Thank you so much to Sandra Vasoli, author of Je Anne Boleyn: Struck with the Dart of Love for sharing some of her thoughts and research on “The Lady in the Tower” letter. Over to Sandi…

Thank you so much to Sandra Vasoli, author of Je Anne Boleyn: Struck with the Dart of Love for sharing some of her thoughts and research on “The Lady in the Tower” letter. Over to Sandi…

Today, 6 May, marks 479 years since the origination of a compelling and mysterious letter, written according to some by Queen Anne Boleyn to her husband Henry VIII. Ostensibly produced while she was imprisoned in the Tower after having been accused of abominable crimes, the letter is poignant, courageous, noble and masterfully composed.

And for the past 475 years, its authenticity has been hotly debated.

I am captivated by its story. As I researched my second book Je Anne Boleyn: Truth Endures, I became preoccupied with the many tales surrounding this letter. I wondered what it might have meant in the due course of history if it had, in fact, been authored by Anne. And I couldn’t help but consider what Henry’s reaction to it might have been, if he were to have read it. So I determined to discover everything I possibly could about it. I hoped that I might be able to find a clue which had perhaps been previously overlooked, or a series of leads which would indicate its veracity. In the process of searching, I discovered much – enough to cast a bright light on the riddle of the letter; and a shocking, previously overlooked original notation which may change the way we view the tragic story of Anne and Henry.

While watching a tennis match, Queen Anne was interrupted by a messenger on 2 May 1536. He delivered a command that she was to meet members of the King’s Privy Council immediately. Confronted by her uncle, the Duke of Norfolk, and two others, she was charged with adultery – thereby treason – and subsequently arrested and taken as a prisoner to the Tower, where she was closely guarded. Her warden was Sir William Kingston, Constable of the Tower. Kingston had been host to Anne during her stay at the Tower prior to her coronation, so he was familiar to her. She may have taken some small comfort in that knowledge, but it was to serve her no purpose. Kingston was required, along with the women who were assigned as Anne’s sentinels both night and day, to observe, listen, and record any and everything the Queen said and did. These reports were to be delivered to Thomas Cromwell, the King’s Chief Minister.

It was chronicled by Bishop Gilbert Burnet, a mid 17th century antiquarian and a collector and preserver of records and documents, in his The History of the Reformation of the Church of England, that once locked in the Tower, Anne made “deep protestations of her innocence, and begged to see the King, but that was not to be expected.”1 This fact had been recorded by Constable Kingston, in one of five letters he wrote to Cromwell documenting Anne’s captivity; Burnet viewed those letters.

Having been refused the chance to see her husband to try and convince him of her innocence (whether or not Henry would have agreed to see Anne is another question), Anne wavered, over the following days, between deep despair and staunch resolution. It was her great desire to communicate with Henry and it follows naturally that, in the absence of a personal meeting, she would demand the privilege of writing to him. While her jailers may have been able to refuse her an audience, still, Anne was the Queen. It would have been an extraordinary act of defiance to forbid her the right to compose a letter to her husband the King. Yet Kingston was responsible for maintaining control of the desperate situation and was under orders to dispatch all information about her behaviors, her conversations, any single utterance to Cromwell, in anticipation that she would surely incriminate herself. He may not have thought it wise to allow Anne to privately correspond with the King without his knowing (and reporting) exactly what had been said. It makes sense, then, that Anne would have been permitted to dictate a letter, which was written for her either by Kingston himself, one of the ladies in attendance, or a scribe.

The letter’s content is as follows:

“To the King from the Lady in the Tower” [Heading said to have been added by Thomas Cromwell]

Sir, your Grace’s displeasure, and my Imprisonment are Things so strange unto me, as what to Write, or what to Excuse, I am altogether ignorant; whereas you sent unto me (willing me to confess a Truth, and so obtain your Favour) by such a one, whom you know to be my ancient and professed Enemy; I no sooner received the Message by him, than I rightly conceived your Meaning; and if, as you say, confessing Truth indeed may procure my safety, I shall with all Willingness and Duty perform your Command.

