawberry Hill, and we must tempted to assume that if there really was any historical chance this sitter might have been Anne Boleyn, then those old iconographical optimists of the 18th and 19th Centuries would have labelled it such” and I have to agree with him. We don’t know what information came with the original portrait. Did it become known as Joanna, Lady Bergavenny, because of the letters alone or was there a provenance that supported that identity? We don’t know. The letters do fit that identification – the prominent “A” and “B”s for her family name Arundel and title Bergavenny, and then the not so prominent “I/J” for Joanna or Joan. But then the costume dating might not point to Joanna, in that she is said to have died around 1508. It could be a posthumous portrait though.

When I contacted the British Museum about Mr Jones’s print and the prints they have in their collection, they stated: “we stand by the identification given on the database of the two prints”, i.e. Lady Bergavenny.

It turns out the portrait is not lost anyway, it’s in a private collection, and also this print owned by Mr Jones is not a discovery, the British Museum acquired their coloured copy of it in 1868 and it’s in their department of Prints and Drawings.

In my opinion, and I know Bess Chilver and Melanie V. Taylor agree with me, there is not one good reason to re-identify this image as Anne Boleyn. The “clues” in the prints do not point to Anne Boleyn – the costume is wrong, the age of the sitter is wrong, the letters are wrong, the status of the sitter is wrong… If it is meant to be Anne Boleyn then it has been painted much later by someone unaware of the costume of the period and the rules governing what people wore. I can’t say it’s definitely not Anne Boleyn – I don’t have the portrait and I am not a qualified art historian or Tudor portrait specialist – but my research and the expertise of those I’ve contacted regarding the print do not point to it being Anne. Further research into the original portrait is needed.

I will share Bess Chilver’s article as soon as she has finished it – stay tuned!

Other articles on this (I’ll add them here as I find them):

- Is this image Anne Boleyn or Joan Bergavenny? by art historian Melanie V. Taylor

- A new lost portrait of Anne Boleyn? by art historian and portrait expert Dr Bendor Grosvenor

- This is not Anne Boleyn: The “New Portrait” controversy.

Update: Alison Weir has just written an article on her website too – scroll down the page at http://alisonweir.org.uk/books/bookpages/more-lady-in-the-tower.asp to “A new image of Anne Boleyn?”.

Notes and Sources

A big thank you to Bess Chilver and Melanie V. Taylor for their help and advice with this article. Thank you also to the British Museum Print Room.

- ‘Lost Boleyn head’ rolls up on eBay, The Sunday Times, 10 April 2016, The lost head of Anne Boleyn? Expert says 16th century artwork which turned up on eBay is portrait of Henry VIII’s second wife Mail Online

- Photo of a print: Anne Boleyn portrait from the Holbein Room at Strawberry Hill, eBay.co.uk, March and April 2016, seller:thimble21, Howard Jones.

- The Sunday Times, 10 April 2016.

- Researching Early British Portraiture and Understanding the History of Ownership

- A description of the villa of Mr. Horace Walpole, youngest son of Sir Robert Walpole Earl of Orford, at Strawberry-Hill near Twickenham, Middlesex. With an inventory of the furniture, pictures, curiosities, etc.

- The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

- The Gentleman’s Magazine by Sylvanus Urban, Gent., Volume XVIII, July to December Inclusive, London, William Pickering, John Bowyer Nichols and Son, 1842, p. 148.

- The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

- Catalogue of the celebrated collection of works of art, from the Byzantine period to that of Louis Seize, of that distinguished collector Ralph Bernal

- A new lost portrait of Anne Boleyn?

- D’Ancona, Mirella Levi (1977) The Garden of the Renaissance: Botanical Symbolism in Italian Painting, L. S. Olschki.

- A young man holding a carnation, http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O127730/a-young-man-holding-a-oil-painting-unknown/

- Symbols and Meanings in Medieval Plants, https://livinghistorytoday.com/2010/04/12/symbols-and-meanings-in-medieval-plants/

- Flower Meanings A-Z, http://scovey.photium.com/page87015.html

- Dianthus caryophyllus, Wikipedia.

- Bernard, G W (2011) Anne Boleyn: Fatal Attractions, Appendix: The Portraits of Anne Boleyn.

- https://lucychurchill.wordpress.com/2012/05/14/the-moost-happi-portrait-of-anne-boleyn-a-rec/

- LP vi. 585

- Sander, Nicholas, Rise and Growth of the Anglican Schism (1585), p25.

Images:

- Joanna, Lady Bergavenny, courtesy of the British Museum, made by Henry Shaw c. 1820-1868, colour aquatint, museum number 1868,0208.233.

- Photo by Claire Ridgway of the photo that was sent by Howard Jones, the owner of the print.

- 4 images – top left is Howard Jones’s print; top right is Lady Bergavenny by Innocenzo Geremia, 1806, courtesy of the British Museum, museum number 1868,0208.233; bottom left is Joanna, Lady Bergavenny, by G P Harding, “in A Description of the Villa of Horace Walpole, 1784 (Kirgate’s extra-illustrated copy) .Strawberry Hill Press”, from http://images.library.yale.edu/walpoleweb/oneitem.asp?imageId=lwlpr17849; bottom right is Joanna, Lady Bergavenny by S Harding after G P Harding, published 1798. From http://images.library.yale.edu/walpoleweb/oneitem.asp?imageId=lwlpr17850.

- Lady Bergavenny, watercolour, lot 76, Criterion Auctioneers, from http://www.the-saleroom.com/en-us/auction-catalogues/criterion-auctioneers/catalogue-id-criter10421/lot-df25cc33-0b3e-4907-9ae4-a532014147c5 which shows it lying down, photo manipulation by Tim Ridgway.

- Arthur, Prince of Wales, Hever Castle portrait, from Wikimedia Commons.

- Jane Seymour by Hans Holbein the Younger, Wikimedia Commons.

- Anne Boleyn 1534 medal, British museum, museum number M.9010.

- Anne Boleyn, National Portrait Gallery, Wikimedia Commons.

- Mary Brandon, Lady Monteagle, Bartolozzi after Hans Holbein – I own a copy of this.

- Margaret of York, Duchess of Burgundy, Wikimedia Commons.