On this day in history, 18th June 1546, Anne Askew was arraigned at London’s Guildhall for heresy, along with Nicholas Shaxton, Nicholas White and John Hadlam (Adlams or Adams). She was sentenced to be burned at the stake. Chronicler Charles Wriothesley records this event:

On this day in history, 18th June 1546, Anne Askew was arraigned at London’s Guildhall for heresy, along with Nicholas Shaxton, Nicholas White and John Hadlam (Adlams or Adams). She was sentenced to be burned at the stake. Chronicler Charles Wriothesley records this event:

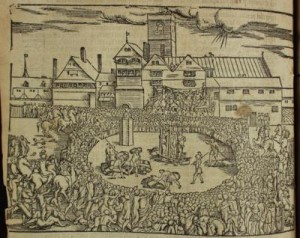

“The eigh tenth daie of June, 1546, were arraigned at the Guilde Certaine Hall, for heresee, Doctor Nicholas Shaxston, sometyme bishop of arraigned for Salisburie; Nicholas White, of London, gentleman; Anne Kerne[Kyme], alias Anne Askewe, gentlewoman, and wiffe of Thomas Kerne [Kyme], gentleman, of Lyncolneshire ; and John Hadlam, a of Essex, taylor ; and were this daie first indited of heresie and after arraygned on the same, and their confessed their heresies against the sacrament of the alter without any triall of a jurie, and so had judgment to be brent[burnt].”

You can read more about Anne in my article Anne Askew Sentenced to Death.

Notes and Sources

- A Chronicle of England during the reigns of the Tudors, from A.D. 1485 to 1559, Charles Wriothesley, p167

This another trajic event for this women and all others,how was it that they were being cahrge with heresy,and they were not given fair trial?This seems to have been going on for so long,although there laws much different then todays,it just unfair not given a proper trail.It’s always been church and state,and still is today ,but we don’t run around burnnig one at the stake,the civals at any rate,we do know they practice that in some parts of the world,we know were that is.My prayers are with all that diedsuch a cruel needless trajic death.Baroness

Anne Askew was an incredible, brave, intellegent woman who deserves to be better known. She knew that she would be risking death by preaching the gospel but didn’t stop doing what she thought was right. She is still an example to us all. God bless her soul.

Let us not forget the men who were treated the same way, and indicted and without trial. I find this horrendous; however, “One important point to note is that the Act effectively made it treasonable to support the authority of the Pope over the Church of England. By tying the church and monarch so closely together, support for Catholicism became not simply a statement of personal religious conviction, but a repudiation of the authority of the monarch, and as such, an act of treason punishable by death.”

http://www.britainexpress.com/History/tudor/act-of-supremacy.htm (and this is basic, but it gives the gist of what happened.

There were, of course, exceptions to this, but after “The Act of Supremacy” was passed in 1534, the Act was made for a reason, and that was that the Henry came to the conclusion (with advisors, I’m almost sure), that, under the thinking that made this Act was, that the people could not serve both the Pope and King at the same time. The King was made Head of the Church of England, and was very important, as it made England free from Rome, justified his marriage to Queen Anne, so the “Great Divorce” was virtually ended. With the dissolution of the monestaries and nunneries beginning in 1534, led by Cromwell, anyone not obeying this Act and not submitting it was subject to this horrible kind of punishment. Perhaps a lot for an example to those who did not wish to comply. This was an horrible event, but those chosen were not just the women, but the men involved as well. No one was an exception.

I do feel of Anne Askew, and I read more about her in the article that follows yesterday, but as a comment, on just the surface in this introduction is to get to the article which is excellent.

Thank you, WilesWales

Are there biographies or novels written about Anne Askew?

Mary,I am sure that there are books mostly history,when I want to find out on just about anything,I go to the EnglishArcives.com or the Veinna Arcives.com. Also if you type in her name or any one you want to learn about just go on line you can also buy Claires books there really both good reads and Facs not fics, becarefull on the books you by as some have way to much fiction and not what really happen. Kind Regards Baroness

Thank you for the information Baroness. I will try the sites you mention. I have both of Claire’s books – wonderful!