But let not your Grace ever imagine that your poor Wife will ever be brought to acknowledge a Fault, where not so much as Thought thereof proceeded. And to speak a truth, never Prince had Wife more Loyal in all Duty, and in all true Affection, than you have found in Anne Boleyn, with which Name and Place could willingly have contented my self, as if God, and your Grace’s Pleasure had been so pleased. Neither did I at any time so far forge my self in my Exaltation, or received Queenship, but that I always looked for such an Alteration as now I find; for the ground of my preferment being on no surer Foundation than your Grace’s Fancy, the least Alteration, I knew, was fit and sufficient to draw that Fancy to some other subject.

You have chosen me, from a low Estate, to be your Queen and Companion, far beyond my Desert or Desire. If then you found me worthy of such Honour, Good your Grace, let not any light Fancy, or bad Counsel of mine Enemies, withdraw your Princely Favour from me; neither let that Stain, that unworthy Stain of a Disloyal Heart towards your good Grace, ever cast so foul a Blot on your most Dutiful Wife, and the Infant Princess your Daughter.

Try me, good King, but let me have a Lawful Trial, and let not my sworn Enemies sit as my Accusers and Judges; yes, let me receive an open Trial, for my Truth shall fear no open shame; then shall you see, either mine Innocency cleared, your Suspicion and Conscience satisfied, the Ignominy and Slander of the World stopped, or my Guilt openly declared. So that whatsoever God or you may determine of me, your Grace may be freed from an open Censure; and mine Offence being so lawfully proved, your Grace is at liberty, both before God and Man, not only to execute worthy Punishment on me as an unlawful Wife, but to follow your Affection already settled on that party, for whose sake I am now as I am, whose Name I could some good while since have pointed unto: Your Grace being not ignorant of my Suspicion therein.

But if you have already determined of me, and that not only my Death, but an Infamous Slander must bring you the enjoying of your desired Happiness; then I desire of God, that he will pardon your great Sin therein, and likewise mine Enemies, the Instruments thereof; that he will not call you to a strict Account for your unprincely and cruel usage of me, at his General Judgement-Seat, where both you and my self must shortly appear, and in whose Judgement, I doubt not, (whatsover the World may think of me) mine Innocence shall be openly known, and sufficiently cleared.

My last and only Request shall be, That my self may only bear the Burthen of your Grace’s Displeasure, and that it may not touch the Innocent Souls of those poor Gentlemen, who (as I understand) are likewise in strait Imprisonment for my sake. If ever I have found favour in your Sight; if ever the Name of Anne Boleyn hath been pleasing to your Ears, then let me obtain this Request; and I will so leave to trouble your Grace any further, with mine earnest Prayers to the Trinity to have your Grace in his good keeping, and to direct you in all your Actions.

Your most Loyal and ever Faithful Wife, Anne Bullen.

From my doleful Prison the Tower, this 6th of May.

Upon reading this missive, one is struck by its tenor of familiarity; that which, even in the direst of circumstances, is emblematic of the close relationship between husband and wife. Her opening line… “Sir, Your Grace’s Displeasure and my Imprisonment are things so strange unto me, as what to write, or what to excuse, I am altogether ignorant” is reminiscent of arguments known to couples throughout the ages. She then chastises him for allowing her to be confronted by her uncle, Norfolk, who by that time was her open enemy (and had a great deal to do with the construction of the plot against her). In the second paragraph she delivers a blow by telling him she is well aware that his “Fancy” has turned to “some other subject.” But she then carefully expresses her humility, telling him she is well aware that he raised her from “a low estate”. She pointedly refers to herself as “Anne Boleyn, with which name and place I could willingly have contented myself…”

Further on, Anne is true to the piquant nature for which she was well known. She tells him that if he has already decided of her that she is guilty of his “Infamous Slander”, and that her death will “bring you the enjoying of your desired happiness”, then she hopes for Henry’s sake that God will pardon him for his “unprincely and cruel usage”, for, as she reminds him – they will both shortly appear before God and be subject to His judgement. She adds the final jolt: she is confident God will know her to be innocent and she will be sufficiently cleared. Her implication is strong: as for Henry? She worries for the salvation of his eternal soul due to his Great Sin.

