Today I am happy to welcome Lissa Chapman, author a new book, Anne Boleyn in London, to the Anne Boleyn Files with a guest article. A big thank you to Lissa!

Today I am happy to welcome Lissa Chapman, author a new book, Anne Boleyn in London, to the Anne Boleyn Files with a guest article. A big thank you to Lissa!

Anne Boleyn is one of the historical figures whose images are instantly recognisable and whose reputations are remade for each generation. Along with a few facts (she was the second of the six wives of King Henry VIII. She was the mother of Elizabeth I. She was beheaded), her name is surrounded by a constantly shifting cloud of myths, rumours, romanticisms and insults. The word “infamous” is routinely applied to her. And the myths make for some unwholesome reading – any accusation not made at the time of her trial and execution was enthusiastically invented in the succeeding years. The adultery, incest and poison plots were soon joined by witchcraft, teenage promiscuity and a grotesque array of physical deformities to match her supposed moral failings. Oh, and everybody hated her and she was jeered at and attacked any time she showed her face. Variations on all these themes are still current.

The claim that Anne Boleyn was universally unpopular began as soon as her name became known outside Court. Once it became clear she was not merely the latest “lady whom the King serves” – the courtly term for anything from a passing flirtation to a full-blown affair – the usual reaction seems to have been scepticism followed by outrage. The chorus of disapproval was swelled by ambassadors, by churchmen, and from foreign courts. Mario Savorgnano wrote home to Venice in 1531 that the one flaw in the character of Henry VIII, whom he claimed greatly to admire, was that he was totally dominated by Anne Boleyn, and was threatening to leave his wife of 22 years for her – but the lords and people of England would never accept a change of Queen. And he was not alone in his claims. Eustace Chapuys was the recently arrived Ambassador of the Emperor Charles V, who was the nephew of the soon-to-be-discarded Catherine of Aragon. Chapuys was in no doubt that his role included not only reporting events but championing Catherine in any way he could – and as time went on he was to become genuinely and deeply fond of her. Unfortunately for posterity, his partisanship makes him a questionable witness, as it is clear that he was only too keen to accept any story that reflected badly on Anne Boleyn in any way possible – and that included tales of her unpopularity with the common people.

In theory, the business of “the people” in the 1530s was to work, pray and obey, not to have opinions. Children were to obey parents, wives their husbands and servants their masters – and in the Tudor world everyone had an overlord, the person the next step up the pecking order. The reality was often somewhat different, and Henry VIII, like other monarchs before and since, was acutely aware of the mood on the London streets. Civil war was still well within living memory, and any sensible sovereign and his council needed the reassurance of a peaceful and, preferably, prospering, capital city. The nearest approach to public unrest during the current reign had been the Evil Mayday riots of 1517 – this was an uprising in protest against the wealth of many of London’s foreign, and in particular, French residents. In the event no one had been killed, although there was much damage to property, but thirteen of the rioters, including some teenage boys, were hanged, drawn and quartered in Cheapside, and many of the rest made to take part in a theatrical display of repentance in Westminster Hall before being formally pardoned.

In the following years, it suited the City authorities as much as it did the King for London to be trouble free – riots were bad for business. And when the next real threat to the settled order arrived, it did so quietly and gradually. The seeds of the movement that would become the Reformation had been sown many years before. Now the shoots began to grow. Forbidden copies of the Bible in English started to arrive, carried by returning merchants. Londoners began to attend reading groups where, to the horror of both church and civil authorities, they started to form their own opinions. Thomas More, after his appointment as Lord Chancellor, was foremost of those who sought to root out what were perceived as heresies. To the King, the problem lay in handing the tools of thought and articulate questioning to subjects. He was never to understand that the genie of reform, once out, would never again be confined. Famously, he believed that he could retain the Catholic church but without the Pope. At the time Anne Boleyn’s name began to have significance, the movement for reform of the church was still at an early stage of growth – but there were already strong, unofficial networks linking those of shared sympathies. And certainly Anne and her brother George, along, possibly, with their father, were among those interested in the question.

Tudor London was a place of whispers. It was to be more than three centuries before universal schooling was on the agenda of even the most extreme radical, and no one knows exactly how many Londoners were literate in the early sixteenth century. There were schools, monastic, ecclesiastical and secular, from some of the great cathedral schools to small informal groups of children taught in private homes. And it seems that mothers often taught their children to read – writing was a separate skill, involving expensive equipment, and it is likely that many Londoners who could sign their name only with an “x” were in fact able to read. But except for the privileged, there was little available on which to practice their skills. It was less than half a century since William Caxton had brought printing to London, and books were still prohibitively expensive, as was paper. Most news travelled by word of mouth, and at immense speed.