Hi Mary,

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography have an excellent article on Anne and the writer, Diane Watt, lists the following sources:

“Sources The examinations of Anne Askew, ed. E. V. Beilin (1996) · C. Wriothesley, A chronicle of England during the reigns of the Tudors from AD 1485 to 1559, ed. W. D. Hamilton, 1, CS, new ser., 11 (1875) · J. G. Nichols, ed., Narratives of the days of the Reformation, CS, old ser., 77 (1859) · D. Watt, ‘Serpents and doves: Anne Askew and Foxe’s godly women’, Secretaries of God: women prophets in later medieval and early modern England (1997), 81–117 · E. V. Beilin, ‘Anne Askew’s self-portrait in the Examinations’, Silent but for the word: Tudor women as patrons, translators, and writers of religious works, ed. M. P. Hannay (1985), 77–91 · E. V. Beilin, ‘A challenge to authority: Anne Askew’, Redeeming Eve: women writers of the English Renaissance (1987), 29–47 · E. V. Beilin, ‘Anne Askew’s dialogue with authority’, Contending kingdoms: historical, psychological, and feminist approaches to the literature of sixteenth-century England and France, ed. M. R. Logan and P. L. Rudnytsky (1991), 313–22 · P. McQuade, ‘“Except that they had offended the lawe”: gender and jurisprudence in The examinations of Anne Askew’, Literature and History, 3rd ser., 3/2 (1994), 1–14 · L. P. Fairfield, ‘John Bale and the development of protestant hagiography in England’, Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 24 (1973), 145–60 · J. N. King, English Reformation literature: the Tudor origins of the protestant tradition (1982) · S. Brigden, London and the Reformation (1989) · J. R. Knott, ‘Heroic suffering’, Discourses of martyrdom in English literature, 1563–1694 (1993), 33–83 · B. Makin, ‘An essay to revive the ancient education of gentlewomen’, The female spectator: English women writers before 1800, ed. M. R. Mahl and H. Koon (1977) · J. K. McConica, English humanists and Reformation politics under Henry VIII and Edward VI (1965) · D. MacCullough, Thomas Cranmer (1996) · D. Starkey, The reign of Henry VIII: personalities and politics [new edn] (1991) · M. Huggarde, The displaying of the protestantes (1556) · R. Crowley, The confutations of Nicholas Shaxton (1548) · J. G. Nichols, ed., The chronicle of the grey friars of London, CS, 53 (1852) · LP Henry VIII, 21/1, no. 898 · E. Ayscu, A historie contayning the warres, treaties, marriages betweene England and Scotland (1607) · City of London RO, Repertory 11, fol. 174v · GL, MS 9531/12, fol. 109 · A. R. Maddison, ed., Lincolnshire pedigrees, 1, Harleian Society, 50 (1902) · HoP, Commons, 1509–58, 1.342–3 · E. Mazzola, ‘Expert witnesses and secret subjects: Anne Askew’s Examinations and Renaissance self-incrimination’, Political rhetoric, power, and Renaissance women, ed. C. Levin and P. A. Sullivan (1995), 157–71 · T. Betteridge, ‘Anne Askewe, John Bale, and protestant history’, Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, 27 (1997), 265–84”

Diane Watt has also written a book Secretaries of God: Women Prophets in Late Medieval and Early Modern England (Library of Medieval Women), in which she writes about women like Anne Askew and Elizabeth Barton (the Holy Maid of Kent).

I hope that helps!

Hi Claire

Thank you so much for all the sources on Anne Askew. I will have a great time checking them out. May I say that I have never come across such a well thought out and informative site on Tudor times. For years now I have been reading about the principal figures – Henry, his wives and children, both biography and fiction, starting in my teens with Jean Plaidy. At this stage, I would like to know more about the men and women in the wings, such as Anne Askew and Elizabeth Barton – such brave women who spoke out when it was so dangerous to do so. Thank you also for your books which gave the facts in such a clear and readable way.

Hi Mary,

Thank you, that’s so kind of you to say. I know exactly what you mean, I want to research Katherine Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk, a bit more as she seems a fascinating character too.

Wow Claire! You rock! I thank you so very much as well. No fiction in you list, I’m quite certain. I know if my library doesn’t have it, then interlibary loan helps a great deal! Thank you, again, WilesWales

I don’t think you can compare Elizabeth Barton with Anne Askew. Anne preached the gospel, read the bible in English and openly stated her religious beliefs even though she knew the consequences. Elizabeth Barton by contrast claimed to have visions. which warned Henry of dire consequences if he married Anne Boleyn. She started this before the split with Rome so her intent was political not religous. She also confessed that they had all been fake.

Luckily, in the case of Anne Askew we can read her own account of her examinations, as they were smuggled out of the country after her death. This gives a great insight into her character, but in the case of Elizabeth Barton we have nothing but the views of her detractors. When her visions and prophesies were in keeping with Henry’s views she seems to have been credible to him, having had meetings with both him and Wolsey. She may have been crazy, we don’t know, but she had the courage to speak out for what she believed to be true.

It is possible that Elizabeth was an epileptic. It could be that she made up her visions because otherwise people would have thought she was possesed by the devil. I feel sorry for her because it seems that she was lead on and used by other people for their own ends.