Anne then agonizes for the men she knows have been unjustly imprisoned on her behalf. In this paragraph one can feel her anguish: she begs Henry to be lenient with them if ever he loved her, just as a woman would do when imploring a man with whom she had been intimate. Finally, she ends by reminding him – not that she is Queen – but that she is simply his loyal and ever faithful wife, Anne Boleyn.

The provenance of the letter is convoluted. Numerous early historians have included references to it in their collections, or treatises about the history of England. These include Lord Herbert of Cherbury (1583-1648), John Strype (1643 – 1737), Gilbert Burnet (1643 – 1715), Bishop White Kennett (1660 – 1728), Sir Henry Ellis (1777 – 1869), Agnes Strickland (1796 – 1874), and James Froude (1818 – 1894). Only a few of these state that they actually saw the letter which they considered to be the ‘original’. It is reported by the earliest historians that the letter was “said to be found among the papers of Cromwell then Secretary”.2 Anne’s letter, according to the accounts of several of these historians, was found along with the five letters Kingston had written to Cromwell, in his personal papers some time after his own beheading in 1540 at the hands of Henry.

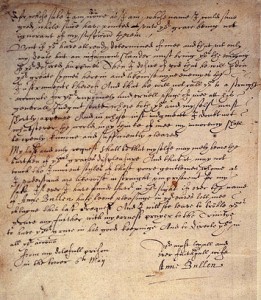

There are several early versions of the letter extant. What makes this mystery even more difficult to solve is the fact that none of them, though all are written in an early (16th century) script, appear to be in handwriting identifiable as Anne’s. Therefore when one refers to the ‘original’ letter: the one which was found in the deceased Cromwell’s belongings, it is, in fact, a transcription and not a document actually penned by Anne. My research leads me to firmly believe that this letter, which was kept by Thomas Cromwell along with the other records of Anne’s imprisonment, was scribed. That, for some specific reason, it was written by someone other than Anne, while being dictated by Anne herself. This document – the scribed letter, the one which was in Cromwell’s papers – is held carefully at the British Library in the Cotton Manuscripts. It now remains as just a portion of the original, the sides having been scorched and burned away in a fire at the Ashburnam House Library in 1731, where this document, among many others, was being stored. So after 1731, only a part of this particular letter would have been readable.

Prior to 1731, then, at least two copies were made of the complete, scribed, original letter. One is headed with the words ‘Queen Anne Bullen to King Henry the 8 found among T. Cromwells papers’ (the one in the photo above). The other copy exists in an ancient volume in the British Library: ‘Collection of Letters of Noble Personages’, which is part of the Stowe manuscripts. This copy was almost certainly written by an enigmatic figure in London in the early 1600s, known only as The Feathery Scribe. This scrivener transcribed hundreds of documents, thousands of words, for such patrons as Sir Robert Cotton, Sir Francis Bacon, John Donne, Henry King, the Earl of Leicester, William Lord Burghley, and John Fisher. The Stowe collection containing this version of the letter was completed prior to 1628,3 making it the earliest known reproduction of the ‘original’.

My forthcoming book Anne Boleyn’s Letter from the Tower will detail all of my findings along with images of the early copies of the letter. There are intriguing questions to consider: who was first to find the letters – Kingston’s and Anne’s – in Cromwell’s private papers after his death? And why was Anne’s with Kingston’s? Why did Cromwell keep it? It seems obvious that it was never delivered to Henry, else why would it have remained in his possession? What would Henry’s reaction to it have been had he read it? Might it have swayed him? We will never know. What evidence can be pieced together today to demonstrate convincingly that Anne authored this composition, and what facts refute claims by some historians that it is a forgery?