There are many examples of word of a significant event being passed on, not only unofficially but in time for Londoners to make their feelings clear. When Thomas Wolsey left his magnificent home, York Place, for the last time, quietly, unheralded and by water after he lost the King’s favour, he made the unwelcome discovery that hundreds of boatloads of onlookers were on the Thames and on the lookout to see him leave. And at the time of the convening of the hearings at Blackfriars when Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon were due to appear before the Pope’s representative to try the legality of their marriage, it is on record that hundreds of people were there to see and hear.

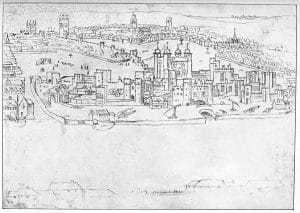

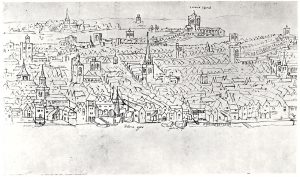

The London of the 1530s was small enough to walk across in half an hour. Covering little more than the present-day Square Mile, it was still largely confined to the old walled area, bounded by the Tower of London in the East, St Paul’s in the West, the River and, approximately, a line from Moorfields to Holborn. It was by far the richest, and, next to the Court, the most influential area in the country. And the official surveillance was every bit as efficient – Thomas Cromwell lived close to what is now the Bank of England, and ran a spy network that included paid listeners in every significant household. For most of the people most of the time, the safest way of staying alive was to keep quiet. And, picking our way through the conflicting evidence of how London greeted its new Queen at Anne Boleyn’s coronation, that is exactly the route the people took, watching the spectacle and drinking the free wine but reserving judgement about the woman riding past them to be crowned.

Lissa Chapman is a theatre director, writer and historian. She is joint founder, with Jay Venn, and artistic director of Clio’s Company, which specialises in researching, writing and staging site-specific theatre, particularly in the London area, and has worked in a wide variety of contexts, from the Tower of London and a variety of cathedrals, stately homes and cathedrals to Kew Gardens and an historic tidal mill, by way of a stretch of canal towpath and the odd damp field. Two productions have been set in the London of Anne Boleyn’s day, and in 2013 the company were chosen to take part in the Lord Mayor’s Show, for which they researched and recreated part of Anne Boleyn’s coronation procession. After walking through London in the pouring rain in the company of eighty nine-year-olds, singing one of the coronation songs for what was probably its first performance since 1533, it was probably inevitable that the research became a book.

Lissa’s book, Anne Boleyn in London

Romantic victim? Ruthless other woman? Innocent pawn? Religious reformer? Fool, flirt and adulteress? Politician? Witch? During her life, Anne Boleyn, Henry VIII’s ill-fated second queen, was internationally famous – or notorious; today, she still attracts passionate adherents and furious detractors.

Romantic victim? Ruthless other woman? Innocent pawn? Religious reformer? Fool, flirt and adulteress? Politician? Witch? During her life, Anne Boleyn, Henry VIII’s ill-fated second queen, was internationally famous – or notorious; today, she still attracts passionate adherents and furious detractors.

It was in London that most of the drama of Anne Boleyn’s life and death was played out – most famously, in the Tower of London, the scene of her coronation celebrations, of her trial and execution, and where her body lies buried. Londoners, like everyone else, clearly had strong feelings about her, and in her few years as a public figure Anne Boleyn was influential as a patron of the arts and of French taste, as the centre of a religious and intellectual circle, and for her purchasing power, both directly and as a leader of fashion. It was primarily to London, beyond the immediate circle of the court, that her carefully ‘spun’ image as queen was directed during the public celebrations surrounding her coronation.

In the centuries since Anne Boleyn’s death, her reputation has expanded to give her an almost mythical status in London, inspiring everything from pub names to music hall songs, and novels to merchandise including pin cushions with removable heads. And now there is a thriving online community surrounding her – there are over fifty Twitter accounts using some version of her name. This book looks at the evidence both for the effect London and its people had on the course of Anne Boleyn’s life and death, and the effects she had, and continues to have, on them.

Hardcover: 248 pages

Publisher: Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1473843618

ISBN-13: 978-1473843615

Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon.com and Amazon UK.