The implications of the genuineness of such a heartrending, personal letter, and the fact that it never reached its intended reader, are actually quite dramatic as one considers Anne’s cruel fate. Read the details resulting from exhaustive research in my book early this summer, and learn why I believe without any doubt that Anne’s appeal to Henry is completely authentic.

Coupled with the text of such a heartbreaking letter is a finding which left me completely astounded. In the course of my search I uncovered a contemporary notation within the Stowe collection of manuscripts which refers to Henry’s great grief, on his deathbed, for his fatal decision concerning Anne. The legitimacy of this notation is certain: its significance is stunning. I will provide the complete text, along with an image of the notation, and a discussion of its interpretation in the Nutshell series book.

These recordings, expressed by two people whose entwined lives had such a profound fate, add to the pathos of events which haunt us today, almost five centuries since their occurrence.

Click here to read Sandi’s article about her visit to the Vatican archives to see Henry VIII’s love letters to Anne Boleyn.

Sandra Vasoli earned a bachelor’s degree in English and biology from Villanova University before embarking on a thirty-five-year career in human resources for a large international company.

Sandra Vasoli earned a bachelor’s degree in English and biology from Villanova University before embarking on a thirty-five-year career in human resources for a large international company.

Having written essays, stories, and articles all her life, Vasoli was prompted by her overwhelming fascination with the Tudor dynasty to try her hand at writing fiction. While researching what would eventually become her Je Anne Boleyn series, Vasoli was granted access to the Papal Library. There she was able to read the original love letters from Henry VIII to Anne Boleyn—an event that contributed greatly to the creation of her fictional memoir.

Vasoli currently lives in Gwynedd Valley, Pennsylvania, with her husband and two greyhounds. She is currently working on Je Anne Boleyn: Truth Endures and Anne Boleyn’s Tower Letter: In a Nutshell which will be published by MadeGlobal Publishing.

Notes

- The History of the Reformation of the Church of England, Gilbert Burnet, Vol I Book III, p 198.

- Lord Herbert of Cherbury; The Life and Raigne of King Henry the Eighth; 1649; Thomas Whitaker, London; p 382.

- http://www.celm-ms.org.uk/repositories/british-library-stowe.html

Sources

- British Library Catalogue of English Manuscripts http://www.celm-ms.org.uk/

- British Library Cotton MS Otho CX fol. 232r

- British Library Stowe MS 151

- British Library Lansdowne MS 979

- Burnet, Gilbert; The Historie of the Reformation of the Church of England; Richard Chiswell, London

- Ives, Eric; The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn; Blackwell Publishing; 2004

- Lord Herbert of Cherbury; The Life and Raigne of King Henry the Eighth; 1649; Thomas Whitaker, London

- Ridgway, Claire; The Fall of Anne Boleyn; MadeGlobal Publishing; 2012

- Weir, Alison; The Lady in the Tower; Ballantine Books; 2010

good analysis. The fact that both extant copies are not original also makes it impossible to analyze both handwritings that would have been on it, both Anne’s and Cromwell’s.

The only thing I would caution is staring that the reference in the beginning to her ancient enemy is Norfolk. The writing does not name names. Better to say I believe that the Lester writer means Norfolk, rather than making it a statement of fact. She had a lot of enemies and that part does not necessarily refer to the council meeting on the 2nd.

Excellent Sandra! Your research and my fiction in the upcoming story of Anne Boleyn’s last hour, Phoenix Rising, have many similarities. I look forward to reading your In A Nutshell story.

Excellent article! I am looking forward to reading your upcoming book on this letter. Please let us all know when it becomes available for purchase.

Thank you everyone! Notice of upcoming book`s publication will be posted on the Anne Boleyn Files and my Facebook page, Je Anne Boleyn.

All of your comments are very thoughtful. With regard to Death Rock Me Asleep…I have found it to an unbearably sad yet beautiful composition. Did Anne write it? In truth,I don’t know. I have not researched its provenance. On the other hand, I have spent 8 months just studying the `tower letter` and I have seen the early copies in the originals at the British Library. I have studied thoroughly what all of the historians, including Eric Ives, have said about this letter. I do not think anyone has spent more focused study on it than I have. And my conclusions are without doubt that she authored it. That she purposely referred to herself as Anne Boleyn, his loyal and faithful wife, because that was what was important in that moment. Not that she was Queen. I distinctly believe that Cromwell never gave the letter to Henry, because he feared that it may have caused Henry to reconsider his decision.

Anne felt it her right to state what she did to her husband because of the intense intimacy they had shared for some years. He had loved her to distraction, that was clear from his letters to her. And she believed that he very well might be testing her, and might rescue her. For all these reasons, and more, I believe this was Anne’s chance to speak to her husband. Would it have made a difference had he seen it? We just don’t know.

Dear Sandra,

I am a recent member of the Anne Boleyn Files and after reading the letter, I thought it very touching. It shows that she did indeed still love Henry, even when she knew that she was to be executed very shortly. Her pleading for her life to Henry in such loving and tender words, even for those who also had been arrested, shows her depth of love and humility for others as well. What I have read thus far about my ancestor, makes me truly believe she was innocent. Thank you for all of your research you accomplished.

Has it been considered that Cromwell would have authorised a copy of Ann boleyn’s original letter to Henry to keep in his own records? This is why the letter in an unfamiliar hand was found in his papers, together with those from Kingston. Henry may well have been passed the original and torn or screwed it up without reading it, such was his anger and humiliation at the charges Cromwell had shown him concerning Ann’s behaviour. What we see now retained is only a copy made by one of Cromwell’s servants perhaps at his instruction before passing the original to Henry.

I have no doubt Henry was not as black as he was painted but had all the turmoil of a sensitive man who was also trying to be a strong and respected King. He frequently over egged it both in terms of affection and anger but he was very much the victim of strong emotions. I am sure once he had rationalised his thoughts as time passed, he must have looked back on the years when he had longedfor Ann and made her his queen, and at Elizabeth their daughter, and regretted his hasty actions. He could hardly admit it publicly and still appear consistent, as a king should, which perhaps explains his death bed expressions of guilt.

Has it been considered that Cromwell would have authorised a copy of Ann boleyn’s original letter to Henry to keep in his own records? This is why the letter in an unfamiliar hand was found in his papers, together with those from Kingston. Henry may well have been passed the original and torn or screwed it up without reading it, such was his anger and humiliation at the charges Cromwell had shown him concerning Ann’s behaviour. What we see now retained is only a copy made by one of Cromwell’s servants perhaps at his instruction before passing the original to Henry.

I have no doubt Henry was not as black as he was painted but had all the turmoil of a sensitive man who was also trying to be a strong and respected King. He frequently over egged it both in terms of affection and anger but he was very much the victim of strong emotions. I am sure once he had rationalised his thoughts as time passed, he must have looked back on the years when he had longedfor Ann and made her his queen, and at Elizabeth their daughter, and regretted his hasty actions. He could hardly admit it publicly and still appear consistent, as a king should, which perhaps explains his death bed expressions of guilt.

I have always believed the letter to be authentic. Either it was dictated by Anne then or Cromwell copied the original to keep for his record. It is so personal and honest and so very Anne, based on all that I have read about her character. I look forward to reading your work.

I, too, have always believed in my heart that the letter was real. It is very much within what I consider Anne’s character–it’s brave, a little saucy, intimate and very much an effort to rekindle kind feelings in her husband. I don’t believe he ever read it–becuae I think he would have been moved by it if he had done so, perhaps to the point of changing history, who knows? Thanks for a great article!

Thank you for the insight on the letter . It certainly has a ring of truth to it. Why would Anne not attempt to write to her husband as letters were such an important part of their relationship. I wonder what Sandi thinks about the poem

O Death, O Death, rock me asleepe. Written by Anne??

Great article Sandi. Makes me proud to be a Pennsylvanian!

Claire, I just reread one of your earlier posts in which you state your belief the letter is a forgery. Now that you’ve heard Sandi’s argument, do you still feel the same way?

I doubt that this letter is genuine it’s nice to think that Anne had written this letter but I believe that she wasn’t allowed to write to Henry anyway, she was a convicted traitor even tho we think she was innocent, and I don’t think anyone would have had the nerve to have delivered it to the King also she would have signed it from Anne The Queen or Anne R , her correct title, not the Lady In The Tower, this makes me think it’s a forgery she is said to have composed the song O Death Rock Me Asleep but there’s doubts over that to, she mentions Henrys great sin in the letter and I don’t think she would have written that, the contents are a bit over bold and whilst we know Anne was incredibly brave this was a woman who had to tread very warily, she was in the Tower under sentence of death so no I don’t believe this letter was written by her, I think had she been allowed to send Henry a letter she would have worded it very differently, but I don’t believe she would have been allowed the luxury of writing to him anyway.

She was a convicted traitor, yes. But not by any means was she a common prisoner: She was a queen, and she didn’t go into the dungeon, she stayed at her lodging. Anne was always a bold woman, even when she knew that it would be unfavorable.

“As to the letter’s bold attitude toward Henry, this was characteristic of Anne, and (as she acknowledged in her trial speech) she was aware that it overstepped the borders of what was acceptable. Her refusal to contain herself safely within those borders was what had drawn Henry to her; she could not simply turn the switch off when it began to get her in trouble. To do that would have been to relinquish the only thing left to her at this point: her selfhood. Ives says that it would “appear to be wholly improbable” for a Tudor prisoner to warn the king that he is in imminent danger from the judgment of God.” But Anne was no ordinary prisoner; she had shared Henry’s bed, advised and conspired with him in the divorce strategies, debated theology with him, given birth to his daughter, protested against his infidelities, dared to challenge Cromwell’s use of confiscated monastery money. Arguably, it was her failure to be “appropriate” that contributed to her downfall. Now, condemned to death by her own husband, to stop “being Anne” would have been to shatter the one constancy left in the terrible “strangeness” of her situation.”

https://thecreationofanneboleyn.wordpress.com/2014/05/05/an-argument-for-the-authenticity-of-annes-may-6th-letter-to-henry/

Another point I’d like to add is that had the letter been genuine Cromwell would have destroyed it, he wouldn’t have allowed Anne any contact with Henry that would have been a dangerous move, he could have faltered in his resolve to have her executed, don’t forget everything she said and did was reported back to Cromwell by Kingston and it would have been impossible to have smuggled a secret letter out to Henry if they didn’t want Cromwell to see it first, after Catherine Howard was kept under house arrest she wasn’t allowed to see Henry or write to him either, hence her desperate attempt to plead with him when he was in the chapel at Hampton Court, if you consider all these factors it makes it very improbable that the letter was written by Anne, several historians doubt it’s authenticity to, there are only a few letters from Anne that have survived and I doubt this is one of them, as I said in my previous post it’s a nice idea but smacks a bit of romantic fantasy.

Anne was not a convicted traitor before the trial when she wrote the letter (if she indeed wrote it) even if Henry evidently thought that she was guilty and the trial was a mere formality.

However, even traitors had a right to plead for mercy from the king. It was his right to decide whether he would read the letter or not.

When later in the Tower, Cromwell himself to Henry a letter (not the one he was asked to write about Anne of Cleves) where are traits that are similar with Anne’s alleged letter.

I agree with you. Her speech on the scaffold was careful not to criticise Henry and in fact, praised him. I think Anne was very conscious of the welfare of those she left behind (Elizabeth and the Careys) to criticise Henry so explicitly. I also think she would probably have known that sending him such a letter would make him more angry rather than save her skin. After all, this was a woman who had seen years and years of begging and pleading from Catherine of Aragon to no avail.

I also agree that Cromwell would have destroyed the letter. It was too dangerous for him to have. Henry and Anne’s relationship was said to be ‘sunshine and storms’ and Cromwell couldn’t take the smallest risk they would reconcile, his life depended on it. If Henry had taken Anne back he would certainly have been executed for promoting the allegations against her. Ditto if Henry had any regrets.

Also the timing of it’s apparent reemergence after Elizabeth’s death seems rather too convenient. And you can never say for certain that a letter from that period was scribed, it’s impossible to know if it came from someone else’s mouth or the writers mind. Just because a writer took dictation sometimes doesn’t mean they did every time they wrote something.

This is assuming Henry didn’t know anything about Cromwell’s plot, which I don’t believe at all. Her speech on the scaffold was like any other speech before an execution, praising the king and asking everyone to pray for him were etiquette.

By the time the letter was written, Anne also might still have hoped to convince the king. After the trial and before her execution these hopes dwindled, so it makes sense that besides following etiquette, she’d also try to placate Henry for Elizabeth’s sake.

I have always believed the letter to be authentic. It just screamed “Anne Boleyn” to me the first time I laid eyes on it. I do acknowledge the arguments against the letter’s authenticity, but in my opinion, a lot of them actually are, at least in part, refutable. Susan Bordo (as well as this article) makes some excellent points I wholeheartedly agree with.

Very insightful analysis of the letter! I do agree it is authentic, and think that Cromwell hung on to it, with the hope that he could find something in it that he could use to further incriminate her. Can’t wait to read your book with even more details!

I remember reading once in an old novel that Henry VIII, when dying, called out Anne’s name along with the more famous claim of “monks, monks, monks…” Granted, it is portrayed as a bit of semi-morbid gossip (“…and that’s the first time he’s mentioned her name since…”–Kat Ashley), but if true, I have a new book to add to my list.

And a comment about the poem–I have seen it (and I couldn’t tell you where exactly) attributed to Anne *or* George Boleyn.

Thanks again to all who read the article and offered such great comments. I would like to mention that I agree with Selina in that Anne was not any prisoner. She remained, at that date, Queen of England, and Henry remained her husband. Of course she would be desperate to communicate with him, and it would have been folly to refuse her that privilege. As to the comment about Cromwell destroying the letter…a document from the Queen to the King? Let’s not forget that this man was a lawyer, and a very smart one. Lawyers don’t destroy documents. My belief is that he just tucked it away… never to be found till after his death.

I believe Ann’s transcribed letter to Henry is authentic.

Sandi – I am curious if you have investigated this POSSIBLE SCENARIO…

Ann’s letter was indeed transcribed for her – dictated from her very lips while imprisoned in the tower, as a last ditch attempt to vindicate herself to her husband. She possibly had no other opportunity to do so.

And then perhaps, it was give to Kingston or Cromwell, but in any case ended up in Cromwell’s papers – and perhaps copies written — not to be found until after all of their deaths???? Perhaps INSTEAD — HENRY FOUND IT OR WAS GIVEN THE LETTER TO READ **AFTER** CROMWELL’S DEATH — BUT WHILE HENRY WAS STILL ALIVE?

That would explain Kingston’s letters (surely given to the King by Cromwell) being found WITH Ann’s. Because they were in HENRY’s stash, not Cromwell’s…or they were Cromwell’s papers found by Henry or a third party who directed them to Henry, when Cromwell died but before Henry’s death. … Hence, Henry took to his grave a horrifying remorseful guilt to the greatest extent possible. Then at the time of his death, he perhaps succumbed to the letter’s very content — he had to face his creator with his sin – just as Ann spoke of in her letter, so he cried out.

Any fact to dispute this scenario or anything supporting it?

p.s. This part is a bit of a reach, but perhaps the above scenario explains why Henry requested to be buried by Jane. I’m not sure he had the energy or time to fall as in love with Jane as he was with Ann. And not so sure the sole fact that Jane bore his son was enough for him to request to be with her for eternity. Buried next to Jane was perhaps the closest way he could spend eternity with Ann, without reneging his public image.

But In the letter allegedly written by her Anne mentions ‘his great sin heirin’ she was in a very dangerous position , there were five other men imprisoned with her, she had to appeal to his sense of justice, his conscience, placating and complete submission were the key here, we know she wasn’t any ordinary prisoner she was Queen but only by marriage to the King, she and five others were at his mercy I think she was too intelligent to have written a comment like that, her sarcasm and barbed remarks were all very well when Henry was besotted with her but now she was a prisoner in the Tower and many never came out of that place alive, she would have had time to compose herself and think through what it was she wanted to say, personally I just think she would have been more careful had she written any letter to him, she didn’t want to enrage him further, that’s just my opinion.

To Christine

Anne was indeed intelligent, yet she was unable to change when she became Queen. Perhaps she saw that the change meant losing her her self.

In the Tower her best chance was to confess everything but present herself a victim and the men as the real guilty ones and throw herself to Henry’s mercy. She did not do it unlike Catherine Howard because it was against her character.

In this, if nothing else, Anne and Cromwell were alike.

John Schonfield writes in his biography of Cromwell’s letter to Henry from the Tower: “he also called the charges against him a pack of lies, invoking God Almighty and the Day of Judgment as his witness. This is not the spirit that Henry expected from his prisoners. Neither is it the air of a man possessed by fear. Had Cromwell been in state of terror, he would have confessed everything.”

I’m afraid nothing will ever convince me this letter is authentic. It’s the tone for me; it sounds late Elizabethan or so, like someone wanted to fill in a gap.

I also have difficulty in believing that the letter is genuine. Anne knew, none better (because she was taking the blame for it) how savagely Henry turned on one of his daughters; I don’t want to believe that Anne would have exposed Elizabeth to the same danger. However, I look forward to reading the “Nutshell” book.

I wrote a post on here last year saying when I read the letter it sound like something Anne would have written as it fits in with what has been recorded about her personality and exchanges with Henry. She sounds exactly like someone who needs to be “right” rather than watching what she says, and keeping the peace (I lie that about her) which was fine when she was withholding her favors, but loses power over time; many a woman has been wooed one way and post marriage been treated another,

Not sure how you get a whole book out of this, but there is certainly enough previous interpretative content out there to peruse prior. I think she wrote it. Look forward to hearing more about “Nutshell” when published.

I believe that the letter is genuine, and I also feel sorry for Anne as she clearly believes that she will get a fair trial and can appeal to his mercy and their years together as man and wife. We don’t have many letters from Anne to Henry; let’s not take this one from her. A wonderful article, thank-you.

I was wondering about the validation of the letter . Are you saying that it cannot be verified to be Anne Boleyn ‘s handwriting ? Or is it Anne ‘s handwriting written in a dictated form ? Was the letter that Anne wrote to Henry a rough draft ?

I truly believe that love existed in the lives of Henry VIII and Anne . Will we ever know if it was the king or kingdom that commanded ” off with her head ! “

I hope my last post was not to graphic or unpolite . I believe everyone at this site holds a deep respect for Queen Anne .

Hello Star, I just saw your recent post. You certainly were not impolite… just asked some really good questions. These were questions I asked myself as I dug deeper and deeper into the letter’s past, and read what historians have said about it over the years. I hope you read my book which is out next week (Anne Boleyn’s Letter from the Tower). It will help to answer some of your questions… at least what I have come to strongly believe after months of study. But basically, yes I am saying that the actual handwriting of the ‘original’ letter is not Anne’s. That is quite certain, even without the aid of a handwriting expert. What I do believe, 100%, is that the words are Anne’s. So then the question becomes… did she dictate the words? Did she do ‘rough copies’ and then had them transcribed for her? These are very plausible options. I describe my reasons in the book for why I believe she didn’t actually scribe the letter.

I, too believe that there was a very deep and emotional love between Anne and Henry. Some couples’ passions are too big to be contained. To me, this was Anne and Henry.

I believe it was from Anne and dictated to someone else to write on her behalf.

I was at Hever Castle last week and saw her signature there. I was impressed with the tapestry of Mary Rose Tudors marriage to the 52 year old King Louis with Anne standing behind Mary Rose Tudor.